In early December last year, I found myself holding an old photograph of a group of booksellers, seated at an event, posing with a famous author. The photograph was from 1902. The author was Mark Twain. In the box were more photos: storefronts of long-gone famous bookstores, booksellers deep in conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr., booksellers standing in the Oval Office with various presidents, photographs of some of my mentors and book folk whom I admired, looking as young as I was when I met them.

In early December last year, I found myself holding an old photograph of a group of booksellers, seated at an event, posing with a famous author. The photograph was from 1902. The author was Mark Twain. In the box were more photos: storefronts of long-gone famous bookstores, booksellers deep in conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr., booksellers standing in the Oval Office with various presidents, photographs of some of my mentors and book folk whom I admired, looking as young as I was when I met them.

Earlier, at the Heartland Fall Forum trade show, I ran into Allison Hill, CEO of the American Booksellers Association. I asked her if I could plan a visit to the ABA offices in White Plains, N.Y., to do some research in the ABA Archives for a book I am writing. She said normally I would be welcome, but that request would be complicated as the ABA was not renewing their lease in February. Everything in the office, including the archive, needed to find a new home. Allison also expressed uncertainty on where that home would be. I told her I had an idea.

Last summer, I traveled to the University of Reading, west of London, to attend the Second Annual Bookselling Research Network Conference in association with the Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing. I had the pleasure to meet some scholars who are focusing on various aspects of bookselling and bookstores. A common theme in every conversation was how difficult it was to find primary sources on historical bookstores. It is rare for a retail bookstore to consider that their papers and ephemera might have historical value and donate them to a library archive. One researcher was fortunate to find that the bookstore she was researching had just thrown more than 40 years of files and ephemera in their basement. She compared her experience with an archeological dig.

After my conversation with Allison, I reached out to my new friends and asked them to connect me to any acquisitions librarian who might be interested in housing the ABA Archive. The response was swift--many institutions responded immediately and enthusiastically. Choosing one was difficult, but the Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library was the perfect fit. They were also in New York and have a world-renowned reputation for their collection on the history of the book.

I traveled to ABA headquarters in White Plains to help stage all the materials for the head archivist. I can't understate how profound and mind-blowing it was to look through these materials. Stacked in a small, empty office were about 60 boxes of materials that told the story of bookselling in America over the past 125 years. I saw every original publication of the ABA Bulletin, a newsletter sent to bookstores from 1917 to the late '50s, then sporadically after that until the 1970s. There was a photograph of all booksellers that attended every annual convention from 1902 to 1958. Someone had meticulously put together scrapbooks from all the years of the National Book Awards--the precursor to today's NBA in which booksellers voted and chose the best books of the year. I found 16mm films, VHS tapes, CD-ROMs, cassette tapes, slides--all of which I could barely determine what treasures lay within.

As I sorted, photographed, and scanned, I felt a profound sense of connection to these past booksellers. I was witnessing their struggles for fair pricing on books; the intense competition with the subscription book clubs, then department stores, then chain stores. Their conversations on ways to get customers in the store, to get people in the habit of reading, were intimately familiar. In the notes and documents, there were heated debates over policies, legal battles, forgotten great ideas, and celebrations. Their struggles and their successes mirrored my experiences as a bookseller.

On the surface, it all seemed business-focused. Yet between fighting for market share and against unfair business practices, marketing campaigns to get more readers and sell more books, and various initiatives designed to support independent bookstores was the underpinning that the job of getting books into reader's hands was important, even essential. This was a community of people who all wanted to keep the flow of ideas free of censorship, give authors a fair chance to inform, entertain, and inspire, keep their communities literate, and ensure a next generation of booksellers continued their work (while hopefully making a modest living).

The ABA Archive will eventually be available to the public to explore. Now that the ABA and Columbia have a connection, any new materials that contribute to this story can be added to the collection in perpetuity. The ABA celebrates its 125th anniversary next year. Someday 125 years from now, a curious bookseller will be able to see everything we are doing today to connect books, readers, and their own communities. They will know that they are a part of a long tradition of people who believed in the power of books to act as a cultural and political expression, to create community, and connect us all to something bigger than ourselves.

With the encouragement of the ABA, I am launching the Bookseller Oral History Project at Winter Institute in Cincinnati. Intended to collect the experiences, insights, and perspectives of current and former booksellers, the recording and interviews will preserve the voices of booksellers so that someday that same future bookseller can hear our story from the primary source. This project is currently self-funded. With the same passion that I sell books, now I am also working to preserve the voices of those who have done so much for books, readers, and the community. I hope you will join me.

If you are interested in contributing your story, you will find all the details at bookstorechronicles.org.

The American Booksellers Association, which has given up its offices, is donating its extensive organizational and bookseller archives to Columbia University's Rare Book & Manuscript Library, part of the Columbia University Libraries system. The archives include first-edition titles on bookselling, ABA membership photos dating back to the turn of the 20th century, and historical documents about the history of bookselling in the U.S. and the ABA's work since its founding in 1900.

The American Booksellers Association, which has given up its offices, is donating its extensive organizational and bookseller archives to Columbia University's Rare Book & Manuscript Library, part of the Columbia University Libraries system. The archives include first-edition titles on bookselling, ABA membership photos dating back to the turn of the 20th century, and historical documents about the history of bookselling in the U.S. and the ABA's work since its founding in 1900.

In early December last year, I found myself holding an old photograph of a group of booksellers, seated at an event, posing with a famous author. The photograph was from 1902. The author was Mark Twain. In the box were more photos: storefronts of long-gone famous bookstores, booksellers deep in conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr., booksellers standing in the Oval Office with various presidents, photographs of some of my mentors and book folk whom I admired, looking as young as I was when I met them.

In early December last year, I found myself holding an old photograph of a group of booksellers, seated at an event, posing with a famous author. The photograph was from 1902. The author was Mark Twain. In the box were more photos: storefronts of long-gone famous bookstores, booksellers deep in conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr., booksellers standing in the Oval Office with various presidents, photographs of some of my mentors and book folk whom I admired, looking as young as I was when I met them.

The executive board of the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) met recently in Bridgewater, N.J., to review and update their organizational strategies leading up to BISG's 50th anniversary in 2026. Pictured: (l.-r.) Jason Wells (American Psychological Association), Sabbithry Persad (Firewater Media Group), Allen Johnson (Baker & Taylor), Mike Feinson (Engaged Strategies), James Miller (Barnes & Noble), Paul Gore (FADEL), Todd Carpenter (National Information Standards Organization), Kevin Spall (Scholastic), Bridget Marmion (Bridget Marmion Book Marketing), Joshua Tallent (Firebrand Technologies), Matt Kennel (Versa Press), Brian O'Leary (BISG), Benjamin Spira (Dentons), Brooke Horn (BISG), Andrea Fleck-Nisbet (Independent Book Publishers Association).

The executive board of the Book Industry Study Group (BISG) met recently in Bridgewater, N.J., to review and update their organizational strategies leading up to BISG's 50th anniversary in 2026. Pictured: (l.-r.) Jason Wells (American Psychological Association), Sabbithry Persad (Firewater Media Group), Allen Johnson (Baker & Taylor), Mike Feinson (Engaged Strategies), James Miller (Barnes & Noble), Paul Gore (FADEL), Todd Carpenter (National Information Standards Organization), Kevin Spall (Scholastic), Bridget Marmion (Bridget Marmion Book Marketing), Joshua Tallent (Firebrand Technologies), Matt Kennel (Versa Press), Brian O'Leary (BISG), Benjamin Spira (Dentons), Brooke Horn (BISG), Andrea Fleck-Nisbet (Independent Book Publishers Association).

"Just a reminder that our

"Just a reminder that our

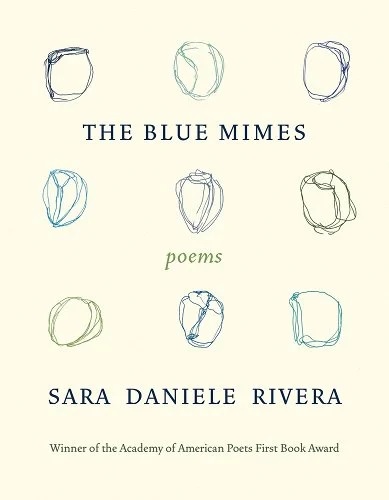

Winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award, Cuban Peruvian poet Sara Daniele Rivera uses language with artistry in The Blue Mimes, moving from English to Spanish with a lovely musicality. The collection of 27 poems opens with an epigraph in Spanish from Alejandra Pizarnik's "La noche de Santiago." The English translation reads, "Close a wound a bell cannot. A bell cannot close a wound," and this reflexive structure reveals much about Rivera's work. She, too, will play with beginnings and endings and inverted repetitions, especially in "Telephone Game," which begins with "I spoke. You. Sound converted and delivered./ We smiled and spoke." At the midpoint, a couplet of lines both begin "Mimic me:" with the second line repeating the first line in Spanish. From there, the poem rewinds, fully in Spanish, and concludes with, "Una luz convertida se entrega en mi cuerpo. Yo hablo. Tú./ Hablamos y sonreímos." More than just a clever trick, this poem reveals a sense of longing, especially with the shift from past tense to present.

Winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award, Cuban Peruvian poet Sara Daniele Rivera uses language with artistry in The Blue Mimes, moving from English to Spanish with a lovely musicality. The collection of 27 poems opens with an epigraph in Spanish from Alejandra Pizarnik's "La noche de Santiago." The English translation reads, "Close a wound a bell cannot. A bell cannot close a wound," and this reflexive structure reveals much about Rivera's work. She, too, will play with beginnings and endings and inverted repetitions, especially in "Telephone Game," which begins with "I spoke. You. Sound converted and delivered./ We smiled and spoke." At the midpoint, a couplet of lines both begin "Mimic me:" with the second line repeating the first line in Spanish. From there, the poem rewinds, fully in Spanish, and concludes with, "Una luz convertida se entrega en mi cuerpo. Yo hablo. Tú./ Hablamos y sonreímos." More than just a clever trick, this poem reveals a sense of longing, especially with the shift from past tense to present.