Among the many contributors to Among Friends: An Illustrated Oral History of American Book Publishing & Bookselling in the 20th Century, published last fall by Two Trees Press and distributed by Ingram Content Group, is Anita Silvey, who has worked at the Horn Book and Houghton Mifflin. Here we reproduce her contribution, which focuses on how children's books "came out from under the staircase."

Among the many contributors to Among Friends: An Illustrated Oral History of American Book Publishing & Bookselling in the 20th Century, published last fall by Two Trees Press and distributed by Ingram Content Group, is Anita Silvey, who has worked at the Horn Book and Houghton Mifflin. Here we reproduce her contribution, which focuses on how children's books "came out from under the staircase."

On the night of July 20, 2011, along with a few hundred people, I waited in a suburban bookstore for the release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part II. As I looked around the energized crowd, I reflected on my 40 years in children's book publishing. In 1970, as a lowly editorial assistant for Ralph Woodward, publisher of children's books at Little, Brown, I could never have imagined the scene before me. At that time the general public had little knowledge of any new children's book. Even the publishing houses where I worked largely ignored everything we did. A poster on the fifth floor of Houghton Mifflin's offices, which housed the children's book department, read: "We Scream, and No One Listens." But now the most valued book to be published in the world, a children's book, would sell millions at midnight.

The children's book industry as known today began in 1919, when Louise Seaman Bechtel, the first children's book-only editor, was appointed at Scribners. Those early editors believed in good books for boys and girls—or as Ursula Nordstrom of Harper and Row used to say, "good books for bad boys and girls." Poet Walter de la Mare set the standard: "Only the rarest kind of best in anything is good enough for the young." These pioneers struggled to offset the popularity of series fiction (Stratemeyer Syndicate's Tom Swift, Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew). But they often created, as Bechtel lamented, "books in search of children." For decades the children's publishing professionals, almost eliminated during the Great Depression, attempted to build an audience for their books. From the beginning, children's publishing would rely on a unique but difficult structure: adults wrote, produced and bought the books before children had a chance to evaluate them.

Those who entered the field quickly learned to lower expectations. As I was told in 1970, nobody needed a children's book department. Small print runs, small advances and focus on sales to the institutional market (librarians and teachers) became the cornerstones of the industry. No New York Times bestsellers for us, and no fancy parties or budgets. Like Harry Potter, we lived under the staircase, in the basement or in the attic.

However, if a house had managed to attract one of those editors who really understood children and often remembered in detail their own childhood, they could start adding titles like Charlotte's Web (Harper), Madeline (Viking) or Green Eggs and Ham (Random House). The sweet spot for children's books was the steady teddies—the backlist titles that generated a very high profit margin.

At one point in my career at Houghton Mifflin, an enthusiastic young CFO came into my office because he had found the panacea for all of the trade department's woes—just publish children's backlist titles. He wasn't necessarily wrong, although doing so would always be more difficult than he imagined. Often in the 1970s, '80s and '90s, publishers measured their children's book departments by how successfully they generated backlist.

By the second half of the 20th century, brilliant and talented editors graced almost every major house. Ursula Nordstrom, reigning genius of midcentury publishing, found Maurice Sendak working as an FAO Schwarz window dresser; Margaret McElderry (Harcourt, Atheneum), elegant and brilliant, stood as the figure that every young editorial assistant wanted to emulate. Dick Jackson (Bradbury, DK, Simon & Schuster) trained and inspired young members of the community. Susan Hirschman (Greenwillow) insisted on quality and content in everything she published and served as a fierce advocate for all her authors and books. Regina Hayes tastefully reissued and packaged the Viking backlist and added contemporary stars to the list.

For much of my career I worked with one of the 20th century lions, Walter Lorraine of Houghton. He had an eagle eye for unpublished talent, and by the end of the century had built an amazing list, still envied by editors, that included Chris Van Allsburg, Polar Express; Lois Lowry, The Giver; David Macaulay, Building Big; and Jim Marshall, George and Martha. Every year he managed to make close to a 25% profit margin. That required more than great authors. Walter kept tabs on every penny; we even knew that small, rather than large, paper clips helped the bottom line.

However, transforming the children's and young adult book publishing industry in the last part of the 20th century required talents other than counting pennies and publishing backlist. Before Harry Potter could become a reality, publishers needed to focus on ways to make frontlist titles attractive to the general bookstore patron. They had some help in the late 1960s, when the Lyndon Johnson administration provided federal funding for libraries; it was a heyday for any title that might fit the school and library market. Then in the 1980s pioneer retailers began to establish children's-only bookstores, with well-chosen stock and trained staff. Great taste and handselling made these stores, all over the country, popular with families and educators.

A few publishers, like Holiday House, Candlewick and Scholastic, realized that being a children's-only publisher would give them an edge in the marketplace. Scholastic brought out one bookstore hit after another (Baby Sitters Club, Goosebumps). Then, to become the largest children's trade book publisher in America, they launched Harry Potter. An amazingly talented trio (CEO Barbara Marcus, publisher Jean Feiwel and editor Arthur Levine) became a solid gold chain.

Like those who shaped the field, children's book professionals have always held strong opinions on what should be published. "Irrefutable truths," as Walter insisted. Viewpoints differ as to what makes the best books for children—books children love, books parents want, books the gate-keepers or critics support, books that win awards? But in the end, we were all searching for, editing, designing and championing the books that could turn reluctant readers into lifelong readers, titles remembered so fondly in adult years because they convinced children that true magic could be found in the pages of a book. In our own ways, we all sought to publish "the rarest kind of best."

Postscript: In the 21st century, children's and YA sales skyrocketed; one title or series after another climbed the New York Times bestseller list. Only 21st century publishers would truly address the lack of racial and sexual diversity in these books.

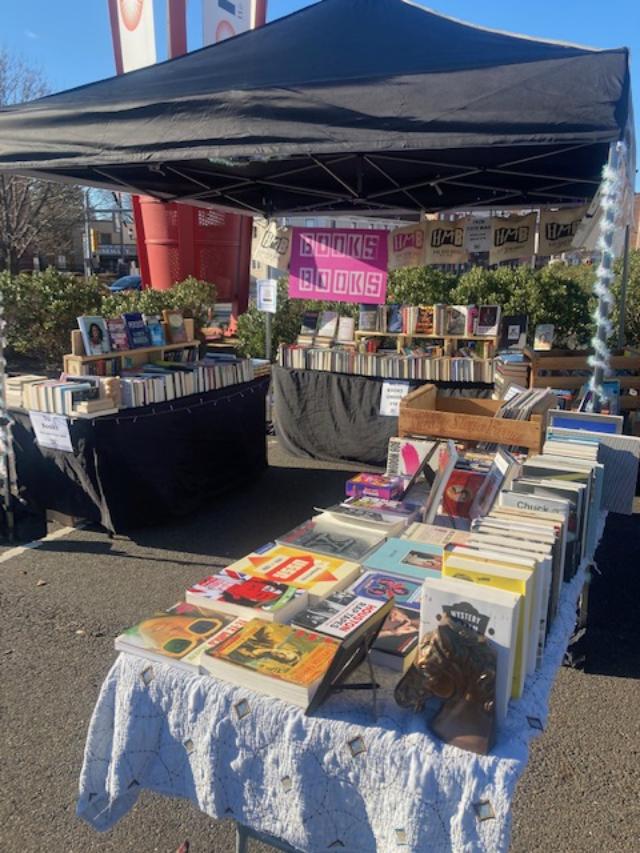

Hive Mind Books, a general-interest bookstore with an emphasis on queer and trans literature, has debuted as an online and pop-up shop in New York City.

Hive Mind Books, a general-interest bookstore with an emphasis on queer and trans literature, has debuted as an online and pop-up shop in New York City. "While Hive Mind is a general-interest bookstore, I am especially interested in curating queer and trans book fairs and supporting all marginalized authors with our selection," Wernersbach explained. "I'm also excited to continue supporting authors by providing book sales at off-site events."

"While Hive Mind is a general-interest bookstore, I am especially interested in curating queer and trans book fairs and supporting all marginalized authors with our selection," Wernersbach explained. "I'm also excited to continue supporting authors by providing book sales at off-site events."

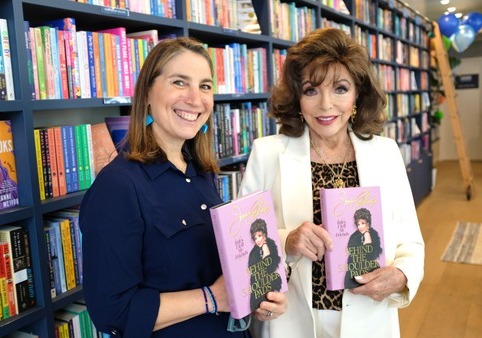

As part of its first anniversary celebration weekend,

As part of its first anniversary celebration weekend,  "It's a beautiful day to visit your local independent bookstore,"

"It's a beautiful day to visit your local independent bookstore,"  Four Minutes: A Thriller

Four Minutes: A Thriller The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, in partnership with the de Grummond Children's Literature Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM), announced the winners of the 2024 Ezra Jack Keats Awards. The awards are given annually to an outstanding new writer and new illustrator. The awards ceremony will be held on Thursday, April 11, during the Fay B. Kaigler Children's Book Festival at USM in Hattiesburg, Miss. The ceremony will be livestreamed beginning at 1 p.m. Eastern.

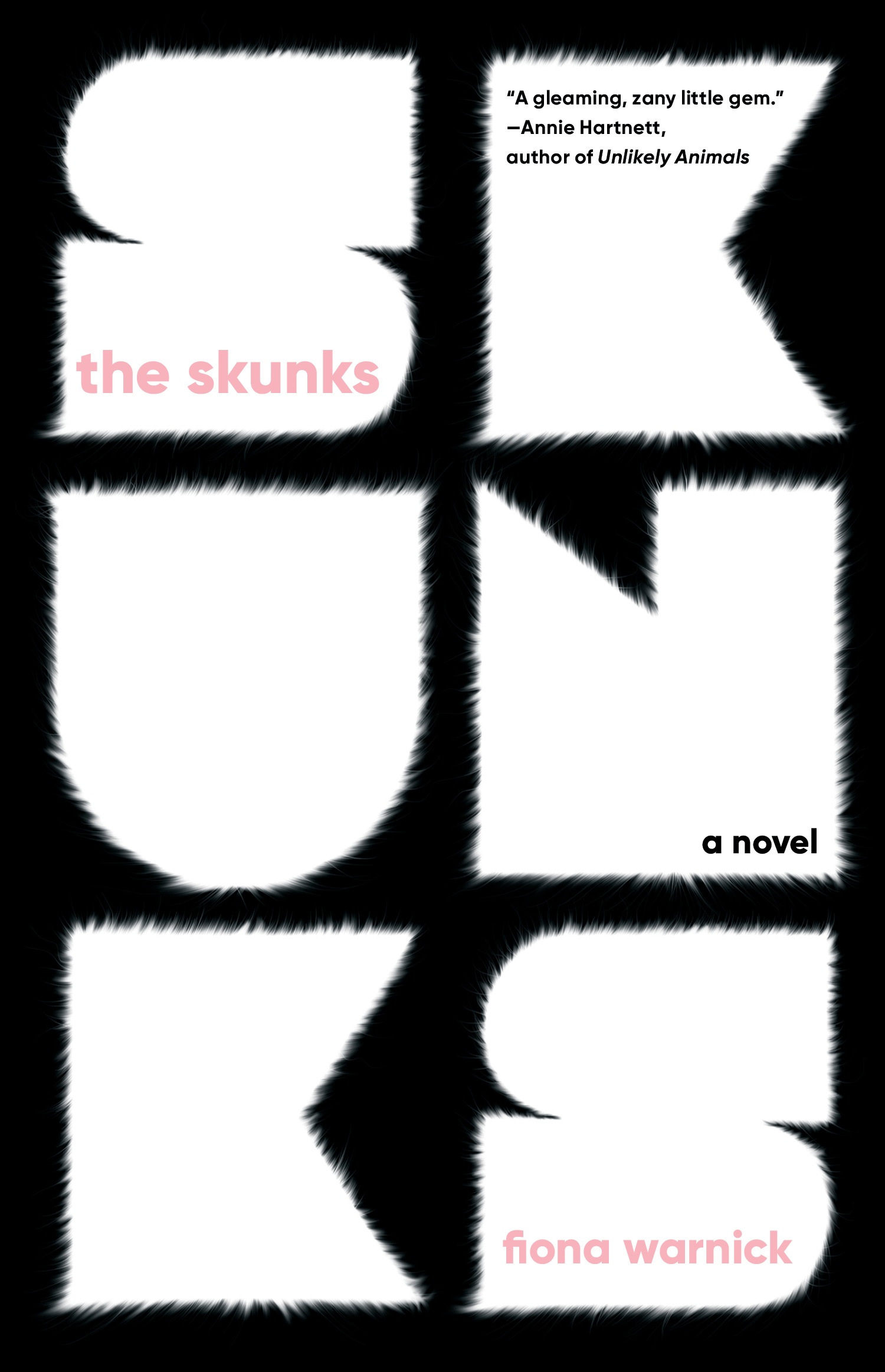

The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, in partnership with the de Grummond Children's Literature Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM), announced the winners of the 2024 Ezra Jack Keats Awards. The awards are given annually to an outstanding new writer and new illustrator. The awards ceremony will be held on Thursday, April 11, during the Fay B. Kaigler Children's Book Festival at USM in Hattiesburg, Miss. The ceremony will be livestreamed beginning at 1 p.m. Eastern. Fiona Warnick's debut, The Skunks, is a tender coming-of-age story about a college graduate's return to her sometimes stifling, sometimes comforting hometown. Speared with honest yet generous insights into summer-after-college dilemmas and angst, Warnick's novel captures the tender nostalgia of time spent in the liminal space between adolescence and adulthood.

Fiona Warnick's debut, The Skunks, is a tender coming-of-age story about a college graduate's return to her sometimes stifling, sometimes comforting hometown. Speared with honest yet generous insights into summer-after-college dilemmas and angst, Warnick's novel captures the tender nostalgia of time spent in the liminal space between adolescence and adulthood.

Among the many contributors to

Among the many contributors to