|

| photo: Vino Wong |

Parul Kapur holds an MFA from Columbia University and has worked as a journalist, critic, and fiction writer for much of her life. Her writing has appeared in Ploughshares, Pleiades, the New Yorker, the Wall Street Journal Europe, Slate, Guernica, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Paris Review. Her debut novel, Inside the Mirror (University of Nebraska Press, March 1, 2024), is an examination of art, colonialism, injustice, love, and the ambition of women to seize their own power, and it won the AWP Prize for the Novel.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

In 1950s India, visionary twin sisters battle a protective family and shaming society to claim their powers as artists--a painter and a dancer.

On your nightstand now:

Near to the Wild Heart by Clarice Lispector, a name I first heard from my dearest friend in graduate school, long before Lispector became a figure of fascination in American letters as a bold and provocative woman writer.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, an intergenerational family saga I'm anticipating like a great Indian feast.

If Bomber by Len Deighton had not been a book club selection, I might never have picked up this magnificent novel, since Deighton is known as a spy novelist. Here he has created a suspenseful and deeply human story about a World War II British bombing unit preparing to destroy a city in Germany's Ruhr valley, where my husband grew up in the postwar era.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Any of the six Nancy Drew mysteries by Carolyn Keene my mother bought me at a garage sale. The Secret of the Wooden Lady might have been the first book that got me hooked on Nancy, the astute girl "sleuth." As an immigrant child, I wished I could be as brave, confident, and admired as Nancy Drew.

Your top five authors:

For their staggering powers of observation and extraordinary skill with language, I admire the writers below as literary artists and not the tarnished human beings some of them have been exposed as (specifically, the two late Nobel Prize winners at the end of my list). I would drop everything to pick up a book I hadn't heard of by any of these geniuses: James Joyce, Charlotte Brontë, Jesmyn Ward, V.S. Naipaul, and Derek Walcott (sneaking in a poet whose world-building is supremely novelistic).

Book you've faked reading:

Albert Camus's La Peste (The Plague in English), an allegory of war and resistance, is a novel few of us in 10th-grade French were linguistically equipped to tangle with. As my eyes roamed over the sentences, my brain would light up whenever a familiar noun or verb appeared, but never came to a conclusive understanding of a paragraph, let alone a page. Class discussions were a time to direct my gaze anywhere but in the direction of the teacher, who might call on me.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

This Is Not That Dawn by Yashpal, a prolific writer imprisoned as a revolutionary in colonial India, is the most magnificent tale ever told of the tragedy of modern India. It begins with the domestic squabbles of a lower-middle-class Punjabi family in the city of Lahore, takes us through appalling and riveting scenes of horror and violence as the British divide the subcontinent into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan, resulting in millions killed, and moves beyond that calamity to a broken India picking up the shattered pieces of itself in the 1950s. Originally written in serial form for a Hindi magazine, whose spellbound readers sent sacks of mail to the author's home, This Is Not That Dawn endured a long search for an English translator. Finally, the author's son, Anand, turned his hand to translating the 1,000-page tome, which has been compared with Tolstoy's War and Peace.

Book you've bought for the cover:

The Harrad Experiment by Robert Rimmer. As a curious middle-school-aged observer of the sexual revolution in the wild and woolly '70s, I chipped in to buy this book with my best friend, attracted by the risqué image of a young couple on the cover.

Book you hid from your parents:

The Harrad Experiment (see above). My friend and I took turns reading Rimmer's story about free love breaking out on a campus where students are assigned roommates of the opposite sex. I read the paperback in an old garden shed I'd converted into my hideout in our backyard edging a cemetery, poised between my great ignorance of sex and my great ignorance of death.

Book that changed your life:

I knew from a young age I wanted to be a writer. But reading Mrs Dalloway in my early 20s, I was swept up by shimmering flights of language, and believed I'd found my literary style: it would be lyrical, like Virginia Woolf. I saw Mrs Dalloway as a purely aesthetic work, untethered to history, since I knew so little history myself then. Recently I picked the book up again and couldn't read past a few chapters. All I saw was the characters' blithe complicity in colonialism: Clarissa Dalloway, her friend Peter, just returned from India, and others of the ruling class expected at her party represented the British elite who most richly benefitted from Empire, at the cost of crushing generations of Indians, including my family. As we evolve, so does our view of books we've loved.

Favorite line from a book:

"So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past." --F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby.

Five books you'll never part with:

There is no single storyline in my favorite books, but multiple paths of exploration. I would never give up Ulysses by James Joyce, a day in the life of Leopold Bloom, his unfaithful and beloved wife (Molly), his city (Dublin) and his world (Ireland).

A House for Mr. Biswas by V.S. Naipaul, equally a comedy and tragedy about an ambitious yet powerless son of Indian indentured servants in colonial Trinidad.

Agaat by Marlene van Niekerk, translated from Afrikaans by Michiel Heyns, a tour-de-force portrayal of a bedridden white farm wife in South Africa utterly dependent on the Black girl she once domineered over as a servant and kind of daughter.

Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz, part of his Cairo Trilogy, whose scenes depicting the mundane and terrifying ways in which a wife and children are subjugated by the patriarch are so vivid they sear into the mind forever.

Douglas Stuart's Shuggie Bain is a surprising masterpiece by an author trained in fashion who paints this intricate, autobiographical portrait of a boy and his vainglorious, alcoholic mother struggling in soot-stained, down-and-out Glasgow with astounding skill.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead is an utterly enchanting book, for all the savagery it contains of the treatment of the enslaved. It seems to me he took some of the real-life brutalities and peculiarities of enslavement, and mixed it with speculative elements, to evoke the terrifying strangeness of a country that normalized slavery. Every chapter came as a surprise to me, and I wish I could experience again how Whitehead connects one astonishing phenomenon to the next.

But there are stupider things to spend your money on. There are so many bookstores in the Bay Area to love. My two favorites have always been Walden Pond and Spectator Books."

But there are stupider things to spend your money on. There are so many bookstores in the Bay Area to love. My two favorites have always been Walden Pond and Spectator Books."

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

The American Booksellers Association has announced the names of the 30 booksellers who will receive scholarships to attend this year's

The American Booksellers Association has announced the names of the 30 booksellers who will receive scholarships to attend this year's

Author Soyoung Park (center) and translator Joungmin Lee Comfort (left) celebrated the release of their YA dystopian novel Snowglobe (Delacorte) with a launch event at the Korea Society in New York City. The event was moderated by author Kat Cho (right) and book sales were handled by

Author Soyoung Park (center) and translator Joungmin Lee Comfort (left) celebrated the release of their YA dystopian novel Snowglobe (Delacorte) with a launch event at the Korea Society in New York City. The event was moderated by author Kat Cho (right) and book sales were handled by  "Did we really need

"Did we really need

Staying Connected with Your Teen: Polyvagal Parenting Strategies to Reduce Reactivity, Set Limits, and Build Authentic Connection

Staying Connected with Your Teen: Polyvagal Parenting Strategies to Reduce Reactivity, Set Limits, and Build Authentic Connection

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Yesterday was

Yesterday was

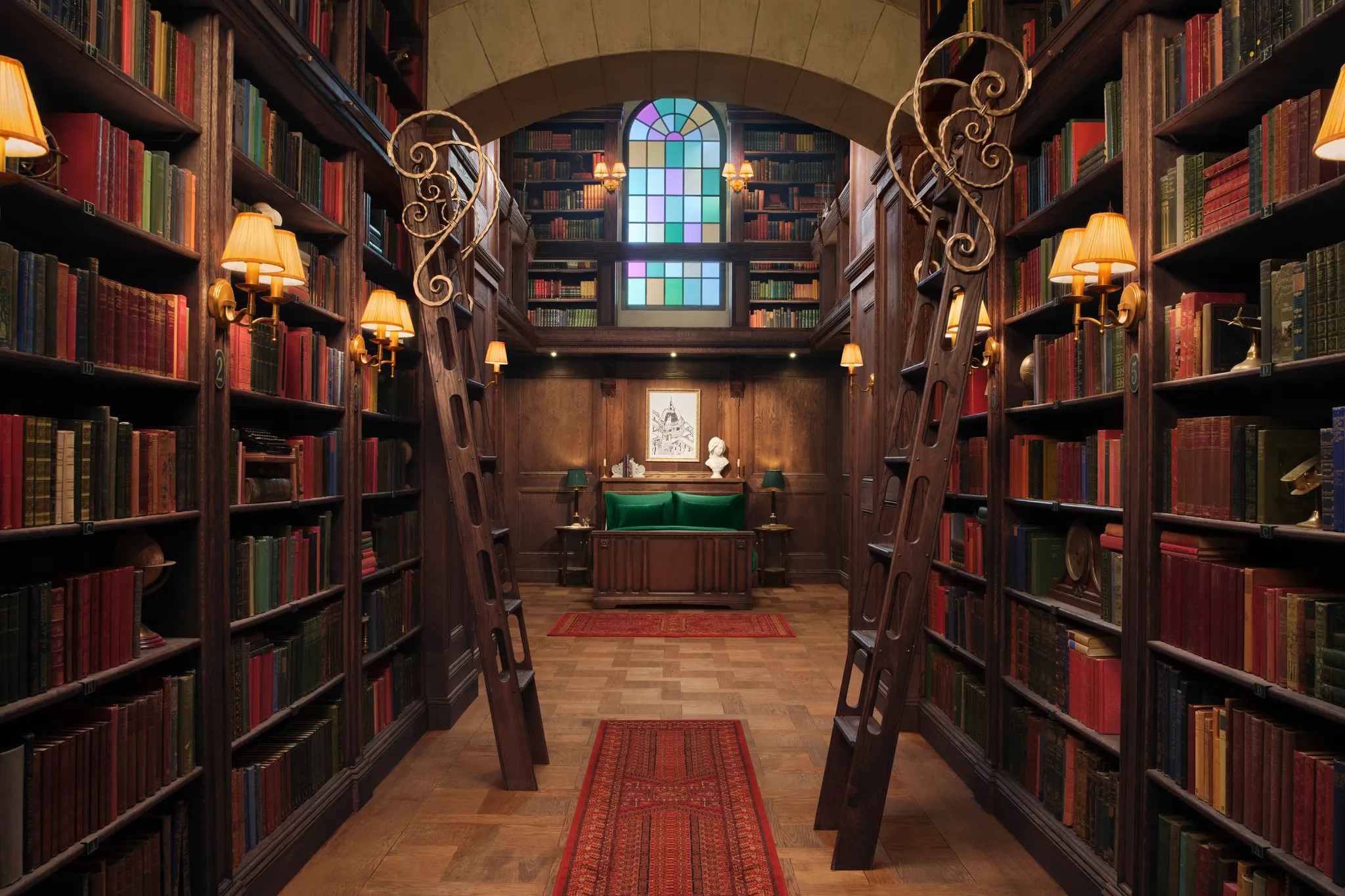

Describing the Hidden Library as "a magical space," Airbnb noted that the two lucky guests who stay there "will be the first to officially sleep inside the Cathedral since the St. Paul's Watch protected the building during World War II. You will enter the iconic St. Paul's Cathedral through the Dean's door and climb the famous Geometric Staircase, designed by English architect Sir Christopher Wren over three hundred years ago. You will be greeted by the Dean of St. Paul's and receive an exclusive tour of the Cathedral. At the top of the staircase, you will enter the doors to the charming library space, and be given the exclusive opportunity to lose track of time in the pages of Holly Jackson's The Reappearance of Rachel Price, John Grisham's Camino Ghosts, and Kevin Kwan's Lies and Weddings before they hit the shelves."

Describing the Hidden Library as "a magical space," Airbnb noted that the two lucky guests who stay there "will be the first to officially sleep inside the Cathedral since the St. Paul's Watch protected the building during World War II. You will enter the iconic St. Paul's Cathedral through the Dean's door and climb the famous Geometric Staircase, designed by English architect Sir Christopher Wren over three hundred years ago. You will be greeted by the Dean of St. Paul's and receive an exclusive tour of the Cathedral. At the top of the staircase, you will enter the doors to the charming library space, and be given the exclusive opportunity to lose track of time in the pages of Holly Jackson's The Reappearance of Rachel Price, John Grisham's Camino Ghosts, and Kevin Kwan's Lies and Weddings before they hit the shelves."