RISE Bookselling Conference: Oleksii Erinchak on Wartime Bookselling in Ukraine

"The 23rd of February we were wearing masks. The 24th, no masks, no coronavirus," said Oleksii Erinchak, owner of the Ukrainian bookstore Sens (Сенс), recalling the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. "War is a much bigger problem."

"The 23rd of February we were wearing masks. The 24th, no masks, no coronavirus," said Oleksii Erinchak, owner of the Ukrainian bookstore Sens (Сенс), recalling the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. "War is a much bigger problem."

Erinchak appeared on Sunday at the RISE Bookselling Conference in Riga, Latvia, in conversation with Raluca Selejan, co-owner of La Două Bufniţe in Timisoara, Romania. He discussed the background behind his bookstore, the effect the war has had on his business as well as Ukrainian literary culture, and what booksellers around the world can do to help.

Erinchak said he decided to open a bookstore after noticing that there was a lack of places in his Kyiv neighborhood where community members could meet, have a chat, and connect. He chose a storefront on the first floor of his apartment building, recently vacated by a restaurant, and decided that a combination bookstore and cafe would be a more interesting option for the community than just a cafe.

|

|

|

Raluca Selejan with Oleksii Erinchak (r.) |

|

Prior to the invasion, Erinchak reported, roughly 80% of Ukraine's book market consisted of Russian-language titles. From the beginning he decided to carry titles only in Ukrainian. People would say things like "there's nothing to read in Ukrainian," and he wanted to show them that there were enough books to read in Ukrainian "for your whole life."

On the day the invasion began, the war "started at 5 o'clock in the morning." Despite that, his barista still came to work, and until about 2 p.m. Sens sold some 75 cups of coffee to community members who arrived in the bookstore in a state of shock. Later that day, Erinchak moved all of the store's seating to a nearby shelter, which was located in a basement and had no seating.

The following day, Erinchak took his family to Romania. When he returned to Kyiv, the bookstore was a "very silent place" because so many had fled. Sens soon became a hub for volunteer groups that had organized in the community, and Erinchak said he couldn't guess "how many tons" of donated supplies, including food and army equipment, passed through the bookstore.

By March 3, people were buying books again, and Erinchak noted that the first book the store sold following the invasion was a book about design. That proved to be a little unusual, as most people turned to books about Ukrainian identity and history. Those sorts of titles, along with books like On Freedom and On Tyranny by Timothy Snyder, continue to be the store's biggest sellers. (Recently, Sens hosted a standing-room-only event for Snyder; there were 400 registrations in the first 30 minutes they were available.)

By March 3, people were buying books again, and Erinchak noted that the first book the store sold following the invasion was a book about design. That proved to be a little unusual, as most people turned to books about Ukrainian identity and history. Those sorts of titles, along with books like On Freedom and On Tyranny by Timothy Snyder, continue to be the store's biggest sellers. (Recently, Sens hosted a standing-room-only event for Snyder; there were 400 registrations in the first 30 minutes they were available.)

Asked how the war has affected everyday activities at the bookstore, Erinchak said the single most important thing he can offer both staff and customers is "psychological support." If a staff member can't come in due to emergency sirens disrupting their commute, "no one is asking, 'Why can't you come?' " Likewise, if someone is late or simply in a bad mood because sirens kept them up at night, it isn't held against them.

"This is our life," he said. "We've lived it three-plus years."

Erinchak has also bought generators and "huge batteries" to cope with the frequent power disruptions and, given the potential for supply-chain issues, he and his team try to identify big titles early and order as many as possible.

Erinchak has also bought generators and "huge batteries" to cope with the frequent power disruptions and, given the potential for supply-chain issues, he and his team try to identify big titles early and order as many as possible.

One side effect of the invasion, Erinchak added, has been a "boom" in the amount of Ukrainian-language titles. The departure of Russian-language publishers left a huge gap in the market, and the number of Ukrainian publishers "started to grow." In fact, publishers are growing so fast that it has led to short print runs, as they "cannot afford to print more," he said.

He further pointed to "problems with discounts" in Ukraine, and said that he does not give discounts in order to show others in the market that "it is possible to work like this." Rather than "kick each other," they should "develop the book market together."

During the bookstore's first year, the most common feedback Erinchak heard was that the space was too crowded, especially during events, and a particular standing-room-only author event made Erinchak decide to open a bigger location. It was clear, he said, that "Ukrainian culture and literature have a lot of people who want to participate."

On February 16, 2024, the second Sens location opened. It spans roughly 16,000 square feet and sees some 50,000 visitors each month, with Erinchak noting that young people between the ages of 16 and 27 make up the store's "biggest audience." Laughing, Erinchak related that when the second location opened, his team said the space was too huge. After only two months, they started saying the space was "too small for us."

The bookstore and its audience have continued to grow, and earlier this year, Sens opened a third store in western Ukraine. It also produces a monthly newspaper that talks about the store, books, and the broader book community. Print runs consist of 10,000 copies, and copies are distributed for free in-store.

Asked how booksellers in other countries can offer support, Erinchak said they can work to support democracy in their own countries, sell books like those by Timothy Snyder, and "quarantine" Russian authors until the end of the war.

When an audience member floated the idea of donating money to support Sens, Erinchak instead urged people to donate to organizations that support the Ukrainian army. Addressing an audience made up almost entirely of European booksellers, in a country bordering Russia, he emphasized that if not for the Ukrainian army, "you will face Russia at your door next." --Alex Mutter

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Samuel Ashworth (l.) launched his debut novel, The Death and Life of August Sweeney (Santa Fe Writer's Project), at

Samuel Ashworth (l.) launched his debut novel, The Death and Life of August Sweeney (Santa Fe Writer's Project), at  "Last month, we had

"Last month, we had  Hazel the Handful

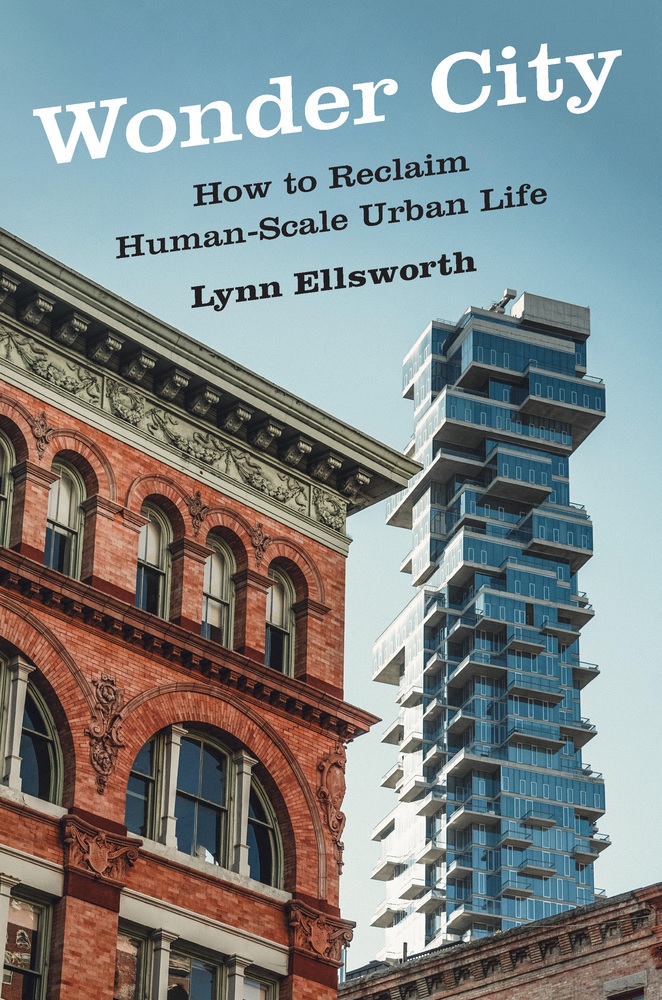

Hazel the Handful Amid the real-estate development battle between advocates of "hyper-dense" urban living with ever-taller towers at the center, and those who instead push for a return to human-scale city life, Wonder City is a call to action in which Lynn Ellsworth deftly argues in favor of the latter. This rigorously researched but approachable volume navigates architectural philosophy, legal precedent, and historical building patterns. It unravels the intricacies and flaws of regulatory boards in a way that will leave even readers new to the topic feeling more informed. Urban activist and economist Ellsworth's organized approach aims to bring more people to this conversation--not just those who might already be involved on various sides of the fight--and she makes the stakes of losing the "wonder city" clear not only for New York City but for urban development everywhere.

Amid the real-estate development battle between advocates of "hyper-dense" urban living with ever-taller towers at the center, and those who instead push for a return to human-scale city life, Wonder City is a call to action in which Lynn Ellsworth deftly argues in favor of the latter. This rigorously researched but approachable volume navigates architectural philosophy, legal precedent, and historical building patterns. It unravels the intricacies and flaws of regulatory boards in a way that will leave even readers new to the topic feeling more informed. Urban activist and economist Ellsworth's organized approach aims to bring more people to this conversation--not just those who might already be involved on various sides of the fight--and she makes the stakes of losing the "wonder city" clear not only for New York City but for urban development everywhere.

Will there be a bookish

Will there be a bookish  "I'm hoping that this hasn't been thought through," Neill, who also owns

"I'm hoping that this hasn't been thought through," Neill, who also owns

Stranger than fiction.

Stranger than fiction.