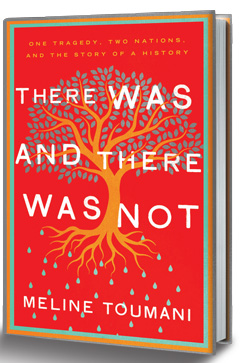

There Was and There Was Not

by Meline Toumani

In 2005, Armenian-American journalist Meline Toumani traveled to Turkey--a place she had previously known only as "a terrifying idea"--with the intention of studying Armenia-Turkey relations for a month or two, three at the most. She stayed for two years, with the help of regular "visa runs" over the border. The result of her immersion in a culture she had been trained to "hate, fear and fight" is There Was and There Was Not: A Journey Through Hate and Possibility in Turkey, Armenia and Beyond, an engaging and deeply personal exploration of ethnicity, nationalism, history and identity.

The conflicting Armenian and Turkish narratives regarding the massacre of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915 defined the Armenian diaspora community of Toumani's childhood. On the one hand, Turkey has historically denied that the massacre existed, or minimized the scale of the deaths. On the other hand, the Armenian community focuses substantial energy on campaigns designed to pressure the Turkish government to recognize the massacre as genocide. Toumani had reached the point where the dominance of the genocide narrative felt like an artistic and emotional chokehold. She set out to Turkey in an attempt to answer two questions: How could she honor her history without being suffocated by it, and why do Turks cling to their version of the events of 1915?

Toumani brings the reader along on a voyage of discovery that begins with her growing doubts about the emotional, psychological and political costs of the Armenian diaspora's focus on Turkish recognition of the genocide; it ends with Toumani defying rules about neutrality in the press box by screaming her support of Armenia at a World Cup match between Armenia and Turkey in Istanbul. In between, she tells a story riddled with unreliable narrators, unreliable listeners, lost memories, lost history, false assumptions and real places transformed by the imagination. She establishes the constantly shifting ground of her experience at the beginning when her plane lands in Istanbul and she realizes she has never imagined Turkey as a physical place. She is stunned by the country's beauty and charmed by what she describes as the "particular sweetness of Turkish manners"; she actively enjoys learning the Turkish language. (The contrast between Toumani's phobia about speaking Armenian and her delight in learning Turkish is typical of her skilled use of irony and reversal to enrich her narrative.) At the same time, she is repeatedly dismayed and occasionally enraged by the ways in which Turkey erases traces of the Armenian past: the opening ceremony of a newly renovated Armenian church as a UNESCO world heritage site that makes no reference to Armenians; a museum visit in which she discovers that hundreds of years of Armenian civilization in Anatolia don't appear on the time line or the map; brochures and travel guides that describe Armenian artifacts in southeastern Turkey but never identify them as Armenian.

Moving between Turkey and the Republic of Armenia, Toumani shares her experiences of events as important as the assassination of Turkish-born Armenian journalist and civil rights activist Hrant Dink and as small as the street vendors calling their wares on the street outside her apartment. She finds friends and allies among the Turkish activists, journalists, scholars and lawyers who have taken up the Armenian issue, often at the risk of prison or worse. She speaks to millionaires, dentists and cab drivers; Turkish scholars dedicated to cooperating across ethnic lines and Turkey's official historian; Turkish-Armenians and Armenians from the former Soviet republic; Kurds, Turkish nationalists and an ethnic Turk who refuses to identify himself as Turkish. She encounters Turks who are uncomfortable with the fact that she is Armenian and Turks who struggle to find a point of connection (described by Toumani as the "narcissism of small similarities").

Over the course of the book, the clear-cut oppositions with which Toumani begins her project become more nuanced. Even the unity of the Armenian community itself becomes more complex as she examines the different concerns of the diaspora; Turkish-Armenians (described by members of the diaspora community as Bolsahay--a term that avoids describing them as Turkish) and citizens of the Republic of Armenia; those whose families survived the genocide and those whose families were not directly involved; and the ideological divide between those who support the activist Dashnak Party of the Republic and those who do not.

There Was and There Was Not is neither a history of the genocide nor an examination of its political ramifications for the modern world. It is the story of one woman's attempt to understand her community, its fundamental assumptions, and herself. Written in a conversational style that is by turns heart-wrenching and unexpectedly funny, There Was and There Was Not will appeal not only to those interested in questions of the Armenian genocide but to readers interested in the larger questions of how individuals define themselves within communities and how communities define themselves. --Pamela Toler

.jpg)