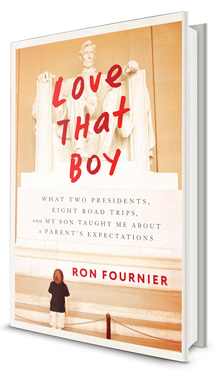

Love That Boy: What Two Presidents, Eight Road Trips, and My Son Taught Me About a Parent's Expectations

by Ron Fournier

Love That Boy: What Two Presidents, Eight Road Trips, and My Son Taught Me About a Parent's Expectations offers many things: memoir, parenting advice, meditations on Asperger's Syndrome and even short discursions into the lives and personalities of various presidents. In other words, Love That Boy is not the straightforward narrative one might expect from Ron Fournier, an experienced journalist who's covered multiple presidents for the Associated Press. Instead, Fournier has written a searching, introspective book that examines his relationship with his son Tyler, diagnosed at an early age with Asperger's.

Fournier presents himself in a surprisingly unforgiving light. Perhaps he is attempting to replicate his son's penchant for blunt honesty, a common Aspergian trait, when he regretfully recalls how his workaholic tendencies combined with the requirements of his profession led him to leave his family for lengthy periods. He describes his job as "an ego-inflating career that I often put ahead of my wife and kids" and wonders whether his preoccupations prevented him from recognizing the symptoms of high-functioning autism in Tyler: "his pseudo-adult intellect, vocabulary, and baritone; his awkward social interactions and obsessions; his aversion to certain fabrics, the comfort he found in a weighty blanket, and an extraordinarily picky palate."

These bouts of self-criticism, as well as the exhortations of his wife, Lori, lead Fournier to the conceit of the book: so-called "guilt trips" where he would use his professional connections to take Tyler to various historical sites dedicated to deceased presidents as well as meetings with Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama. As Lori put it: "You can use a job that took you away from Tyler to help him now." The idea for the trips stemmed from an interest in presidential history shared by Tyler and his father. Fournier sees it as an opportunity for them to connect after failing to interest Tyler in sports and other traditional bonding activities. Lori sees it as way for "Tyler to interact with a world mostly unlike him." Tyler may be less than enthused, but he does seem to appreciate the opportunity to recite his already-encyclopedic store of presidential knowledge: "As if his brain is a website being queried for presidential information, Tyler pulls up fact after somewhat-related fact. The elder Adams was a lawyer who defended British officers accused of murders resulting from the Boston Massacre. He wrote the Massachusetts constitution, a model for the U.S. document. The Tea Party was just a tax fight. And on and on...."

Fournier admits to feeling uncomfortable and even embarrassed by his son's relentless interruptions, questions and monologues--broken only by bouts of complete silence--and the arc of Love That Boy follows him from that initial stage to a place of acceptance and appreciation for his son's unique personality. He learns these lessons from unusual, often presidential sources. For example, he gains perspective on the danger of parental expectations from Teddy Roosevelt's letters to his sons and learns from Bill Clinton that Tyler's conversation-hogging monologues are far from unique to "Aspies." In fact, Tyler ends up becoming quite comfortable with Clinton, whose lengthy digressions and long silences bear enough similarities to Tyler's own personality that Fournier scribbles down in his notebook "IS BC AN ASPIE????" As they're leaving, Tyler shares a rare compliment: "Nice guy.... He talked a lot about himself and his stuff."

In one instance, Fournier and his son are waiting in line to speak with President Obama. Despite his best efforts, Fournier can't help but worry that his son will act inappropriately, but is ultimately disappointed only in himself when Tyler embraces the First Lady and shakes President Obama's hand while looking him in the eye. It's a moment that forces Fournier to realize "the problem here isn't my son. It isn't even autism. It's me." Even the title, Love That Boy, was said to Fournier by George W. Bush upon meeting Tyler. While Fournier worried that Tyler's clipped conversation might strike President Bush as rude, the President's persistence eventually led to Tyler coming out of his shell and explaining his passion for improv comedy. "I thought I understood what he meant," Fournier writes, reflecting on President Bush's admonition to "love that boy." "I didn't. It took me years to understand."

While Love That Boy provides invaluable information and advice for parents of Aspies--the robust bibliography and numerous quotations attest to the seriousness of Fournier's quest to understand his son and his condition--it's also full of wisdom for parents of "neurotypicals." Again and again, Fournier returns to the problem of expectations. He advises against seeing children "not as they are but as we think they should be" and laments the heavy weight of external expectations felt by parents.

Fournier also warns against "mini-me" parenting--"parents who assume they're raising an echo of themselves." He quotes from Andrew Solomon's Far from the Tree and numerous other texts in support of his point, and draws from interviews with other parents of atypical children, and atypical adults who often recall childhood as a constant struggle not to disappoint their parents. Here, Fournier's reportorial skills come into play as he draws candid admissions from sons and fathers. He quotes Solomon: "Parenthood abruptly catapults us into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity." Fournier reveals the truth of that statement, but also centers his book on a powerful message of empathy. Love That Boy contains important lessons for anyone struggling to relate to the strangers in their own lives.

Still, Fournier is quick to admit that all the empathy in the world won't make parenting easy, let alone parenting an Aspie child. He credits much of Tyler's growth to his admission to a magnet school with programs catering specifically to kids with high-intellect Asperger's and to the team of professionals Lori built to work with Tyler outside of school. Love That Boy does not disguise the fact that raising an Aspie child takes time, patience and, unfortunately, resources many parents do not have. In the epilogue, Fournier makes a moving case for government programs in support of these overwhelmed families. According to him, "every taxpayer must be willing to support public services for children, especially those with special needs. Federal, state, and local governments must invest in child welfare...."

Love That Boy starts in a very personal place, expanding its scope as it goes along. By the time it reaches the point of broad policy proposals and sweeping parenting advice, Fournier's insights feel earned and evidence-based. Without putting too fine a point on it, Love That Boy presents a particular story about Tyler and a universal story about parenthood--its conclusions are born out of this moving interaction between personal experience and time-honored truths. Love That Boy is a must-read for parents and the parented. --Hank Stephenson