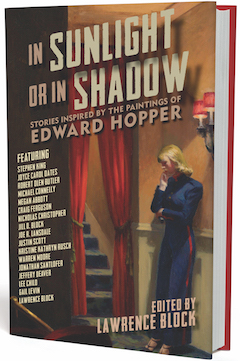

In Sunlight or in Shadow: Stories Inspired by the Paintings of Edward Hopper

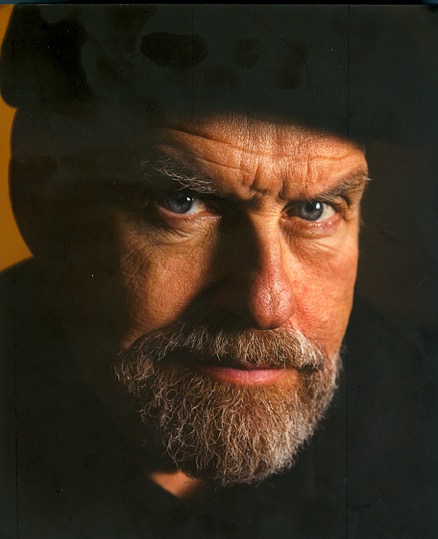

by Lawrence Block, editor

Celebrated crime writer Lawrence Block has assembled a beguiling volume of short stories, all taking inspiration from the paintings of American realist painter Edward Hopper. Each story begins with a short introduction to the featured author and a full-color reproduction of the specific Hopper painting. The stories create vibrant, compelling worlds from Hopper's on-canvas work, each one a peek into the world of complex human relationships.

While Stephen King's "The Music Room"--as twisted a tale as any in the volume, with kidnapping and murder on offer--may be the most high-profile piece in the collection, it's definitely not the only good one. Many of the stories have a strongly feminist stance, perhaps intentionally and ironically at cross purpose with the original painting or the artist himself. Megan Abbott's "Girlie Show" is told from the perspective of Pauline, who poses nude for her painter husband. She overhears him talking about said show with an embarrassed, hushed reverence and realizes that what he's painting may not quite match her own body. The ensuing visit to the theater where the girlie show takes place leads Pauline to an empowering moment, which is depicted in the Hopper painting. Jonathan Santlofer subverts the traditional story of a psychopathic male watching a vulnerable woman through the window in "Night Windows," which will stay with readers long after the compelling denouement. Editor Lawrence Block's contribution, "Autumn at the Automat," is just as subversive, guiding readers to a conclusion that turns out to be as false as it is poignant.

Other stories, like the one from Jack Reacher's creator, Lee Child, find a looser connection with the chosen painting, but nevertheless reference it brilliantly. Hopper's 1943 Hotel Lobby inspired Child's "The Truth About What Happened," about an expert witness and investigator who gives two depositions, one official and one much more informal, to help the FBI vet a potential candidate. Justin Scott honors the nude subject of Hopper's A Woman in the Sun with a quick story about lovers, the beach and tennis.

Many of the pieces, though, deal directly with the human subjects of their paintings, including Joe R. Landsdale's "The Projectionist," which reveals the story of the young usherette in Hopper's New York Movie. Jill D. Block's "The Story of Caroline" was inspired by Hopper's 1947 canvas Summer Evening. A middle-aged woman named Hannah, adopted as a child, returns as a hospice worker to the family that gave her up, to help care for the dying father. Finding her biological mother, Grace, as well as two other unknown siblings, is an opportunity that Hannah, once named Caroline, cannot pass up. Gail Levin, a professor of art history and biographer of Hopper, turns in "The Preacher Collects," an account of a reverend who takes advantage of his position as the spiritual counsel to Edward Hopper's aging sister at the end of her life.

Warren Moore's "Office at Night" gives readers a glimpse into the painting of the same name via a young secretary's experience in New York as she tries to make ends meet without blatantly coming on to her boss. Joyce Carol Oates is as terrifying as ever as she relates the story of "The Woman in the Window," based on Hopper's nude Eleven A.M. The kept woman waits, naked but for a pair of flats, at the window, entertaining murderous thoughts and possible alibis.

Robert Olen Butler begins within the painting Soir Bleu for his short story, naming the clown in Hopper's cafe scene, along with the arresting young woman in the center of the piece. Kris Nelscott takes inspiration from the date as well as the subject of the 1931 painting Hotel Room, using the failure of the national banks and the reality of segregated America to tell the story of an empathetic woman of means at the time.

Michael Connelly takes on perhaps the most famous Hopper painting, Nighthawks, with a private investigator surveilling a young woman looking to the Hopper painting itself for inspiration. Jeffery Deaver's "The Incident of 10 November" uses Hotel by a Railroad as a picture-perfect illustration of how a scientist captured by the Russians is able to escape his imprisonment and forced nuclear research using guile and superb acting ability, as told from the perspective of the Russian military officer charged with keeping the scientist in the motherland.

Other entries in this collection are more fantastical, less tethered to reality. Nicholas Christopher paints a word picture based on Hopper's Rooms by the Sea in which a young heiress, Carmen, discovers the supernatural truth behind her long-lived mother and the family's ever-loyal butler, Solomon Fabius, who finally tells the young woman about her true family origins. Craig Ferguson's "Taking Care of Business" uses Hopper's South Truro Church as the backdrop for a bit of a ghost story, itself anchored by the church, its congregants and a preacher's fondness for marijuana.

In Sunlight or in Shadow shows off exceptional talent with 17 superb short stories based on superlative Hopper paintings--inspired pairings of artist and writers. --Rob LeFebvre