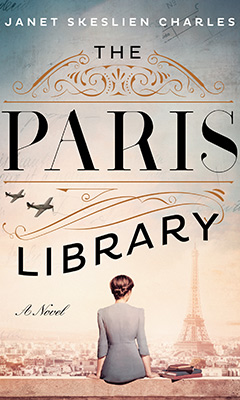

The Paris Library

by Janet Skeslien Charles

Fresh out of library school, Odile Souchet is thrilled to land a job at the American Library in Paris. Intelligent and ambitious, she has a deep love for the Dewey Decimal System, and thinks of the numbers constantly: " 'How would Dewey classify this lunch?' Rémy asked. 'That's easy--841. A Season in Hell.' " Odile is immediately enamored of her new workplace and its cadre of international borrowers and researchers. She comes to know and admire her fellow staff members, especially Miss Reeder, the library's sharply intelligent, imposing directress. But as the shadow of Nazi occupation looms ever larger over Paris, Odile and her new compatriots--not to mention the books they love--are inevitably caught up in the darkness.

In her second novel, The Paris Library, Janet Skeslien Charles (Moonlight in Odessa) weaves Odile's story together with that of 14-year-old Lily Jacobsen, growing up in Montana in the mid-1980s. Reeling from the loss of her mother and her father's remarriage, Lily finds herself adrift: overlooked at school, out of place at home. Intrigued by her reclusive elderly neighbor, Lily talks her way into Odile's house and begins asking questions. Though Odile, now a widow, has long been used to solitude, she and Lily strike up a friendship that flourishes with their French lessons and their shared love of the books in Odile's personal library. The connection between the two, as different as they are, will touch them both in a deep way.

On the surface, Odile and Lily--not to mention their respective historical moments--seem quite different. Odile, both in her younger and older incarnations, is elegant and dryly witty; Lily struggles with teenage awkwardness and has trouble articulating her emotions. But both regularly deal with jealousy and comparing themselves to others: in Paris, Odile envies her friend Margaret's elegant gowns and feels threatened by the affection her brother, Rémy, shows to his sweetheart, Bitsi, who is one of Odile's fellow librarians. Lily is intimidated by queen bee Tiffany, who always has the latest fashionable clothes and makes cutting remarks, and she fears being left behind by her best friend, Mary Louise, who is discovering boys. By the time Odile meets Lily, she is able to explain a bit about the corrosive nature of jealousy--but Odile is also hiding a secret, the revelation of which will force Lily to rethink what she has come to believe about her new friend.

Charles's narrative shifts back and forth between Paris and Montana, bringing in Odile's perspective as well as that of of her friend Margaret, a lonely Englishwoman who seeks out the library as a place of refuge and friendship. The library is full of other vivid characters, including two elderly gentlemen--one French, one English--who regularly spar over the contents of the daily newspapers, but harbor a deep respect for one another. When the Nazis begin eyeing the library's collections as potential acquisitions, Odile and Margaret, along with their colleagues, begin sending books to soldiers at the front and making plans to keep other materials safe from the occupying army. Even as the net tightens on the people of Paris, Miss Reeder and several other librarians, including Odile, refuse to leave. Her colleagues' quiet heroism makes a deep impression on Odile, and, nearly four decades later, on Lily.

Both narrative strands dig under the surface of events to explore things left unsaid. Odile's brother, Rémy, sends letters from his prisoner-of-war camp, and she is able to send letters back, but they both leave certain information out so as not to worry each other. Odile and her parents barely discuss Rémy's situation, though all of them are worried about him. Odile's beau, Paul, a young policeman who works with her father, is increasingly troubled about what he sees on the job, but feels caught between his duty to the police department, his affection for Odile and the increasingly brutal treatment of Parisians by the occupiers. Margaret, the isolated wife of a diplomat, struggles to express the range of emotions she feels at being far from home and not quite fitting in anywhere.

In the Montana narrative, Lily has only a vague comprehension of the Cold War and political events, but she understands that faraway foreign policies do have an effect on her life. Closer to home, she and Ellie, her father's new wife, tiptoe around one another, neither quite sure how to bridge the awkwardness created by Ellie's presence and her mother's absence. And although Lily and Odile are able to communicate directly on some topics, they, too, are sometimes unable to say what they feel or ask the questions they harbor. Charles treats her characters with deep compassion, but all of them are eventually forced to face the consequences of their actions, and do what they can to move forward with grace.

A love letter to libraries, a testament to courage under fire and an honest exploration of complex friendships, The Paris Library is a treat for book lovers, Francophiles and anyone whose life has been changed by a dear friend. --Katie Noah Gibson