Dear Child

by Romy Hausmann

German author Romy Hausmann's chilling English-language debut, Dear Child, begins where other abduction thrillers end: with the abductees having escaped. But they are far from being free, and Hausmann keeps readers captive until the last sentence.

When Lena Beck was a 23-year-old student, she went missing in Munich after attending a party. That was 13 years ago. In the present, near the Czech border, in Cham, a woman runs out of the woods one night and is hit by a car. She has no ID or personal effects on her, but right behind her is an eerily calm 13-year-old girl. When paramedics arrive, the girl tells them her name is Hannah and her mother is Lena. Hannah even knows her mom's blood type.

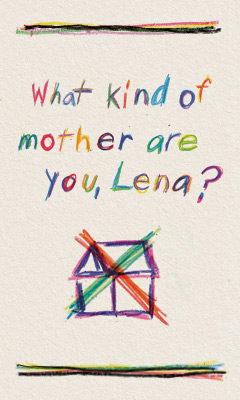

While waiting for Lena to undergo surgery at the hospital, Hannah is looked after by Sister Ruth, who attempts to retrieve emergency contact info from Hannah. What's her father's name? Family surname? Phone number? Address? Where was Lena running from?

Hannah whispers, "Nobody must find us."

When Sister Ruth asks her to elaborate, Hannah says, "[Mama] wanted to kill Papa by accident," and tells her that Hannah's younger brother, Jonathan, is back at their cabin in the woods cleaning stains from the carpet. He was scared of the noise. What noise? "What it sounds like when you bash someone's head with something. Bam!"

Certain something is very wrong, Sister Ruth notifies the authorities, who eventually call Lena Beck's parents, Matthias and Karin. After 4,825 days, they cannot believe the police have found Lena, injured but alive.

Matthias and Karin race to Cham in the night, and encounter a crushing surprise at the hospital. But they also catch sight of Hannah, who's the spitting image of Lena as a teen. The girl is being remanded to a childhood trauma center and, apparently, Matthias and Karin also have a grandson, who's been found at the cabin--along with the body of a man with his face bashed in. The kidnapper is dead, and the nightmare is over for his victims. Or is it?

Comparisons to Emma Donoghue's Room are perhaps inevitable, but by starting the novel with the abductees' escape, Hausmann keeps readers wondering where the story goes from there, as it travels down mysterious and surprising paths. Chapters alternate between the points of view of Matthias and the former captives, with flashbacks providing glimpses of what happened inside the cabin. Scenes of cruelty are horrifying but not graphic; most are narrated by Hannah, who doesn't fully understand the significance of the adults' actions.

Hannah's voice is the most striking, and Hausmann captures it perfectly. Born in captivity, the girl is both highly intelligent and achingly innocent, her view of the world entirely shaped by a cruel man. Her impeccable politeness has a sinister effect, making readers question what's beneath the unruffled patina. She draws disturbing pictures, in art therapy and to pass the time, observing that she needs the crayon in carmine red to illustrate fresh blood, that claret's "fine for old blood, and for really old blood the brown crayon is best." Her matter-of-fact revelations raise fresh questions in a case thought to be closed.

And Hannah has no patience for people without manners. When her little brother becomes catatonic after he's given pills at the children's psychiatric center, Hannah thinks, "I don't like his stupid eyes" and "it's making it harder for me to love him." After all, he must say hello when he sees her and not hit his head on the table while eating. She starts distancing herself from Jonathan, which makes his plight even more heartbreaking. At least inside the cabin, the boy felt loved by his sister and mother.

In contrast to the children's reactions, Matthias is consumed by rage. Rage at the fact that he couldn't prevent Lena's abduction, that he still doesn't know all the horrors she suffered at the cabin, that he now might have no control over his granddaughter's care. He's faced with questions from his wife and from Hannah's doctors: How can he provide a "normal" life for someone who feels safest locked up in a cabin? The whole ordeal hurls Matthias toward a startling self-reckoning, with Hausmann showing how someone driven by love might inflict as much damage as someone who sets out to harm.

The author also explores the notions of imprisonment and freedom, how neither is tied to four walls and physical space. After moving back to her own place, the woman who fought and escaped from her abductor realizes she's still a prisoner. She keeps her doors locked and shuns company, allowing only her former girlfriend to visit. Her fears, Matthias's savior complex and Hannah's desire to return to the only home she knew collide in a white-knuckle climax. And just when readers think it's okay to exhale, the final note of hope--of one woman's determination to find beauty beyond boundaries--will take their breath away. --Elyse Dinh-McCrillis