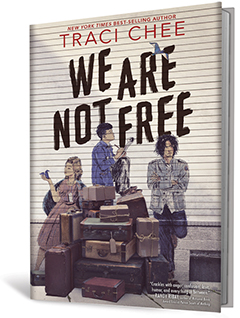

We Are Not Free

by Traci Chee

In a mesmerizing genre-switch, YA author Traci Chee moves from the fantasy worldbuilding of her acclaimed The Reader trilogy (The Reader; The Speaker; The Storyteller) to World War II historical fiction, with unforgettable results, in We Are Not Free. As a fourth-generation Japanese American, Chee gets personal, affectingly infusing her own family's stories into the experiences of a tight-knit group of Japanese American youth who grew up together in San Francisco's Japantown. Chee gives distinct voices to the 14 friends through a precisely structured novel told in 16 compelling interlinked stories that follow the teens through their incarceration in internment camps to the scattered restart of their postwar lives three years later.

Following the December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which led to the forced removal and imprisonment of more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry--the majority of whom were U.S. citizens. Uprooted from their homes, mostly from the Pacific Coast states, and expelled from their communities, Japanese Americans were sent without cause to prison camps scattered throughout the western and midwestern states for the duration of WWII and, in some cases, for months past war's end.

We Are Not Free opens and closes with the book's youngest narrator, 14-year-old Minnow, a contemplative observer who records his surroundings in detailed drawings, as all that was once familiar implodes rapidly and irreparably around him. His middle brother, Shig, reluctantly prepares for their inevitable expulsion from home as he bears witness to entire households desperately up for sale while "bargain hunters descend... offering ten cents to every dollar's worth of stuff."

Shig's 16-year-old girlfriend, Yum-yum, describes the journey to the Tanforan Racetrack, transformed into a temporary detention center in San Bruno, and her family's months-long incarceration in filthy horse stables. They will remain fatherless throughout the war, since the FBI took him to parts unknown just after the bombing for being "a businessman with contacts in Japan." By September 1942, more permanent assignments are announced, sending many of the teens and their families to Topaz, Utah. Hiromi-now-Bette narrates, introducing herself at camp with her middle name, because--ironically--"Bette is so much more appropriate for a modern American girl like me." The details of everyday camp life include making homes in barracks, surviving food poisoning and supply shortages, negotiating parental relationships, planning dances, navigating romances and more. All are revealed by angry Frankie, whose father was a U.S. WWI veteran; Stan, who dreams of going to college; Aiko, who begins to assert her independence from her stifling parents; and Yuki, whose softball prowess gives--then snatches away--a brief moment of freedom.

As the politics of war invade the camp, families become divided over the so-called loyalty questionnaire's problematic Question 27, "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?," and Question 28, "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?" Allowed to answer only "yes/yes" or "no/no," the incarcerees become further trapped in an impossible situation: a demand to risk lives (especially of young adult sons) while families remain imprisoned, or become completely stateless.

Stan's and Kiyoshi's families disclaim loyalty, causing their removal to Tule Lake. Minnow's oldest brother, Mas, and their friend Twitchy ship out to the European front in the segregated all-Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became the most decorated military unit of its size in U.S. history. Keiko gives voice to what happens at home as still-incarcerated families await news of their loved ones. When tragedy strikes, "all of us"--the survivors, anyway--must figure out ways of "knitting together in the places where we were broken... finding each other in the darkness... holding fast" and, once more, beginning to "breathe at last."

Chee's effortless amalgamation of history and fiction becomes spectacular storytelling that is both illuminating and immersive. "This history is my history," she explains in an author's note, specifically acknowledging the Nisei (second-generation) relatives she interviewed, including her great-aunt whose "I am not free" mantra while incarcerated at Tanforan gave Chee her title. Although "these fourteen perspectives are a mere fraction of what this generation went through," Chee manages to create a remarkably streamlined narrative, weaving together perspectives, reactions, reports and geographies. Chee makes the highly effective literary decision to forgo translating most of the Japanese words her characters insert into casual conversation, asking readers to find understanding through inference rather than interruption. (She even leaves untouched the Japanese hiragana script used in a letter from one teen friend to two others.) In electing not to translate, Chee minimizes the foreignness, instead emphasizing the fluid hybridity of her second-generation characters. This decision brilliantly displays how very ordinary the teens--and their dual identities--are.

Prefacing almost every chapter with a stark visual, including Minnow's notebook sketches (drawn by artist Julia Kuo), newspaper articles, official government announcements, black-and-white photographs, postcards and telegrams, Chee provides a wealth of edifying context to her already exceptional text. Exquisitely rendered, Chee presents what should prove to be a significantly honored addition to American historical fiction. --Terry Hong