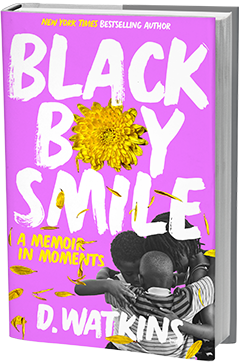

Black Boy Smile: A Memoir in Moments

by D. Watkins

In Black Boy Smile: A Memoir in Moments, D. Watkins moves into new, vulnerable territory. Watkins wrote about growing up in east Baltimore in The Cook Up and The Beast Side. Now, in Black Boy Smile, he dissects what he calls "the lie": codes of Black masculinity that forced him into stoic silence in order to survive his upbringing. In his new memoir, Watkins practices the opposite--he shares traumatic memories of sexual abuse and violence as well as ways in which "the lie" inhibited his growth and happiness. Through it all, his love for the people of east Baltimore shines through, and Watkins's story is ultimately a hopeful, redemptive one. Black Boy Smile feels radical in its openness and in its vision of a Black manhood that does not require bottling up feelings of pain or joy.

The subtitle gives a clue to the structure of the book. Thanks to its short, digestible chapters, it reads like a true collection of memories. In a roughly chronological sequence, Watkins recalls a childhood plagued by violence, the collateral effects of the drug trade, and feelings that he didn't know how to process or share with anyone else. He devotes multiple chapters to his time at a nightmarish camp where the children were forced to fight each other and the tyrannical counselors kept most of the food for themselves. Throughout, Black Boy Smile maintains its focus on Watkins's emotions. While his father drives him to the camp, Watkins lies and tells his father that he's not afraid. He writes: "I was raised in an environment where fear was lied about, even if you're nine years old.... The people I respected taught me that fear was the worst thing a man could be." After camp ends, on the drive home, Watkins sticks to the lie, telling his father: "Camp was alright. It was cool."

To be clear, Black Boy Smile is far from a parade of traumatic memories. One chapter follows a trip with his father to buy shoes that ends with them stuck in a rainstorm; his father urges him to cry so they can finagle a car ride from a "big-haired, extra blonde white woman." Watkins's colorful prose delivers humor and attitude at every turn, particularly in the vivid descriptions--"the stumpy teacher, dressed in three different shades of JC Penney brown"--and in the way Watkins and his friends chat and joke with each other. Some of the most memorable conversations take place between Watkins and Tweety Bird, his friend's girlfriend, whose "heart was bigger than the whole side of east Baltimore." In one tragicomic conversation, Watkins reveals how he used to encourage girls to leave after sex by turning up the air conditioning: "All Black girls from Baltimore are anemic, so the cold works," he says, while Tweety reacts in horror. Their playful, teasing exchanges circle around the deeper truth of Watkins's transactional relationships with women, which in turn hints at the loneliness he tries so hard to bury.

Watkins soon finds himself selling drugs and earning a great deal of money, but cars and piles of shoes can't prevent him from becoming increasingly miserable. The first hint of a brighter future comes through books. Reading Sister Souljah's The Coldest Winter Ever ignites a passion for reading that helps change his path; he goes on to attend college, earn his MFA and pursue a career in writing. According to Watkins, "being Black in an MFA program is kind of like being white in the Black Panther Party," and the resulting culture clash leads to some of the book's funniest, most cutting sentences. But even though his classmates seem to have an easier time relating to Harry Potter than to "a Black boy from Baltimore," Watkins finds that compared to what he'd been through, "dodging the narrow-mindedness of privilege was easy." Writing becomes something he pursues with a single-minded determination, far removed from his lucrative but hollow life dealing drugs.

Black Boy Smile is a powerfully redemptive work because Watkins finds more than a new career; he finds a new way of being, one that requires unlearning "the lie" and so many of the lessons of his past. In its place, he finds love in a relationship markedly different from the cold arrangements that he once preferred. It takes time, and he has to learn to let someone in, but ultimately love succeeds in shattering "the steel wall that housed my emotions." A particularly moving passage describes Watkins's journey to becoming a father, prompting him to consider the unique challenges his daughter will face as a Black woman. At the same time, though, Watkins's story is one of learning and healing, and his determination to pass on the lessons he's learned--to make sure that his daughter is raised in a joyful environment--ensures that the book ends on a profoundly hopeful note. --Hank Stephenson