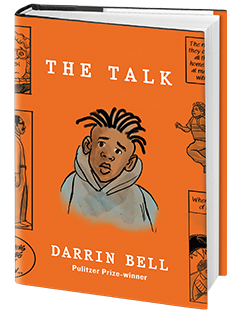

The Talk

by Darrin Bell

In his first memoir, The Talk, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Darrin Bell delivers an intimate, incisive depiction of coming of age as a Black boy in the United States. Since his work was first published in 1995, Bell has made readers think and feel, through his editorial cartoons and comic strips about politics, family, culture, and current events. This full-length graphic memoir about growing up, building a career in the public eye, and raising a family is no different. Bell begins and ends the book with "The Talk," the conversation during which parents teach their Black children about anti-Blackness: why the people and institutions they encounter will treat them differently, and how to try to stay safe in a racist world.

Bell opens The Talk with powerful imagery that he revisits in later chapters: Darrin and his brother encounter a pack of aggressive neighborhood dogs; he is told they'll leave him alone if he stands still and puts his hands out for them to sniff. This danger stalks him through his life. When Darrin is six years old, he wants a water gun to play with. His mother tells him no, and sits him down to have The Talk. Later, he sneaks out to play with the green water gun his mother eventually bought him. That night, he has a chilling encounter with a police officer as he's bent over a puddle, refilling the neon green toy. He holds his hands out so the officer--face melding into that of a dog--can see they're empty.

In a style quite different from Bell's syndicated editorial cartoons and comic strips, The Talk is illustrated with inks primarily washed with deep blue or tan. Color is employed strategically: the dark blue-gray initially seen on the dogs haunts Darrin through the pages, while occasional full-color images attract the eye. When Trayvon Martin is murdered, for example, the word "thug" is written in red over white text that reads "child." Color is also present in recurring images that tie the narrative together. In addition to the dog motif, close-up panels featuring eyes are a frequent feature. Usually in bright color, the images reflected in Darrin's eyes are an effective shorthand. Sometimes they call back to a previous scene, sometimes they're as simple as a flashing red siren. In one panel sequence, readers see several racist events in the eyes of former president Donald Trump.

Bell has mastered the art of distilling powerful messages into just a few panels. In one scene, Bell and his college girlfriend are pulled over in Berkeley while headed to dinner in a rental car. The author gives the officer the same face as the officer who confronted him when he was six years old:

"He asks us how we got into Cal. I tell him my high school G.P.A., my AP test scores, even the topic of my essay. He asks my major, and he asks how I could afford to pay for this rental.

"When I tell him I'm a cartoonist for the Daily Cal, and I've been published in the LA Times, he scoffs in disbelief. When I tell him I also work security for Cal Performances, he asks my supervisor's name. I tell him with no hesitation.

"That's when he tells us we're lucky we got in before Prop 209. He holsters his gun.

"I hadn't even noticed he'd been holding it."

Thirty years later, the incident is etched in Bell's memory. The danger and trauma of this traffic stop is memorable but not singular: it's the experience of driving as a Black man in the United States.

With the insight of an editorial cartoonist, Bell takes readers through many of the big events in the United States over the last few decades, including the 1991 beating of Rodney King, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, legalization of gay marriage in 2015, and the Covid-19 pandemic. He also focuses on some that were closer to home for him, such as the passing of the anti-affirmative action California Prop 209 the officer refers to when he's pulled over.

As Bell curates a collection of moments for the reader, he chooses many that don't cast him in a flattering light: he wants readers to know that not only has he experienced prejudice, he's been complicit at times. A white teacher tells young Darrin he's "one of the good ones," and while he interrogates what that means, he ultimately takes it as a compliment. He judges his mother for her "scenes," cringing as she takes a racist teacher to task. He even draws an editorial cartoon after the bombing of the Twin Towers that portrays the hijackers looking exactly like Osama bin Laden; a mother of a Sikh boy writes to Bell about the fallout of that cartoon, and Bell stops his editorial cartoons for two years.

Prejudice is so pervasive it's absorbed by everyone, even those who experience mistreatment. Bell assumes readers know objectively that racism is wrong, but not necessarily the bone-deep impacts of the daily, lifelong experience of a boy on the receiving end. This is a depiction of one man's journey to unlearn the Black exceptionalism programming installed in him by society and to find his authentic voice in the process. His confusion, frustration, and fear are palpable, but so is his determination.

Darrin has a life: he builds a career, falls in and out of love, has children. And then, no matter his achievements, he has to give his six-year-old son The Talk. Herein lies the heart of the book: it doesn't matter who Bell is, who his son is, who his beloved wife and daughter are, he still has to tell his son that his world will see him as a threat.

The Talk speaks to a wide audience. It's funny: Bell learned early to use humor as a form of self-defense. It's a how-to guide: Black families will see themselves in the pages and be able to discuss it with their children. It's a compelling life story and a letter to his son. For readers of Between the World and Me and graphic memoirs like Fun Home, The Talk is an essential conversation. --Suzanne Krohn