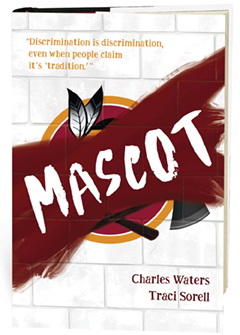

Mascot

by Charles Waters, Traci Sorell

In Charles Waters and Traci Sorell's transformative and compelling novel-in-verse, Mascot, six eighth-grade Honors English students with different backgrounds and beliefs debate the issue of Native mascots in class, while the same discussion plays out in their community. This middle-grade novel makes a complicated, emotionally charged issue accessible to a broad audience, and the evocatively written narrative is told through multiple, distinct perspectives.

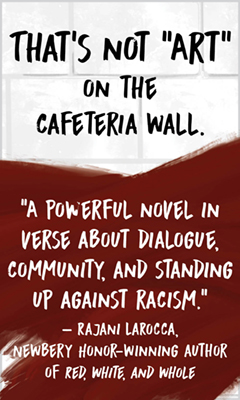

Callie Crossland, a Cherokee Nation Citizen and descendant of enslaved Africans, is a recent transplant to Rye, Va., outside Washington, D.C. She makes it clear on one of her first days at Rye Middle School that the painting on the cafeteria wall depicting a "copper-toned, muscled, loincloth-clad, tomahawk-wielding caricature with Rye Braves Rule" is not "art." Franklin Keys is a Black student who believes high school football is the "backbone" of the community, and the football players are the "gladiators" of the town. Indian American Priya Bhatt, whose father is a White House journalist, reluctantly covers the Rye Braves--which, in her words, are "centered on objectifying a culture"--for the middle-school newspaper. Sean McEntire, a sixth-generation Rye resident and white, isn't much of a talker but loves how the Braves bring people together. Tessa Ostergaard, a white student who has been homeschooled for most of her education, is "privileged, ponytailed, and super sad about the way the world is going." And Salvadoran immigrant Luis Flores thinks the mascot is about "pride" and "belief in one's self." Franklin, Sean, and Luis are diehard Rye Braves fans--"Braves power, baby!"--while Callie, Priya, and Tessa see the sports program as "chants and gestures that show no honor for Native people... just racism."

The students have mixed emotions about their latest assignment: a "Persuasive Writing and Oration./ Subject: Pros and Cons of Indigenous Peoples as Mascots." Their teacher Ms. Williams, "much-needed melanin in a sea of white teachers," has paired up students and chosen which side they'll argue. Callie is paired with Franklin to argue in favor of the mascot. Franklin begins researching the history of mascots to "school Callie and her woke nonsense," but the harder he tries to disagree with Callie's view, the more he realizes she may be right. Tessa, also tapped to argue pro-mascot, can't help herself and bombards her partner, Luis, with anti-mascot information. Overwhelmed Luis thinks people are being too sensitive about this topic, and he's tired of it. Sean and Priya are tasked with arguing against Native mascots, but Sean fails to see the negative impact on Native youth, choosing to center himself instead--"I'm Irish. I'm not offended by the Boston Celtics...."

Meanwhile, at the high school, students are mobilizing to protest the school district's mascot, and collecting signatures to petition for it to be changed. Callie, Priya, Tessa, and Franklin create social media posts and flyers to help, gathering over 600 student signatures and more than 900 from the community. They submit the petition to the school committee right before winter break and hope that spring semester will bring the much-needed change they're fighting for.

A key theme in Waters and Sorell's Mascot is the importance of seeing oneself positively represented in media. Ms. Williams provides her students with books, poems, and short stories about and by Black and Brown people so that they can see themselves and each other. Waters (Can I Touch Your Hair?) and Sorell (We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga) extend this theme with their choice to tell the story from multiple viewpoints. The students in Ms. Williams's eighth-grade English class, with their varying backgrounds, beliefs, and reactions to Indigenous peoples as a sports mascot, function as a microcosm of U.S. society. The story is told through vignettes, each character (including Ms. Williams) getting space to tell it from their perspective. Many points of view are represented: a Native person who feels smothered by the tomahawk chopping, chanting, and yelling; a Black person who is proud of their Blackness even in the face of other students calling him an "Oreo"; a poor white person who doesn't understand how they could be considered privileged when their parents "don't own squat"; a well-meaning white "ally" who does more harm than good. The varied first-person perspectives provide insight into both sides of the argument while also developing fleshed-out characters with distinct voices.

Mascot is not only about human rights and Native autonomy--it's also about low-income kids who shoulder the burden of their parents' financial struggles, lonely kids who wish they had a friend to spend time with, immigrant kids pressured by their parents to succeed, and teachers who face criticism and pushback from colleagues "wrapped up in their privilege." The authors' choice to use verse instead of prose to tell these stories makes the title accessible and gives Waters and Sorell the opportunity to creatively utilize white space, language, and sentence structure. Repetition, varied line spacing, and single-word sentences ("Mascots./ Deadlines./ Assignments./ School's stressful.") are all ways the authors create tension and express emotion without cluttering the plot with too many details.

Waters and Sorell bolster their well-researched narrative with facts about real-life sports teams' stereotypical mascots and the effects they have on both Native and non-Native people. Backmatter includes glossaries of Cherokee and Salvadoran Spanish words, as well as more information about mascots and resources for further action.

Mascot, with its multilayered, insightful narrative and diverse voices, reveals the nuances of an emotionally charged topic in a passionate, accessible way. --Lana Barnes