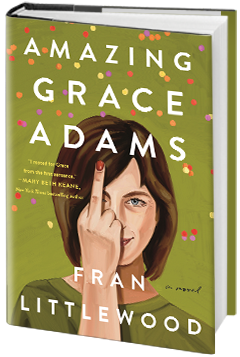

Amazing Grace Adams

by Fran Littlewood

Fran Littlewood's propulsive debut, Amazing Grace Adams, is a wildfire of a novel, wickedly hot and demanding attention. The book opens with 45-year-old Grace Adams stuck in traffic, desperate to escape the summer heat, her aging, overheating body, her fear of losing everything. Then Grace does the unthinkable, abandoning her car in traffic and embarking on an odyssey toward the one thing she hopes to salvage from her shattered life: her daughter, Lotte, on her 16th birthday. Some might call what follows the worst day of her life, but as the story of Grace and her broken family unfolds, it becomes clear that the events of this day have their roots planted many years earlier, and she has every right to the rage that spills out of her.

Littlewood builds the narrative in three distinct strands, each pulled to a precise tautness, and weaves them together into an unforgettable story about a woman who has had enough. Littlewood creates thin layers of narrative, moving between timelines with ease, revealing the worries and joys and griefs that make up a life. That opening scene is familiar and awful, full of leering men and car horns and roadwork and, always, the heat. It is hot outside, insufferably so, but Grace is also boiling internally, both emotionally and physically, due to perimenopause. The tension in the scene builds, and readers wonder why Grace "can't be late, not today, there's just no question" and what will happen after she whispers, "Deal with it" and walks away. Grace's triumph in that moment is undercut by the page turn, the abrupt shift from the present day to four months earlier, when Grace begins to understand her life may be unraveling. A few pages later, the timeline shifts again, taking readers back to 2002 and the moment when 28-year-old Grace meets Ben, a fellow linguist who will become her husband.

It's to Ben's home that Grace is headed on this fateful day, the flat in North London that he moved into after telling her he didn't want to be married any longer. It's where their daughter, Lotte, has retreated as well, and the reason for these estrangements will gradually unfold. Both relationships are written tenderly and with an attention to detail that renders both the past and the present rich and fully inhabited. But as the events that started four months earlier creep closer to the present, and readers learn more about Lotte's school absences and social media activity, and the secret relationship Lotte appears to be having, it becomes clear that Grace and Lotte are wrestling with more than typical adolescent attitude and mother-daughter disagreements. There is so much under the surface of this story; the way Littlewood teases out each vital detail is so skillful that even savvy readers will not expect the different turns the narrative takes.

Despite the drama of Grace's very bad day, it is the quiet moments of love and aging and family and loss that make this novel remarkable. When Grace texts her daughter, who is upstairs in her room--"because this is the way they do things now"--or when she watches Lotte dance and remembers "something she'd forgotten she knew. She feels it bodily and its force shocks her. That giddy up-and-out-of-herself high that comes from the music, the dancing, the intensity, the promise. It's like she can smell it, taste it, and why hasn't she realized before that it is gone?... It isn't that she's jealous, not exactly, because it fills her up that her daughter gets to feel this way. But there's a grief in her too, for this thing she hadn't known she'd lost." Littlewood gives voice to Grace's most ordinary thoughts and the often taboo feelings surrounding midlife, and in so doing, she has created what could be called Everywoman, but one with few restrictions. Grace gives herself permission to feel all the things a proper adult isn't supposed to express: desire, embarrassment, frustration, and, of course, anger.

Grace's anger is the oxygen to her flames, the thing that overruns her senses and turns her into the most frightening version of herself. When a kind older woman offers unexpected help, Grace admits, "And sometimes I have so much rage it scares me," and the woman responds, " 'That's not rage, darling. That's your fear, your grief exploded.' She pinches her fingers together, then springs them apart so that her empty hands are stars. 'You do the best you can. We all do.' " Like all of us, Grace is just doing the best she can. This unhinged day is a mess, a raging fire of emotion and impulsivity, but it is not the worst day of her life. There are worse things than this, and she has survived them, so there is hope. Even as Grace's world burns, readers will be left gasping, laughing through tears and hoping she will be the phoenix emerging triumphant from the ash. --Sara Beth West