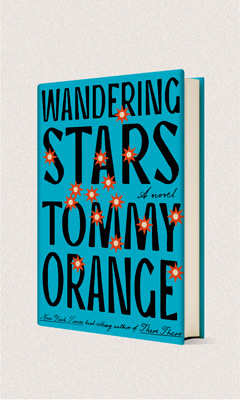

Wandering Stars

by Tommy Orange

This deeply expansive portrait of a Native American family and those inextricably linked to it is Tommy Orange's masterful follow-up to the PEN/Hemingway and American Book Award-winner, There There. Part prequel, part sequel, Wandering Stars traces a family line from a boy who escapes the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre to his descendants in the aftermath of the powwow shooting that takes place in There There. It is an immersive and stunning saga about individuals endeavoring to survive and to live.

Orange, as he did with There There, begins Wandering Stars with a nonfiction prologue, this one about the genocidal campaigns against Native Americans, about children forced into boarding schools to be taught that their way of life was wrong, about their descendants being told they "weren't the right kind of Indians to be considered real ones." In so doing, Orange sets the stage for Jude Star's story to spill across time to Orvil Red Feather, who must continue living after being shot at the Oakland powwow.

The image of wandering stars connects these two distant relatives, both of whom become lost in addiction. The bullet shard shaped like a star inside Orvil might "wander," so it must be watched carefully. What it does instead is carve a hole inside Orvil that he fills with pills. Orange portrays that addiction deftly. Drugs grant Orvil a certain kind of freedom. While high, he plays music, for the first time fully immersed in what is happening. In school, he finds a self-certainty he previously lacked, an "easy-spread peanut butter, white-boy confidence." It's a feeling he doesn't want to lose.

His great-great-great-grandfather, Jude, turns to alcohol. He feels like the "wandering stars" in a Bible verse who are "twice dead" because he survived Sand Creek, was then jailed at a prison-castle, and upon liberation, had to change his name, which to him is "like dying again." Consequently becoming a heavy drinker ("alcohol I wished I just wanted but knew that I needed"), Jude wonders whether to believe in a second wind in life--a "part of you, hidden away in a true place, even from yourself, for when you needed it most." That belief carries him past drinking, past a job as chief of police "stopping any and all Indian ceremonies and rituals," and into fatherhood with a son, Charles, to whom he tells stories of his life. "Stories do more than comfort," Jude narrates, "They take you away and bring you back better made."

Perhaps Jude's second wind is also what fuels his descendants, because his great-granddaughter Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield embodies strength. She wants to go on living with her three grandnephews--Orvil, Lony, and Loother--and her newly sober sister "like [they've] been given a second chance and not like something's already been taken away from [them]" by the powwow. It is too positive an outlook for her, and Lony notices. He, who feels furthest of them all from being a "real" Native American, dreams of dominoes that he knows represent his family line--"all that they couldn't carry, couldn't resolve, couldn't figure out"--"coming to knock him down." He can make this better, he thinks, with his blood, which he is burying to see if it's magic because that same blood helped Orvil heal. "You have to trick yourself into believing," he tells his family. Loother, who sees how hard Lony, and everyone else, is trying, wants them all to chill out like he's trying to do. Go to school, spend time with his girlfriend, think about ridiculous things like robot takeovers--that's living. He knows this world is backward, but he likes living. The question is whether his family can all see their way to living, too.

Orange fills Wandering Stars with his signature musical prose and searing precision of language to tell a story about survival, belonging, and simply being human. It is also a story about story itself, about purpose. Jude Star's son Charles feels "muddied" from his parents "mixing their blood and making him. Surely there was a story he was a part of, that spoke to the purpose of his life?" Even moments from death, he wants to find it. Decades later, Charles's second great-grandson, Orvil, listens to his therapist explain that "we have to sound out our stories... frame and reframe them" to make our steps forward more purposeful.

This, Orvil finds corny, which Orange connects to authenticity, another theme woven throughout. An imprisoned Jude Star "perform[s] being Indian for the white people," dancing while they watch "with that strange mix of disgust and astonishment." Victoria Bear Shield wonders where she would be from if she were a "real Indian." Sean Price, whom Orvil befriends, bemoans his good looks, which get him treated superficially, denying him the "real experience regular-looking people got walking around in the world all regular." Being a real Indian isn't something Lony cares about, yet a powerlessness and heaviness move him to try in astonishing ways.

Orange captures with magnificent power his characters' experiences as Native Americans. Victoria wonders if her name came from a victory cry that her mother sounded after bringing "another Indian into a country that'd been doing its best to disappear [Indians] for hundreds of years." Her great-grandsons will come to think of themselves as time travelers: "Everyone only thinks we're from the past, but then we're here, but they don't know we're still here, so then it's like we're in the future." It is through these striking moments of clarity, and through his characters' drives to find fulfillment in life, that Orange has created in Wandering Stars a transcendent, multi-POV novel that beautifully humanizes a way of life that the powerful in the U.S. have been attempting to eradicate for generations. --Samantha Zaboski