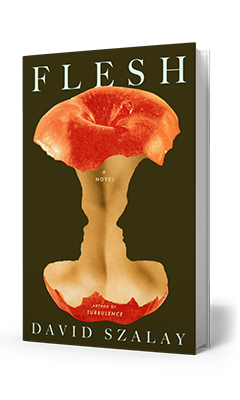

Flesh

by David Szalay

An oft-cited rule of fiction is that the protagonist should be active rather than passive, propelling the narrative forward rather than letting events dictate behavior; however, passive protagonists can yield captivating results. The great writer David Szalay understands this. From the couple at the center of Spring to characters in his linked story collections All That Man Is and Turbulence, Szalay has created figures who, if not always wholly acquiescent, are acted upon at least as much as they initiate. That's true of István, the Hungarian teenager whose serendipity brings him to the heights of wealth and power, only for tragedy to complicate his path, in Flesh, a brilliant novel that is as much about the immigrant experience as it is a cautionary tale about capitalism and the allure of eros.

As the title suggests, Flesh has a lot of flesh, although eroticism, none of it glamorous, is only one part of this multifaceted work. The story starts in the late 20th century, when István and his mother move to a new town in Hungary. At school, he eventually makes a friend, "another solitary individual," with whom he talks about sex. That friend brags of having had sex with a girl and tells István that the girl would be happy to extend the favor to him as well. That the meeting doesn't go as planned is the first in a series of encounters that will shape István's worldview and drive his actions--or reactions--throughout the novel.

From the book's earliest scenes, Szalay dazzles with the matter-of-fact prose style already familiar to readers of his work. Sentences are short and punchy. ("The three of them just stand there. The girl looks at István again. He doesn't look at her.") Many paragraphs are only one line long. Dialogue is quick and clipped, with István and others often responding to circumstances with a simple "Okay" or "Yeah," further reinforcing an unassertive approach to life.

This stylistic choice is simple and propulsive, a sleight-of-hand that makes characters, István in particular, relatively passive while giving the novel its forward energy. That technique serves to emphasize the rawness of subsequent sexual encounters, the next of which is with a 42-year-old married woman who lives in his building. István's mother tells him to help the woman by accompanying her to the grocery store. It will come as no surprise that the woman asks István to do more than carry grocery bags. Their secret tryst continues until a tragic accident forces its abrupt end and also an end to István's time in Hungary.

Odd jobs follow, from a stint in the army to one working in a wine cellar, before István emigrates to London and becomes a doorman at a strip club. Then, more serendipity: as he walks back to his flat one night, he sees an old man bleeding on the street. István calls an ambulance and rides with the man to the hospital. The man, it turns out, runs a private security agency and invites István to work for him. Soon, István is raking in a handsome salary, albeit after the man teaches him how to act and dress around high-toned clients. "You need some grooming," the man says, and István obliges.

That's just the beginning of István's upward trajectory. Years later, he becomes the personal Mercedes driver to the wealthy owner of a large Swedish electronics firm, his much-younger wife, and their young son. After the man dies, István marries the now-wealthy widow, and ascends to a more prominent position in business than any of his previous stints could have suggested. But that ascendance is part of a package that will include jealousy, political intrigue, allegations of financial chicanery, and personal tragedy.

Astute readers of literary fiction who enjoy thoughtful stories, stripped-down prose, unpredictable turns, and a counterpoint to traditional narratives about the immigrant experience will find much to savor in Flesh. As with any good book, the themes emerge gradually. What starts out as a seemingly simple tale of one man's wayward journey becomes a profound examination of the perils of capitalism, the appeal of escape, and the chasms that often separate people, whether they're stepchildren who hate their stepfathers or English people who detest immigrants.

Many of Szalay's books have titles that can be interpreted in several ways. There are the ironic titles, like All That Man Is, with its implicit critique of masculinity. Then there are titles like Turbulence, with its portraits of the disordered lives of air passengers on a series of flights. Flesh is another example. The obvious allusion to carnal pleasure also has its Shakespearean side, with some characters keen on revenge and exacting their pound of flesh. That's only one of the many subtleties and layers of complexity readers will find in this rewarding work from one of the most original authors in English letters. --Michael Magras