At BookExpo America,

|

| photo: Brady Hall |

at the end of May in New York City, Neil Gaiman gave a talk provocatively titled "Why Fiction Is Dangerous." He noted that he had two books--Fortunately, the Milk

and The Ocean at the End of the Lane

--being published within two months of each other: one, a children's book with an adult narrator; the other an adult book from a seven-year-old's perspective. Gaiman recently paused during his cross-country U.S. tour for the books to answer a few questions about them (plus a few other things). Born and raised in England, Gaiman now lives in the U.S. with his wife, musician Amanda Palmer.

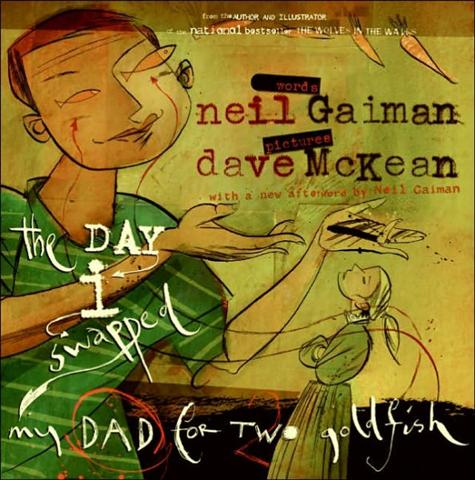

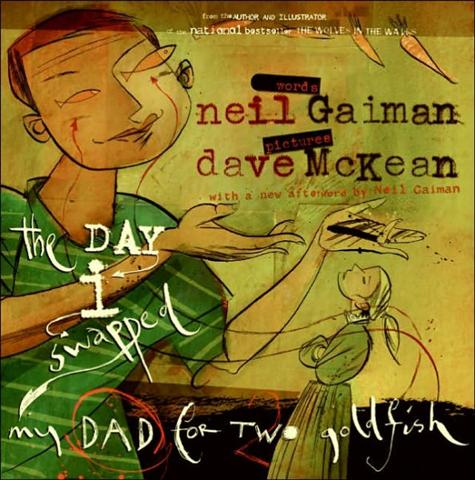

You've said you wrote Fortunately, the Milk to "redeem" fathers (our word, not yours) after The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish. Did you sit down to write a story for fathers? Or did you have the idea for Milk and then think, "Aha! This could be a story to make amends to fathers after Goldfish"?

I think I should try and pay more attention to my creative process because I'm genuinely not sure at which point I decided I was going to write a riposte to The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and it would be called Fortunately, the Milk and it would be about dads. But I do think that the years of looking at The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and going, "this is not--and it's not even not positive--it's not a good thing for parents," and "I should do something which at least shows the other side of the coin." I suspect that sitting in my head for many years was the starting point.

I think I should try and pay more attention to my creative process because I'm genuinely not sure at which point I decided I was going to write a riposte to The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and it would be called Fortunately, the Milk and it would be about dads. But I do think that the years of looking at The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and going, "this is not--and it's not even not positive--it's not a good thing for parents," and "I should do something which at least shows the other side of the coin." I suspect that sitting in my head for many years was the starting point.

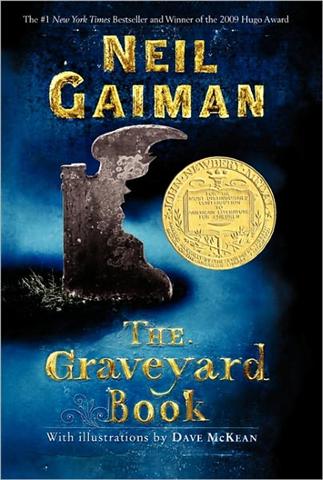

In The Graveyard Book, Bod finds a safe haven with the dead in the nearby cemetery; the nameless boy in The Ocean at the End of the Lane finds refuge with the Hempstocks, and the father in Fortunately, the Milk is aided by a stegosaurus and uses time travel to give his pursuers the slip. Do you think people often find refuge in places other than their biological families?

In The Graveyard Book, Bod finds a safe haven with the dead in the nearby cemetery; the nameless boy in The Ocean at the End of the Lane finds refuge with the Hempstocks, and the father in Fortunately, the Milk is aided by a stegosaurus and uses time travel to give his pursuers the slip. Do you think people often find refuge in places other than their biological families?

I think people find refuge everywhere, and I think that people make families as much as they are born into them. And I also think that there is something special and magic, sometimes, about those people who you somehow know you are related to by blood; Robert Frost's definition of home as the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in, comes to mind. And, of course, they do. In each of those cases you're looking at people who get to build families or get to be given safe places by families, and, yes, people do often get refuge in the most wonderful, strange and unlikely places.

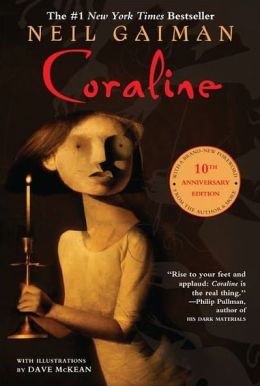

You also play with the idea of parallel worlds in both serious and whimsical ways--two milk containers from different time periods for the father in Fortunately, the Milk; in Coraline, there's the mirror button-eye family and the real family; in Ocean, there's the ancient world that the boy narrator is privy to, and the real world that only his family sees. What attracts you to this interplay between seen and unseen worlds?

You also play with the idea of parallel worlds in both serious and whimsical ways--two milk containers from different time periods for the father in Fortunately, the Milk; in Coraline, there's the mirror button-eye family and the real family; in Ocean, there's the ancient world that the boy narrator is privy to, and the real world that only his family sees. What attracts you to this interplay between seen and unseen worlds?

Probably my own personal belief that I don't get to see everything going on all the time. And the more you study anything, the more you realize there are huge unseen worlds going on at any point, whether you're reading books about quantum physics, where you learn that actually, more or less, we are all a bunch of hypothetical particles with an awful lot of space between us, or whether it's studying Henry Mayhew and London labor and the London poor and realizing all of these strange, secret worlds that would've been completely invisible to somebody navigating the streets of London. All worlds are 50% unseen.

No matter how much other characters assist your heroes, ultimately, they must find their own way. This is true in Fortunately, the Milk, when the father must save himself, and it's also true for Bod in The Graveyard Book, for the heroine of Coraline, and for the boy hero of Ocean. Why is that important to you as an author?

I think because for me the challenge as an author is in making somebody believable and letting them find their own way through things. I love though that in Fortunately, the Milk when the father does actually save himself and, quite possibly, the universe, all anybody is really impressed with is the milk, and they fail to notice it's him.

Let's pause here and reflect upon the fathers of your two recent books. In both Ocean and Fortunately, the Milk, the father is controlled by others. In Ocean, it's the otherworldly Ursula Monkton. In Fortunately, the father is at the whim of aliens, pirates, wumpires and Professor Steg. Why is that such a strong theme at this time?

Let's pause here and reflect upon the fathers of your two recent books. In both Ocean and Fortunately, the Milk, the father is controlled by others. In Ocean, it's the otherworldly Ursula Monkton. In Fortunately, the father is at the whim of aliens, pirates, wumpires and Professor Steg. Why is that such a strong theme at this time?

Oh, I would argue with this. I do not think the father in Fortunately, the Milk is controlled by anybody. He's definitely not at the whim of aliens, pirates, wumpires and Professor Steg, he is merely having an adventure with them. He is traveling with them and he is doing exactly what he set out to do, which is go to the shops and bring his children back some milk for their cereal.

I grew up with a father who tended to invent things and know things and talk about things and could absolutely have gone off into the kind of flight of fancy in Fortunately, the Milk. And my daughter, Maddie, when she read Fortunately, the Milk recently, said that when she got to the end, all she could think was that it sounded exactly like me. So, I think Fortunately is just very, very me. I'm not sure about in Ocean. It's left ambiguous whether the father is actually under the control of Ursula Monkton or not, and it would be worse if he wasn't.

In Ocean, there's a wonderful quote that harks back to a theme central to your Newbery acceptance speech. The narrator says, "Growing up, I took so many cues from books. They taught me most of what I knew about what people did, about how to behave. They were my teachers and my advisors." Was that true for you growing up, too?

Oh, absolutely. One hundred percent. My safest places were libraries, manned or unmanned by librarians. My teachers were books. They taught me to look out through other people's eyes, which is the most important thing that anything like that can do.

In Ocean, you never name the boy-man narrator. Yet the importance of naming is essential to the plot. Why didn't you give him a name? Is he Everyman? (In the same way that Bod is Nobody?) The children and their parents get no names in Fortunately, the Milk, either. Coincidence?

In Ocean, you never name the boy-man narrator. Yet the importance of naming is essential to the plot. Why didn't you give him a name? Is he Everyman? (In the same way that Bod is Nobody?) The children and their parents get no names in Fortunately, the Milk, either. Coincidence?

I don't know. I think part of it probably comes from when you are writing a first-person narrative, you don't necessarily think of people by names. I definitely can go through days, possibly go through weeks, without actually noticing that I'm Neil Gaiman. It's not something that I'm going to think about unless someone asks me my name or unless I have to write it. As far as I'm concerned, I'm me. And I loved the idea of a book in which names were enormously important and the act of naming was hugely important and names occur all through Ocean in all sorts of ways and shapes, and you'll find all of the children's stories, all of the important stories our hero runs into, have the names of women in their title, whether it's Alice in Wonderland or Iolanthe or the imaginary stories that I made up, the novels, the one about Sandy and stuff. But I love the idea that, especially when you're a kid, you can simply point, and you can say, "me," you can say, "my sister," and you can say, "my dad." The challenge in Fortunately, the Milk, was doing a narrative which had two different "me's" narrating. Both the father and the son get to tell the story, at the same time sometimes, and neither of them have names, other than their roles in the story.

Does your process differ if you're writing a children's book versus an adult book?

I'm not even sure what my process is and I've been doing this for 30 years. Normally, at some point, I will pull open a notebook and I will start writing stuff and that's always the beginning of the process. At the end of the day, if you're writing something that's novel length or is probably likely to turn into novel length, the process is going to consist of faffing around in the morning, getting your exercise done, maybe eating a light lunch and then going somewhere that you won't be disturbed, opening a notebook and writing. And, wherever that place is, that's going to be the process. It's going to be putting down the words.

What makes Ocean a book for adults, rather than for children?

What makes Ocean a book for adults, rather than for children?

I think it's because it doesn't offer hope. It's not a book in which a young hero knows enough to save himself, and the things that happen in it are very dark, and I'm not sure that I want to hand them to a kid, because I suspect what I want to hand mostly to kids is a certain amount of reassurance and a reminder that the world can be cool and all that kind of thing. So, I think that's part of it. I think that's significantly more part of it than the body horror in there with the worm or the sex or the darkness. I think there is some hopelessness in there, or at least there is a lack of hope.

Is there anything you haven't done yet that you know you'd like to do?

I really want to do a musical. I'd really like to be involved, day in, day out, with putting a good stage play together. Just haven't done it yet and really ought to.

You announced recently that you're taking a hiatus from social media. Why?

Mostly I think to get my attention span back. I find it harder and harder now to do things without wondering what's happening on Twitter and thinking maybe I should check my Twitter feed, or wanting to check my e-mail, or going "that's a really cool thing, I should stick that up on Tumblr," or feeling guilty that I'm not blogging. And I just like the idea of going, "Okay, I'll take a holiday, I will go cold turkey, I will take a rest." And I would like to be bored more. I don't think I get bored enough these days and I think boredom is a brilliant, brilliant way of coming up with ideas and, probably, I'm very, very likely to give up my phone for six months. I mean, if I'm going offline, I may well do it absolutely, go and hide out in the Isle of Skye or something like that. Anything could happen.

At this point in your career, are you able to take Stephen King's advice (mentioned in your "Make Good Art" speech) and think to yourself, "This is really great" and just "enjoy it"?

At this point in your career, are you able to take Stephen King's advice (mentioned in your "Make Good Art" speech) and think to yourself, "This is really great" and just "enjoy it"?

Sometimes, yes, but mostly I see the holes and not the solid places that the holes are in. You know, I definitely came away from an earth-shattering, epoch-making, ridiculous signing tour of America, over a few weeks of which well over 20,000 people were made really happy, and the book went in at #1 on the New York Times list, displacing that nice Mr. Brown, and all of that kind of stuff. And mostly all I was doing was just worrying about whether I'd get to the next signing stop on time and whether everything was going to keep working if it had worked, or whether it would be better the next time, if it hadn't. So, no, I do need to absolutely learn that lesson and learn it harder and learn it better. --Jennifer M. Brown

I think I should try and pay more attention to my creative process because I'm genuinely not sure at which point I decided I was going to write a riposte to The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and it would be called Fortunately, the Milk and it would be about dads. But I do think that the years of looking at The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and going, "this is not--and it's not even not positive--it's not a good thing for parents," and "I should do something which at least shows the other side of the coin." I suspect that sitting in my head for many years was the starting point.

I think I should try and pay more attention to my creative process because I'm genuinely not sure at which point I decided I was going to write a riposte to The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and it would be called Fortunately, the Milk and it would be about dads. But I do think that the years of looking at The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish and going, "this is not--and it's not even not positive--it's not a good thing for parents," and "I should do something which at least shows the other side of the coin." I suspect that sitting in my head for many years was the starting point. In The Graveyard Book, Bod finds a safe haven with the dead in the nearby cemetery; the nameless boy in The Ocean at the End of the Lane finds refuge with the Hempstocks, and the father in Fortunately, the Milk is aided by a stegosaurus and uses time travel to give his pursuers the slip. Do you think people often find refuge in places other than their biological families?

In The Graveyard Book, Bod finds a safe haven with the dead in the nearby cemetery; the nameless boy in The Ocean at the End of the Lane finds refuge with the Hempstocks, and the father in Fortunately, the Milk is aided by a stegosaurus and uses time travel to give his pursuers the slip. Do you think people often find refuge in places other than their biological families? You also play with the idea of parallel worlds in both serious and whimsical ways--two milk containers from different time periods for the father in Fortunately, the Milk; in Coraline, there's the mirror button-eye family and the real family; in Ocean, there's the ancient world that the boy narrator is privy to, and the real world that only his family sees. What attracts you to this interplay between seen and unseen worlds?

You also play with the idea of parallel worlds in both serious and whimsical ways--two milk containers from different time periods for the father in Fortunately, the Milk; in Coraline, there's the mirror button-eye family and the real family; in Ocean, there's the ancient world that the boy narrator is privy to, and the real world that only his family sees. What attracts you to this interplay between seen and unseen worlds? Let's pause here and reflect upon the fathers of your two recent books. In both Ocean and Fortunately, the Milk, the father is controlled by others. In Ocean, it's the otherworldly Ursula Monkton. In Fortunately, the father is at the whim of aliens, pirates, wumpires and Professor Steg. Why is that such a strong theme at this time?

Let's pause here and reflect upon the fathers of your two recent books. In both Ocean and Fortunately, the Milk, the father is controlled by others. In Ocean, it's the otherworldly Ursula Monkton. In Fortunately, the father is at the whim of aliens, pirates, wumpires and Professor Steg. Why is that such a strong theme at this time? In Ocean, you never name the boy-man narrator. Yet the importance of naming is essential to the plot. Why didn't you give him a name? Is he Everyman? (In the same way that Bod is Nobody?) The children and their parents get no names in Fortunately, the Milk, either. Coincidence?

In Ocean, you never name the boy-man narrator. Yet the importance of naming is essential to the plot. Why didn't you give him a name? Is he Everyman? (In the same way that Bod is Nobody?) The children and their parents get no names in Fortunately, the Milk, either. Coincidence? What makes Ocean a book for adults, rather than for children?

What makes Ocean a book for adults, rather than for children?