|

|

| Oliver Jeffers (l.) and Sam Winston | |

Oliver Jeffers is the author-illustrator of many books for children, including the award-winning Once Upon an Alphabet and Lost and Found. He is also the illustrator of The Day the Crayons Quit and its companion The Day the Crayons Came Home, both written by Drew Daywalt. Raised in Ireland, he now lives in Brooklyn.

Sam Winston is a fine artist whose work has been featured in many special collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, the Tate Galleries in London, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A Child of Books is his first picture book. He works and lives in London.

Winston and Jeffers collaborated on the innovative picture book A Child of Books (Candlewick, September 6, 2016), an homage to reading and imagination. Much of the book's visual landscape, from mountains to caves, is carved from blocks of type, painstakingly typeset story fragments hand-selected from a whole library of classic literature. Shelf Awareness spoke with them at the James Hotel in Chicago.

Congratulations on A Child of Books! I hear it took five to six years to finish.

Winston: It did!

How so?

Jeffers: Because we're both very bad at scheduling. No, we're very good at scheduling.

Winston: We're very good at overscheduling.

Jeffers: That's true. Because so much of the book had to happen when we were both in the same room, and Sam lives in London and I live in New York.

Winston: So our rooms are very far apart. But we did find a couple of good rooms in Georgia.

Jeffers: We removed ourselves from all the noise and distraction and went to rural Georgia and we were there for nearly two weeks.

How did that go?

Winston: It was a discipline not to just collapse it into deciding, right, okay... I'm pictures, you're words. Okay... it's this many pages. We were mates, but we were also very trusting, so one day Oliver's got a direction he wants to take out there, and one day I want to do this. We kept it as open as possible.

So each of you is both the author and the illustrator.

Winston: Yes. We like to confuse people.

Jeffers: Has that ever been done before, where two people are the author and two people are the illustrator?

I've never seen it. We could ask our readers. So, you two decided you wanted to work together first, and the plan came second?

Jeffers: A little bit of that, yeah. We were introduced by mutual friends and we liked the cut of each other's jib.

Winston: We did. We do.

So, what is, who is, "a child of books"?

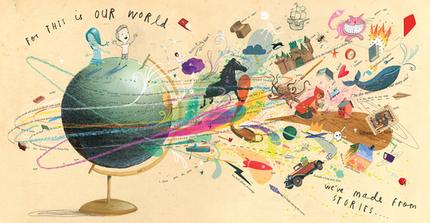

Jeffers: A child of books is this abstract idea of the life that lives within literature. This little girl personifies, or is the guide through all these classic stories. It's that on a more literal level, but it's really that she represents the joy of reading and imagination.

Winston: I think initially we just had the phrase "a child of books." We didn't know gender, we didn't know size or anything like that. And there's something really nice about the purity of this character being whatever you think it is. If someone says "a child of books," something comes to mind--childhood, reading, something magical, otherworldly. It's about that space where you get lost in a story for the first time.

Jeffers: I think that it's a very important moment where a kid first has that experience of actually watching the story happen inside their head. And then there's the joy of bringing that with you as you develop and grow.

|

|

How would you define your audience for this book?

Winston: The basic story is: There's a girl. She meets a boy. They go on an adventure. And then he leaves, quite happy that he's had an adventure. So that's a very young story. As older readers engage with the text and the images, it creates a really interesting dynamic between parent and child: "Mummy! What's Peter Pan?" "Well, Peter Pan's actually a story about..." And "Oh, yeah, Doctor Dolittle!" That gives parents a platform to share their childhoods and their literature... the book does a lot of talking... as we have been doing here.

Tell us about the boy character.

Winston: The girl introduces the world of stories to the boy character, who goes from a space where there's something about learning that is difficult or daunting. At some point you see the boy go from fear and challenge to "Wow, this is amazing!" Then suddenly, it's an acquired skill set, whether that's reading or imagination or creativity. A gift, full of potential. The child of books is like a muse for him, really.

Jeffers: Both of us share this belief that storytelling is one of the most important parts of a person's identity. You're no more than the stories that you tell and that are told about you. We quote Muriel Rukeyser in the book, who writes, "The universe is made of stories, not of atoms." And there's also this idea that true immortality is whenever somebody's story is remembered and told.

Winston: The other thing about storytelling is that we're in a really interesting time where we read across platforms, so there's a fluidity to language and information which is quite exciting, but also quite a challenge. But rather than get into a polemic of saying "Books are great" and "Digital is bad" or "Digital is fluid and brilliant" and "Books are old and old-fashioned," we thought, what are the amazing things that can be done in both mediums? The story of the child of books is our story, but we imply the vast amount of other stories, so we're looking at landscapes that are made out of all these other stories.

Jeffers: Which leads to the Alice in Wonderland bit in our book where she quite literally takes the other kid through a hole into this other world. There's the idea of getting in between the words.

|

|

The books you two chose to include are very old--and all classics.

Jeffers: Where to draw the line at a classic? There almost had to be a line drawn as to what constitutes a classic, so we kind of thought that because of the technology aspect of doing this, there's a nice Old World quality to it, too.

Winston: There's a practical element as well, using things that were outside of copyright, public domain stuff.

Were you big readers as children?

Winston and Jeffers: Yes. Mm hm.

Jeffers: Actually, I wasn't a big reader until I was a teenager. It was one of those things where, because I was told to read books I had no interest in it.

Winston: Yeah, and I was dyslexic, so I had a hell of a time learning how to read. So my first language was visual literacy.

Jeffers: I've heard a lot of designers are dyslexic because they see the words and letters as shapes rather than as words.

Winston: Which means that designers are famous for bad copy. And they can't spot spelling mistakes. But they make it look good. Storytelling and narrative didn't come easily for me, so I had to work out how people read. And that led to seeing language as an image, but also seeing text as texture.

So this is something of a revenge fantasy.

Winston: My whole career is basically a revenge fantasy.

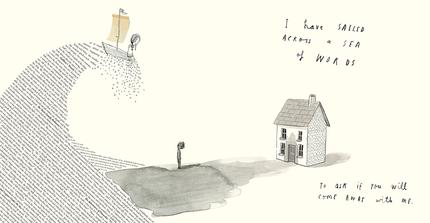

Right now we're looking at a sea of type from classic books on this spread... and it wasn't scanned.

Winston: No, that was typeset. Even five years ago I don't think there would be many Macs that would be able to handle the way the composition on the sea spread is made. That's like, I don't know, 800 or 900 individual text boxes, and each one was individually rotated. Just for that one spread.

Hence, five to six years of production?

Jeffers: Actually a lot of our time was figuring out how to print it because the black ink of the drawing is lithographically printed, so it's a different process than the way a novel would be printed. So trying to get those two different forms of technology to align perfectly required an awful lot of back and forth.

Winston: And we were very lucky that Walker and especially Deirdre who was our editor--and Candlewick--supported our project from the outset. They got it... and in a culture where "the quickest way is the best way," too. This project is the opposite of efficient. A true labor of love.

Tell us about the book's ending, when the boy walks away from the girl with her red book under his arm.

Winston: Every child has the possibility to dream, to imagine. Fundamentally we did the book because if we can get just one kid going away thinking "Wow! I feel like doing some drawings or I feel like writing!" Then... job done. So it ends with the boy walking away. I think it's really nice to start in the early 1800s, then have two people very much of the 2016s make something, and then maybe have a readership that becomes the authors of 2030 or 2045. Maybe they will do something old but new, because that's what this book is, old but new. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA book editor, Shelf Awareness