|

| (photo: Melissa Young) |

T.J. Newman was a flight attendant for Virgin America and Alaska Airline for a decade before turning to fiction. Now a full-time author, she made headlines when she garnered a significant deal for her first two books and the first novel, the in-air thriller Falling (Avid Reader Press), landed a $1.5 million film deal. Looking back on a whirlwind few months, Newman recalls the many red-eyes that led her to this moment.

You were a flight attendant for a decade. What took you down that career path, and how did it lead to your writing career now?

My mom and my sister were both flight attendants, so joining the "family business," as we call it, just made sense for me. But it was definitely a winding road to get there--and here. I studied musical theater in college and then moved to New York to pursue it as a career. Which was... well, I'll just put it frankly: failure. Nothing but rejection and failure. So I eventually left, moved back home to Arizona, moved back in with my parents and started trying to figure out what to do next with my life. That's when I got a job as a bookseller at Changing Hands Bookstore, which, as a life-long reader and writer, I loved. But when the opportunity to fly presented itself, I knew I couldn't pass it up so I left the store to go to training.

Throughout all of that I was writing stories. I didn't tell anyone I was. I didn't think I was smart enough or good enough to be a real writer. Plus, I was fresh off my mortifying bout of failure in New York, so I figured I'd already used up my personal quota for public creative risks.

But when I eventually had the idea for Falling, it was the first time my need to know what happened to the characters was stronger than my embarrassment and fear of failure. So I started working and I just didn't stop. I refused to let myself stop. I told myself I was going to finish it, and then I would make it better, and then I was going to get it published.

I'm curious where the first flash of an idea for Falling came from.

I was working a red-eye to New York and I was standing at the front of the cabin looking out at the passengers. It was dark. They were asleep. And for the first time a thought occurred to me--their lives, our lives, were in the pilot's hands. So with that much power and responsibility, how vulnerable does that make a commercial pilot? And I just couldn't shake the thought. So a few days later, I was on a different trip, with a different set of pilots, and one day I threw out to the captain: "What would you do if your family was kidnapped and you were told that if you didn't crash the plane, they would be killed? What would you do?" And the look on his face terrified me. He didn't have an answer. And I knew I had the makings of my first book.

You wrote much of this book while you were actually in the air. Did it make the terror feel more visceral, actually imagining the plane you were currently on crashing?

Pilots and flight attendants spend a lot of time analyzing aviation accidents and incidents. We study what went wrong, why it went wrong, what the crew did right and what the crew did wrong. We're constantly mentally putting ourselves in emergency scenarios and asking ourselves what we would do, how would we handle it. It's how we learn. It's how we're trained to think. So imagining this particular scenario on the plane didn't feel all that odd, to be honest. It just felt like a heightened and more intense scenario than what I would normally be thinking about.

What was your writing and editing process while you were working full-time? Did you write most of the story in a jump seat?

I usually worked as a "Lead" or "A" flight attendant, meaning I worked in first class--which meant I had the forward galley to myself. And because I worked a lot of red-eyes (flights with a light workload since everyone is asleep), I'd have a lot of time to do my own thing. So I'd stand in my galley and write by hand--calmly turning over the paper or slipping it into the drawer beneath the coffee pot in a very "nothing to see here, folks" kind of way whenever a passenger or another flight attendant appeared. Then, on my layovers in my hotel room or at a coffee shop, I'd transfer my work to my iPad.

This has been a wild experience for you, with the seven-figure book deal quickly followed by the seven-figure film rights. How have you been keeping your head straight during this time period?

I'm so grateful and so humbled about everything that's happened. It truly has been a whirlwind experience and I don't know what I'd do without my incredible family who have kept me grounded through all of it. Plus, I've got another book due so I'm working on getting my pages in.

Other than a scary good ride, what do you hope readers will get from this story?

I'd love for readers to walk away with a broader understanding and deeper respect for what flight crews do. Especially flight attendants. I think there's a common misconception that FAs are on board for service. And that's just not true. I assure you, if it was, the airlines would have stopped paying us and replaced us with vending machines a long time ago. Flight attendants are there for your safety and security. Service is just something we gladly provide. So I'd be thrilled if a reader remembers that the next time they feel the impulse to roll their eyes at the flight attendant who asks them to bring their seat back up or to stow their bag. They're not trying to inconvenience you. They're trying to protect you. --Lauren Puckett

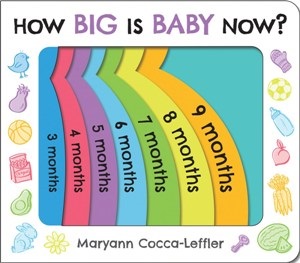

Maryann Cocca-Leffler uses die-cuts and page turns to excellent effect in her brightly colored book How Big Is Baby Now? (Sourcebooks Explore, $10.99) The cover displays seven stages of a pregnant belly (three months to nine months), the die-cut taking up the negative space in front of the belly. That space gets smaller as the baby gets bigger, growing from the size of an egg to the size of a football to, eventually, the size of a pumpkin (or toaster). Children ages 4-6 will surely be drawn into the tactile experience of this book that appears to have more open space than paper.

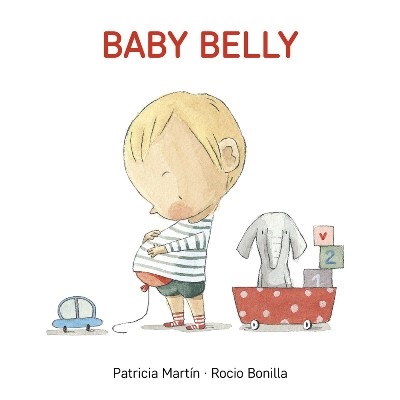

Maryann Cocca-Leffler uses die-cuts and page turns to excellent effect in her brightly colored book How Big Is Baby Now? (Sourcebooks Explore, $10.99) The cover displays seven stages of a pregnant belly (three months to nine months), the die-cut taking up the negative space in front of the belly. That space gets smaller as the baby gets bigger, growing from the size of an egg to the size of a football to, eventually, the size of a pumpkin (or toaster). Children ages 4-6 will surely be drawn into the tactile experience of this book that appears to have more open space than paper. In the wordless Baby Belly by Patricia Martin, illustrated by Rocio Bonilla (Magination Press, $7.99), a toddler wonders about their parent's growing belly. What could be in there? When the toaster-sized belly begins moving, the child begins to understand. Martin uses a soft natural palette, bringing a sense of realism to this sweet story. This gentle board book is excellent to share with pre-readers and as preparation for a new sibling.

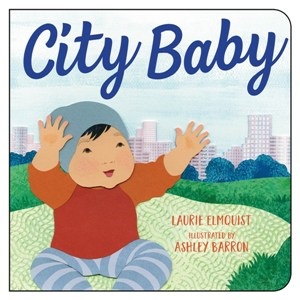

In the wordless Baby Belly by Patricia Martin, illustrated by Rocio Bonilla (Magination Press, $7.99), a toddler wonders about their parent's growing belly. What could be in there? When the toaster-sized belly begins moving, the child begins to understand. Martin uses a soft natural palette, bringing a sense of realism to this sweet story. This gentle board book is excellent to share with pre-readers and as preparation for a new sibling. And then the baby arrives! City Baby by Laurie Elmquist (Orca, $10.95) gives the very young a dazzlingly illustrated view of the life of a baby. While the title suggests it's only for urban kids, the book includes activities in which every baby can take part: blowing bubbles, playing trains and zooming planes. Simple text and gorgeous mixed-media paper collage art by Ashley Barron make this an utterly entertaining read-aloud.

And then the baby arrives! City Baby by Laurie Elmquist (Orca, $10.95) gives the very young a dazzlingly illustrated view of the life of a baby. While the title suggests it's only for urban kids, the book includes activities in which every baby can take part: blowing bubbles, playing trains and zooming planes. Simple text and gorgeous mixed-media paper collage art by Ashley Barron make this an utterly entertaining read-aloud.

The novel Push by Sapphire, published in 1996, follows Claireece Precious Jones, an obese, illiterate teenager living with her abusive mother in Harlem. Precious is pregnant a second time after being raped by her father--her first child, conceived the same way, has Down syndrome and lives with her grandmother. When her pregnancy is discovered, Precious is transferred to an alternative school for young women who cannot read or write well enough to complete high school. Her new teacher, Ms. Rain, in addition to instruction on basic vocabulary and grammar, ignites a passion for literature and poetry through the work of Black writers like Audre Lorde, Alice Walker and Langston Hughes. After giving birth to her son, Abdul, Precious becomes homeless, ends up in a halfway house and discovers she has contracted HIV from her father. Push, told from Precious's perspective, begins with many phonetically spelled words and simple sentences. As her education advances, so too does the prose, eventually including similes and images inspired by her love of poetry.

The novel Push by Sapphire, published in 1996, follows Claireece Precious Jones, an obese, illiterate teenager living with her abusive mother in Harlem. Precious is pregnant a second time after being raped by her father--her first child, conceived the same way, has Down syndrome and lives with her grandmother. When her pregnancy is discovered, Precious is transferred to an alternative school for young women who cannot read or write well enough to complete high school. Her new teacher, Ms. Rain, in addition to instruction on basic vocabulary and grammar, ignites a passion for literature and poetry through the work of Black writers like Audre Lorde, Alice Walker and Langston Hughes. After giving birth to her son, Abdul, Precious becomes homeless, ends up in a halfway house and discovers she has contracted HIV from her father. Push, told from Precious's perspective, begins with many phonetically spelled words and simple sentences. As her education advances, so too does the prose, eventually including similes and images inspired by her love of poetry.