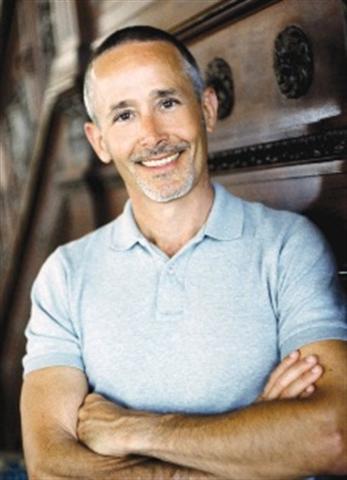

Joshua Henkin is the author of Swimming Across the Hudson, a Los Angeles Times Notable Book, and Matrimony, a New York Times Notable Book; his stories have been published widely. He lives in Brooklyn and directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The impulse to write--and read avidly--has always been with him, and after giving up a young man's dream of being a basketball player, he turned to writing. In his new book, The World Without You (reviewed below), the Frankel family gathers at their home in the Berkshires for a memorial one year after Leo, a journalist, was killed in Iraq. In conversation, Henkin is an engaging raconteur; serious but not stodgy; voluble, easy to talk to, engaged and responsive. He talks much like he writes--you can't stop listening and you can't stop reading.

Joshua Henkin is the author of Swimming Across the Hudson, a Los Angeles Times Notable Book, and Matrimony, a New York Times Notable Book; his stories have been published widely. He lives in Brooklyn and directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The impulse to write--and read avidly--has always been with him, and after giving up a young man's dream of being a basketball player, he turned to writing. In his new book, The World Without You (reviewed below), the Frankel family gathers at their home in the Berkshires for a memorial one year after Leo, a journalist, was killed in Iraq. In conversation, Henkin is an engaging raconteur; serious but not stodgy; voluble, easy to talk to, engaged and responsive. He talks much like he writes--you can't stop listening and you can't stop reading.

How do you approach beginning a novel?

I think about characters more than about subjects or events. Kids are the most natural storytellers and their stories are about people or animals, not necessarily about events. Stories all start and end with characters. When starting a novel, you can't see the forest for the trees or even if it is a novel at all. The challenge for the novelist is in ceding control and letting it happen. It usually takes about two years for it to take shape--in the case of Matrimony, it took nine years. Just write a page a day, no matter what, and then look at it. If the novelist is certain at the beginning of where the story is going, that's not a good sign. I know very, very little when I first sit down to write. The subconscious takes over and eventually I have a first draft. Characters evolve and develop and their stories are created as I go. Signposts are fine, but you can't get attached to them. The novel has to be allowed to breathe. Then, there are as many revisions as it takes.

You've written many short stories, as well as three novels. Is there a difference in the two disciplines?

The approach to a short story is very different. With a short story, you revise as you go. I was trained as a story writer and I am still very interested in the form. For the short story writer, it is in distilling the work so you find that single moment when it all happens; you sometimes get a sense of the whole at the beginning.

Your novels are preoccupied with family or marriage. Why this concentration?

We all grow up in some version of a family, however scattered or bonded it might be, so there is some relevance. My own family was not ordinary. My grandfather was an Orthodox rabbi who lived on the Lower East Side of New York all his life and spoke not a word of English. My father was raised Orthodox; my mother was a secular Jew, not observant. We were idiosyncratic practitioners. As a novelist, I am fascinated with time and connected to family history through Judaism.

The characters in The World Without You seem bent on hurting each other. Even though they seldom gather, there is no attempt to "make nice."

This is a very political family which sets up even more potential for conflict. No two people are exactly alike and in this family there are significant differences and real or imagined grudges. Relations are harmonious in some families, but there are no generalizations about that. Fiction is anti-generalization, always about the particular. Setting the story on the Fourth of July weekend was not a conscious nod to "independence," but it is ironic that while the rest of the country is celebrating independence, all of these people who have strong feelings about the war are people of privilege who have been touched by this war in a way they could not have possibly imagined.

Daughter Noelle is the most outspoken, the most hurtful, probably because she has never felt accepted. She also has chosen an extremely rigorous and demanding religious life. Is she making up for a rather louche young life?

Yes, she needs the structure and discipline that Orthodox Judaism provides.

Her husband, Amram, is a bit of a wild card--setting up everyone to fail at the game of "Celebrity" to make himself feel important and then leaving the house to return just in time for the memorial.

Her husband, Amram, is a bit of a wild card--setting up everyone to fail at the game of "Celebrity" to make himself feel important and then leaving the house to return just in time for the memorial.

Amram has always wanted to be a hero. He believes that he can transform himself--lose weight, gain weight, try to gain the spotlight. He is fine in Israel, where he and Noelle live, but marginalizes himself in the Frankel family. In trying to save face, he loses face. Going to pick up Grandma is another attempt to be a hero. The family memorial is incomplete without Grandma, who is the puppeteer with the money. She pulls the strings, and in agreeing to appear with Amram she completes the family picture, as in a Greek tragedy when everyone is on stage when it ends.

The father, David, is almost a bystander, burdened by his own way of grieving--so different from that of his wife.

He has a different relationship with each child, too--a very good one with Lily, he's good with Clarissa and it is always difficult with Noelle. He does discuss with [Leo's wife] Thisbe what will become of their relationship with [her son] Calder as she moves on with her life, another painful passage for him as he is all they have left of their son. He is a silent observer with his own integrity in a story largely centered on the women in it.

What's on the desk now?

I've been working on short stories for a while. I thought that I had six or seven, but one is almost the length of a novella. I have an idea for a novel, but it isn't clear yet. I write every day. --Valerie Ryan

Joshua Henkin: The Impulse to Write

Joshua Henkin

Joshua Henkin Her husband, Amram, is a bit of a wild card--setting up everyone to fail at the game of "Celebrity" to make himself feel important and then leaving the house to return just in time for the memorial.

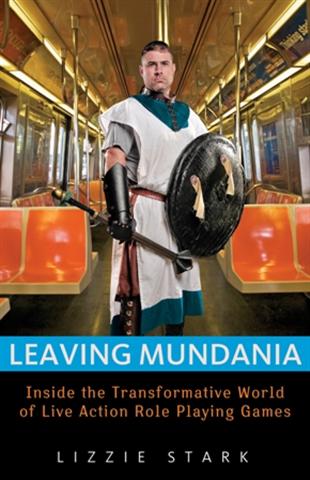

Her husband, Amram, is a bit of a wild card--setting up everyone to fail at the game of "Celebrity" to make himself feel important and then leaving the house to return just in time for the memorial. Lizzie Stark

Lizzie Stark Book you've faked reading:

Book you've faked reading: I grew up in a long-ago era (the 1960s) when there was very limited contact between readers and writers. Few authors made public appearances, and few readers had any clear idea of where to address a letter to a favorite writer. I thought of the author-reader relationship as strictly one-way. Like a river, storytelling ran in a single direction, from those who wrote to those who read.

I grew up in a long-ago era (the 1960s) when there was very limited contact between readers and writers. Few authors made public appearances, and few readers had any clear idea of where to address a letter to a favorite writer. I thought of the author-reader relationship as strictly one-way. Like a river, storytelling ran in a single direction, from those who wrote to those who read.