|

| photo: L. D'Alessandro |

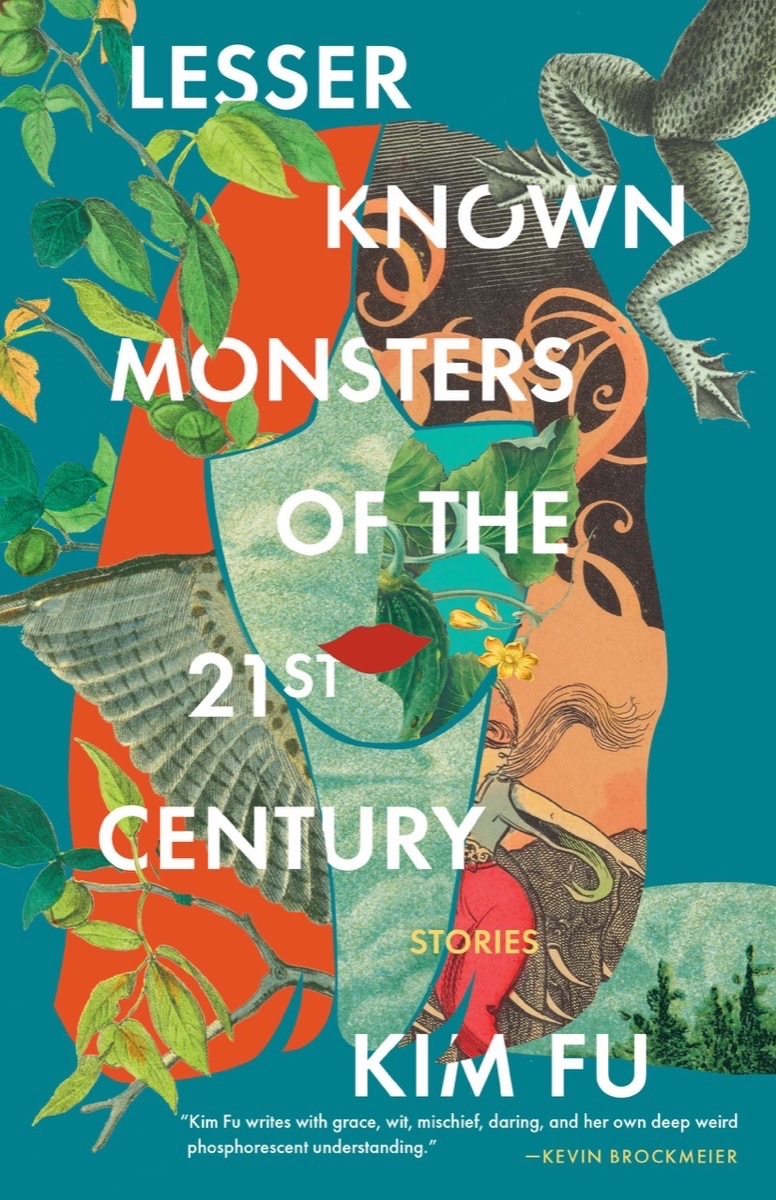

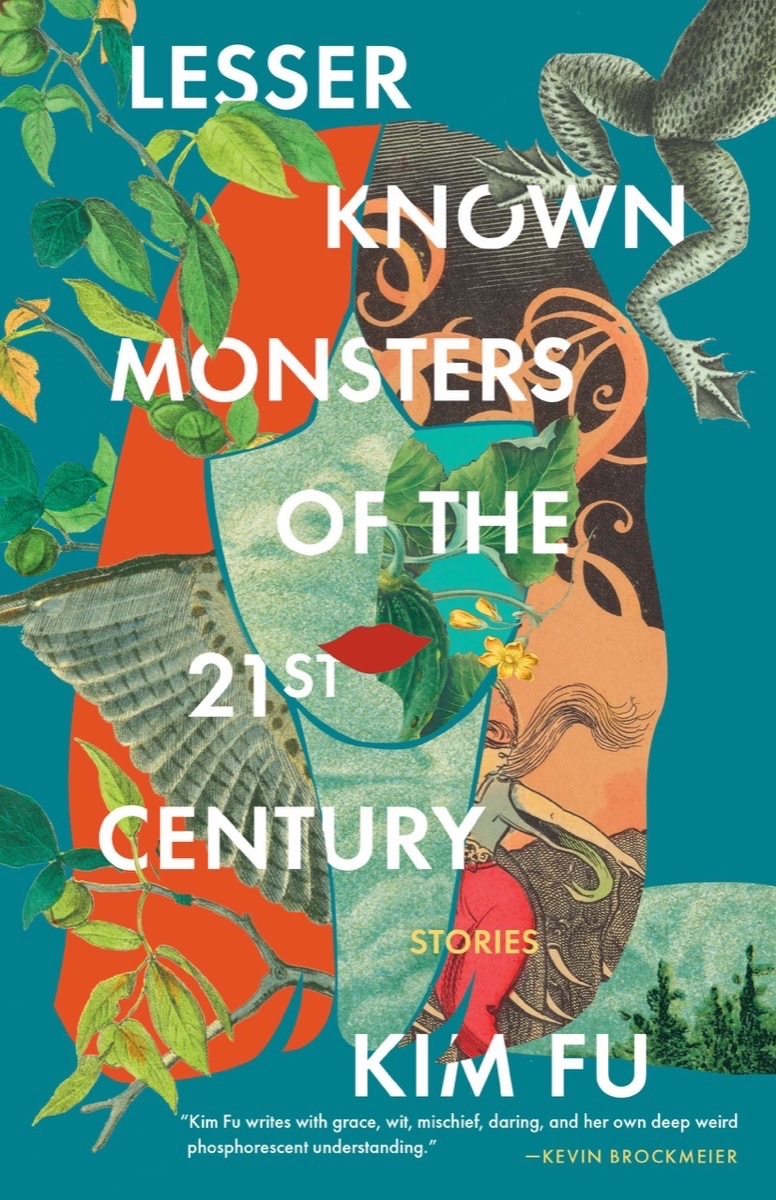

Kim Fuis a writer of fiction and poetry from Vancouver, B.C., now living in Seattle, Wash. Her novel For Today I Am a Boy won the Edmund White award for Debut Fiction. Her second novel, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore, was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award. Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century, her first collection of short stories (reviewed below), is available now from Tin House.

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century follows your two novels and a book of poems. What challenges, or opportunities, does short fiction present compared to novels and poetry?

As a reader, I love a novel's slow accumulation of meaning: scenes layering on top of each other, tangents that obliquely connect in the end, long journeys with varied pleasures along the way. But when I read a short story, I tend to want something more tightly structured, turning upon one key moment or idea. I want stories to be irreducible and sharply satisfying, like the punchline of a joke. You want to construct a universe that's just as complete and immersive as that of a novel, to make your characters' lives feel just as full and rich, while using only a fraction of the textual space. So much has to exist off the page.

It's an entirely different challenge to try to find the handful of details that will imply a whole world to the reader. Writing a novel feels like building a house while living on site; writing a short story feels like building a tiny, intricate machine, like the inner workings of a watch: minuscule gears and springs and gemstones that have to fit just so. (Writing a poem is something else entirely--like gathering flowers from a field, arranging a bouquet, setting the bouquet on fire, and then asking other people to admire the ashes. Incredibly, sometimes they do.)

In several of these stories--especially "Liddy, First to Fly" and "The Doll"--you write evocatively from the perspective of young characters in the transition between childhood and adolescence. What is it about that stage of life that makes for such fertile ground for fiction?

I think most of us remember those years as almost unbearably intense. Everything is new, everything is changing. Children that age plaster over gaps in their understanding with speculation and imagination, inventing the world around them as they try to make sense of it. They form complex, capricious social hierarchies just outside the awareness of adults; they make plans and play games that hover between the pretend play of their younger selves and the real dangers of the material world. It's an endlessly fascinating age. And puberty already unfolds like a horror movie: your body and the bodies of your peers transforming suddenly, grotesquely, in ways you don't necessarily understand, that some of you long for and some of you fear.

Many of these stories feature eerie, unshakable images--the hooded figure in "Sandman," for example, or the swarm of beetles in "June Bugs." Do your stories spring from an image, or do you find the image in the course of your process?

I can't start writing until I have an image. If an idea comes to me in another form--a scenario, a character, a what-if, a voice in dialogue--I can't put any words down on the page until I connect it to some sensory detail. In writing "Scissors," for example, I couldn't find my way into the story until I landed on the smell of dust burning on the stage lights. "Sandman" is a story about insomnia, and I've had trouble sleeping since I was a small child, with no shortage of experiences to draw on, but there was no story until I saw the figure in the hooded cloak, sand pouring from the darkness where his face should be. Even "Pre-Simulation Consultation XF007867," a story told entirely in dialogue, needed the image of the simulated experience one of the characters is seeking: a woman and her dead mother walking through a botanical garden. In early drafts, I often build from images and never really know where I'm going. I only ever outline retroactively, between later drafts, where the real work happens. I can't make an outline first and follow it, even though that seems like a much more efficient and enviable way to write (and one I know works well for lots of other, better writers).

Two of my favorite stories in the book, "Twenty Hours" and "Bridezilla," involve relationships marked by very grounded, recognizable anxieties. They also involve 3D-printed human bodies and a symbiotic Lovecraftian sea monster, respectively. What do you enjoy about infusing mundane human affairs with the fantastical like this?

Two of my favorite stories in the book, "Twenty Hours" and "Bridezilla," involve relationships marked by very grounded, recognizable anxieties. They also involve 3D-printed human bodies and a symbiotic Lovecraftian sea monster, respectively. What do you enjoy about infusing mundane human affairs with the fantastical like this?

I like how a fantastical element can sharpen a muddier, more nebulous emotion--literalize it, manifest it as something you can see, a monster you can look in the eye. In "Twenty Hours," the body printer changes indistinct, low-level ennui and boredom between a married couple, what they gain and what they give up by being together, into a black-and-white question of life and death. In "Bridezilla," I hope the main character's cocktail of modern anxieties--around femininity, white womanhood, performativity, climate change--are given new perspective by the lurching sea monster on the horizon.

I also think it's an opportunity to make emotions as big as they feel, in a way that realistically describing the situation might not. That's also something I love about poetry. Maybe love and grief are best described as a magical machine or a haunting or a bug infestation.

These stories frequently veer into the territories of science fiction and horror, which made me curious about what influences found their way into the book. Were they different from your previous influences?

I try to read broadly, and science fiction and horror have always been a part of that, and speculative and fantastical elements have been a part of the "literary fiction" landscape for as long as I've been reading. In the years I was writing and editing this book, I did particularly like Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich. I discovered Ellen Klages because of the Levar Burton Reads podcast, which focuses on science fiction and fantasy. Ted Chiang, Karen Russell and George Saunders are masters, of course.

Before the pandemic, one of my favorite things in the world was going to the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library for their Thrilling Tales "story time for grown-ups," where librarian David Wright would do dramatic readings of short stories old enough to be in the public domain, mostly early science fiction, ghost stories and pulpy fun. It lives on as a podcast, but I miss the in-person version dearly.

When assembling a book of stories, how do you know when you're done?

There came a point where I felt like these stories were cumulatively saying something, that they were thematically threaded together in a way I could no longer expand or tease apart, and I wanted to move on, maybe to new ideas that required new forms. I lean on my agent, editors and friends to guide me, but I do always hit a point where I feel finished with a book, where it feels as complete and untouchable--and as imperfect and personal--as a dream. You wake up and can't go back. --Theo Henderson, bookseller at Ravenna Third Place Books in Seattle, Wash.

Kim Fu: Monsters You Can Look in the Eye

Rachel Lynn Solomon managed to pack a full list of romance tropes into her hit novel, The Ex Talk; in her newest, Weather Girl (both Berkley, $16), she plays with the second-chances trope, as a meteorologist and a sports reporter at a local broadcast station hatch an unlikely plan to get their divorced bosses back together. Jasmine Guillory (The Wedding Party; Party of Two) plays with the "fake dating" trope in While We Were Dating (all Berkley, $16); movie star Anna Gardiner and colleague Ben Stephens really are sleeping together, after all, even though the relationship they agree to put on for the paparazzi is just for show--at least, until their feelings become all too real.

Rachel Lynn Solomon managed to pack a full list of romance tropes into her hit novel, The Ex Talk; in her newest, Weather Girl (both Berkley, $16), she plays with the second-chances trope, as a meteorologist and a sports reporter at a local broadcast station hatch an unlikely plan to get their divorced bosses back together. Jasmine Guillory (The Wedding Party; Party of Two) plays with the "fake dating" trope in While We Were Dating (all Berkley, $16); movie star Anna Gardiner and colleague Ben Stephens really are sleeping together, after all, even though the relationship they agree to put on for the paparazzi is just for show--at least, until their feelings become all too real. In Love and Other Disasters (Forever, $15.99), the first openly nonbinary contestant on a competitive cooking show develops unexpected (and inconvenient) feelings for another contestant. Exploring topics of identity and sexuality with heart, Anita Kelly's debut is a must for any romance reader with an interest in Top Chef-style shows (or vice versa).

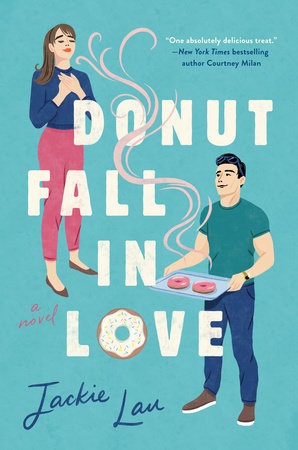

In Love and Other Disasters (Forever, $15.99), the first openly nonbinary contestant on a competitive cooking show develops unexpected (and inconvenient) feelings for another contestant. Exploring topics of identity and sexuality with heart, Anita Kelly's debut is a must for any romance reader with an interest in Top Chef-style shows (or vice versa). Donut Fall in Love by Jackie Lau (Berkley, $16) boasts a movie-star romance and a competitive cooking show, as hot-shot Ryan Kwok preps for his upcoming participation in a charity baking challenge by taking lessons in baking--and romance--from a local donut shop owner. The two hit it off as each navigates their respective grief over losing a parent, offering a heartwarming read for anyone who's ever thought about taking new chances in the wake of loss. --Kerry McHugh, freelance writer

Donut Fall in Love by Jackie Lau (Berkley, $16) boasts a movie-star romance and a competitive cooking show, as hot-shot Ryan Kwok preps for his upcoming participation in a charity baking challenge by taking lessons in baking--and romance--from a local donut shop owner. The two hit it off as each navigates their respective grief over losing a parent, offering a heartwarming read for anyone who's ever thought about taking new chances in the wake of loss. --Kerry McHugh, freelance writer

Two of my favorite stories in the book, "Twenty Hours" and "Bridezilla," involve relationships marked by very grounded, recognizable anxieties. They also involve 3D-printed human bodies and a symbiotic Lovecraftian sea monster, respectively. What do you enjoy about infusing mundane human affairs with the fantastical like this?

Two of my favorite stories in the book, "Twenty Hours" and "Bridezilla," involve relationships marked by very grounded, recognizable anxieties. They also involve 3D-printed human bodies and a symbiotic Lovecraftian sea monster, respectively. What do you enjoy about infusing mundane human affairs with the fantastical like this?