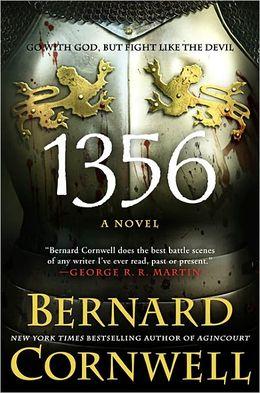

Bernard Cornwell has written more than 50 novels, mostly historical fiction, including the bestselling Sharpe series. His newest is 1356 (Harper, January 8, 2013). Cornwell's thorough knowledge of history is evident and lays the groundwork for the novel's setting, but it is his masterful storytelling talent that makes 1356 an engrossing, larger-than-life action adventure. Juggling both intricately developed characters and meticulously detailed plot, Cornwell drops the reader in the middle of 14th-century Europe as the French and English clash at the Battle of Poitiers.

Bernard Cornwell has written more than 50 novels, mostly historical fiction, including the bestselling Sharpe series. His newest is 1356 (Harper, January 8, 2013). Cornwell's thorough knowledge of history is evident and lays the groundwork for the novel's setting, but it is his masterful storytelling talent that makes 1356 an engrossing, larger-than-life action adventure. Juggling both intricately developed characters and meticulously detailed plot, Cornwell drops the reader in the middle of 14th-century Europe as the French and English clash at the Battle of Poitiers.

Dealing with history can be a volatile task. Sometimes the facts change depending on the perspective of the person relating the story. How do you handle these situations?

You run into that situation all the time! It's inevitable, especially dealing with military history, which I do. If you look at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris you'll see the battle of Fuentes d'Onoro incised as a French victory, a conclusion that the Duke of Wellington would have found astonishing, as he believed he had won that battle! There are hundreds of such examples, and all any storyteller can do is look at the evidence on both sides and make a decision. With Fuentes d'Onoro it's quite easy; the French made an attempt to relieve the siege of Almeida and failed, so we can disregard the claim that it was a "victory" when it palpably was not, but other cases are trickier. I wrote a book about the battle of Penobscot Bay during the American Revolution and it featured Paul Revere very prominently. Revere, of course, is a hero, but all the evidence (apart from his own diary) indicated that he was ineffective, possibly cowardly and unbelievably difficult for his own side to deal with. That's tricky because you're flying in the face of popular myth, but in the end I went with the contemporary evidence and am certain that was the right decision.

You have written books set in different time periods, some in the U.K., some in the U.S. What were some of the challenges you faced with 1356?

Probably the biggest challenge was simply to establish where the battle took place! Historians disagree, and I thought a visit to the battlefield would clear it up. It usually does. I've visited scores of battlefields, and whenever there's some mystery it's usually possible to work out from the lay of the land what happened, but Poitiers was impossible! Many of the most prominent landmarks have vanished over the centuries, and the terrain didn't offer an answer to the biggest question, whether the French approached from the north or the west (or anywhere in between), so in the end I made a decision based on a hunch rather than on the evidence.

Two major plot points in 1356 are the Battle of Poitiers and the search for la Malice, the sword Peter uses in the Garden of Gethsemane. In your historical note, you mention that you were attracted to the Battle of Poitiers because it seems to have been lost in history, despite its amazing outcome. How about la Malice; what made you choose to include this in Thomas Hookton's tale?

Two major plot points in 1356 are the Battle of Poitiers and the search for la Malice, the sword Peter uses in the Garden of Gethsemane. In your historical note, you mention that you were attracted to the Battle of Poitiers because it seems to have been lost in history, despite its amazing outcome. How about la Malice; what made you choose to include this in Thomas Hookton's tale?

It just seemed a good idea! I wanted Thomas to be involved with a relic, and there were many candidates, such as a thorn from the crown of thorns, or a sliver of the true cross, or a nail, or some bodily remnant of a saint, but all those things are familiar. Then one day I remembered Saint Peter's sword, mentioned in the Gospels, and somehow that has never gained the fame of other relics. It also seemed an appropriate object for a soldier to pursue. The Archdiocese of Poznan, in Poland, claims to have the sword (I named it la Malice), and indeed they do have a sword, but whether it's the real thing? Who can tell?

In an interview with George R.R. Martin, you brought up the possibility that your characters are a reflection of yourself. Do you think that's true about Thomas Hookton, and if so what parts of him are reflections of you?

I said that? I don't think any part of Thomas is a reflection of me! I wish! I suppose Sharpe has some of my less attractive traits (those are the ones most easily transferred to characters), but I can't think any of me is in Thomas.

Thomas is an English archer. Have you used a longbow similar to what Thomas would have used?

I have, and it was an extraordinary experience. A modern competition bow has a draw weight of 40 lbs., while an English war bow of the 14th century has a draw weight upwards of 120 lbs. That is massive! I tried, and could scarcely pull the cord back six or seven inches, and found the tension in the cord and stave to be frightening. There are still a few men (and women?) who can pull that weight and, like the longbowmen of old, do it 15 or more times a minute, but it takes extraordinary strength.

You are not the first author I've heard say they started writing in a particular genre because they loved to read it, but then after they began writing in the genre, it became much less enjoyable to read. What do you read these days?

I read history; vast amounts of history, I just avoid most historical novels! It's very hard to spend all day writing and then reading the same "stuff" at night, but it hasn't soured my taste for "real" history. And I read a lot of novels, but they tend to be contemporary. I make a few exceptions; I adore C.J. Sansom's novels about Matthew Shardlake, the Tudor lawyer, and Hilary Mantel is a goddess! I also like police procedurals, because I could never write one! I particularly like John Sandford's and Stuart McBride's novels.

Did your interest in the nonfiction come first, making Horatio Hornblower so fascinating or did your interest in Horatio Hornblower trigger the fascination in nonfiction?

Hornblower led the way! I became an addict when I was a teenager and, when there were no more Hornblower books to read (he wrote only 11), I went on to read the nonfiction history books about the Napoleonic era.

With the enormous selection of historical events to choose from, are there characteristics that typically grab your attention and encourage you to opt for one event over another? And do you choose something at the conclusion of each novel or do you have several novels planned in advance?

I wish I knew! I don't. It's a capricious process. I guess I write about things that attract my interest, but quite what it is, I don't know. I did want to write about the making of England, another story, like the Battle of Poitiers, that is lamentably unknown, so writing the Saxon adventures of Uhtred was a natural thing to do. I do have plans for the next couple of books, but I am superstitious and know that the books will fail if I tell those plans to anyone. So I don't!

You've also taken up acting on stage. Have your experiences as an actor influenced your writing?

I suspect it's the other way round! I think the quality that writing takes to the stage is years of "listening" to dialogue in my head. When writing dialogue, the words have to be shaped to convey mood and meaning to the reader, and I definitely hear the speaker's inflections as I write, and that experience makes it easier to deliver lines on stage.

And finally, what's next?

Right now I'm writing the next installment of Uhtred's story, which I hope to finish in the spring. I'm almost halfway through, he's behaving extremely badly, so all is well with the world. --Jen Forbus of Jen's Book Thoughts

Bernard Cornwell: Addicted to History

Obama's first debate performance was a disaster; first debates for incumbents usually are. But after the elation the campaign felt at Romney's "47%" debacle, "[Obamaland's] utter confidence in one of the best talkers in American political history" had been shaken. Not news now, but what Hastings digs into before, after and during this mini-crisis, is the good stuff. He's hard on the press for amping up the panic to make the news cycle interesting again.

Obama's first debate performance was a disaster; first debates for incumbents usually are. But after the elation the campaign felt at Romney's "47%" debacle, "[Obamaland's] utter confidence in one of the best talkers in American political history" had been shaken. Not news now, but what Hastings digs into before, after and during this mini-crisis, is the good stuff. He's hard on the press for amping up the panic to make the news cycle interesting again.

Bernard Cornwell

Bernard Cornwell Two major plot points in 1356 are the Battle of Poitiers and the search for la Malice, the sword Peter uses in the Garden of Gethsemane. In your historical note, you mention that you were attracted to the Battle of Poitiers because it seems to have been lost in history, despite its amazing outcome. How about la Malice; what made you choose to include this in Thomas Hookton's tale?

Two major plot points in 1356 are the Battle of Poitiers and the search for la Malice, the sword Peter uses in the Garden of Gethsemane. In your historical note, you mention that you were attracted to the Battle of Poitiers because it seems to have been lost in history, despite its amazing outcome. How about la Malice; what made you choose to include this in Thomas Hookton's tale?