|

| photo: Justin Lane |

Carlene Bauer is the author of the memoir Not That Kind of Girl, described as "soulful" by Walter Kirn in Elle and "approaching the greatness of Cantwell" in the New York Post. She has written for n +1, Slate, Salon and the New York Times and lives in Brooklyn, N.Y. Bauer's debut novel, Frances and Bernard, will be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on February 5, 2013.

Can you tell us a bit about the background of Frances and Bernard--how you decided to write an epistolary novel set in the literary scene of New York City in the 1950s and '60s?

About 10 years ago I read Paul Elie's The Life You Save May Be Your Own, which is a biography of four American Catholic writers, Flannery O'Connor being one of them. In the book Elie discusses how O'Connor and Robert Lowell met at Yaddo and became friends, and there is also some suggestion that perhaps O'Connor had a little bit of a crush on Lowell. This surprised me. I didn't know that they were friends, and O'Connor wasn't a writer who turned her love life into an ancillary art project. I wondered--what on earth would it have been like if they actually had some sort of affair? It was hard to imagine them being friends, let alone lovers, their temperaments being so different.

|

| photo: David McLane/NY Daily News |

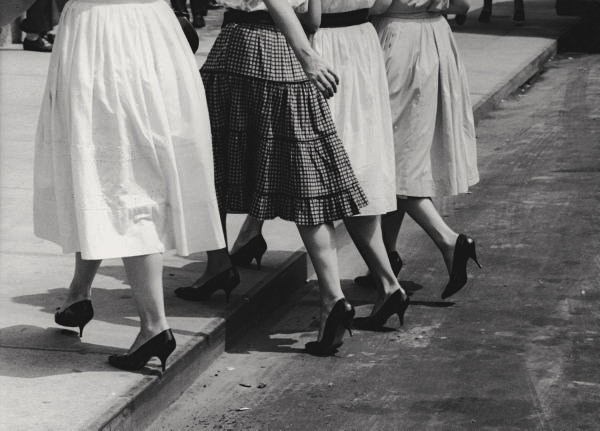

In the months before my first book was published, wanting to start another project, I tried to imagine what would happen if two characters inspired by Lowell and O'Connor, sharing those temperaments and some biographical details, did fall in love. It was a classic "What if?" impulse. Setting it in the literary scene of '50s and '60s New York was dictated somewhat by the facts, somewhat by my desire for verisimilitude and somewhat by inclination. That was the milieu known by Lowell and, to a lesser degree, O'Connor, and it seemed to me that the time and the place would make the characters' struggles with religion and love more believable. Setting the book in this period also allowed me to indulge my fantasy that I had a past life as a lady screenwriter of screwball comedies starring Rosalind Russell.

It became an epistolary novel when my third-person omniscient attempt at this story was not as alive as I wanted it to be. The correspondence between Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop had been published around the time I'd begun work on the novel, and watching those two navigate a lifelong friendship reminded me that letters could be a vehicle for drama between characters. You could pack scenes, memories, character assessments (or assassinations!)--whatever you needed--into letters. And you would create, hopefully, a powerful sense of intimacy between the reader and the characters, because you would have a more unfettered access to their consciousness.

Though the book is for the most part a tête-à-tête between Frances and Bernard, God is almost as much a presence in the novel--though not literally, of course. You wrote a memoir about the impact of religion in your life. Do you see this novel as a further exploration of this theme?

Yes. In a talk she gave on Southern fiction and the grotesque, Flannery O'Connor described her native region as "Christ-haunted." I'd like to borrow that phrase and say that I am God-haunted. I was raised evangelical and then very briefly converted to Catholicism before giving up belief at 29, but I think I'll always be asking questions about faith, and will always be interested in narratives about it, especially narratives about losing your religion. What is it like, life after God? What parts of faith are we reluctant to let go of? How can we create meaning when we don't have religion as a framework? Are we giving up too easily when we set God aside, as Frances suggests (and as I imagine some people have wanted to suggest to me)? I realize it is very American to be asking these questions in the first place, but I think there are more people living these quandaries than get written about in trend pieces on evangelicals--or in novels, as Paul Elie recently pointed out. It can be lonely, asking yourself these questions without the support of a community like a church, knowing, of course, that you forfeited that kind of community the first moment you found yourself thinking skeptically. But I think books can provide some solace for those in the midst of this kind of wrestling.

One aspect of an epistolary novel is that we only find out what the characters choose to reveal to one another in correspondence. How do you think this subjectivity serves the story?

My hope was that it would allow the reader the frisson of being in the presence of unreliable narrators. I wanted the reader to experience a charge from never being sure whether they're getting the whole truth, and never being sure whether the characters are deluding themselves into, or cheating themselves out of, something. I wanted the reader to be able to listen to Frances and Bernard as if they were jurors hearing testimony. Is she being overly cautious? Is he being overly optimistic, and how much of that optimism can be attributed to his illness?

How do you think this story would have developed if Frances and Bernard were living in 2013, with e-mail and texts?

My first impulse is to say it would not have developed! I only half-joke. Well, it might have developed along similar lines if the story took place in 1998, when, it seems to me, people still used e-mail to write long letters. Do people still use e-mail to write long letters now? They're probably Skyping instead. I know this is going to make me sound like a reactionary crank who fears progress, which means that I need to come clean and admit that writing Frances was not a stretch, but I don't think texting is a way to illuminate anything but your own sense of humor and how late you're going to be for brunch. As a human tracking device, texting is without peer. But it's an empty form of communication.

|

| photo: James Burke |

The "nunnery" where Frances lives in New York City, with all its colorful and disappointed women, sounds like a rich enough subject for a novel on its own. Was it inspired by a real place?

It was inspired by a real place, or real places, to be more accurate. Around the end of the 19th century, when single girls where leaving their homes to come work in cities, benevolent societies or other organizations created women-only residences where, for a reasonable fee, girls could have a room, three hot meals, and the security of knowing that they could keep themselves clean of the literal and figurative dirt of the city. I've had a fascination with them because they're secular nunneries, strange sororities. Frances lives in a place modeled on the Barbizon, which was one of the most famous women-only residences in New York. It was on the Upper East Side. Women like Grace Kelly and Sylvia Plath stayed there--Plath called it the Amazon in The Bell Jar. It's now, of course, a luxury apartment building.

Frances and Bernard are both so fully realized as characters that they evoke a complex response from the reader, as real people often do. Neither is easy to like or to get to know. How did these characters take shape for you?

They took shape first as voices. One passionate, one aloof. With Bernard, I wanted to capture Lowell's blustery, generous confidence and fearlessness, and with Frances I wanted to see if I could approximate the mix of wisdom and an almost juvenile kind of crank found in O'Connor's letters. I tried to play these voices like instruments, always asking myself whether I was about to hit a note that would ring false.

Then I sketched out a story that would put those temperaments in conflict in a believable but dramatic way, hoping that the voices would be amplified at crucial moments, and as a result you'd see their characters more clearly. To sketch that story I drew on the struggles experienced by Lowell and O'Connor, and then let myself run toward an obsession or fascination I wanted to explore, or question I wanted to answer. --Ilana Teitelbaum

Carlene Bauer: Temperaments in Conflict

Peeking into a stranger's mail suggests a surreptitious intimacy, and Annie Barrows and Mary Ann Shaffer's beloved 2008 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society epitomizes the epistolary form. Letters and telegrams fly across the English Channel between author Juliet and the charming citizens of Guernsey, so recently deprived of communication during the World War II Nazi occupation of their island.

Peeking into a stranger's mail suggests a surreptitious intimacy, and Annie Barrows and Mary Ann Shaffer's beloved 2008 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society epitomizes the epistolary form. Letters and telegrams fly across the English Channel between author Juliet and the charming citizens of Guernsey, so recently deprived of communication during the World War II Nazi occupation of their island.