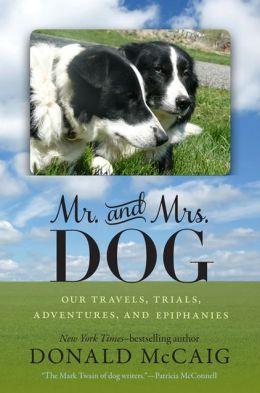

In Mr. and Mrs. Dog: Our Travels, Trials, Adventures, and Epiphanies (our review is below) Donald McCaig takes readers along on his journey to the World Sheepdog Trials with border collies Luke and June, juxtaposed with interviews with pet dog trainers of various methods. McCaig is the author of Civil War-era historical novels such as Rhett Butler's People, as well as canine-focused fiction and nonfiction. He lives on a Virginia sheep farm, but spoke with us from Seattle, where he and his dog Fly competed in a herding trial.

In Mr. and Mrs. Dog: Our Travels, Trials, Adventures, and Epiphanies (our review is below) Donald McCaig takes readers along on his journey to the World Sheepdog Trials with border collies Luke and June, juxtaposed with interviews with pet dog trainers of various methods. McCaig is the author of Civil War-era historical novels such as Rhett Butler's People, as well as canine-focused fiction and nonfiction. He lives on a Virginia sheep farm, but spoke with us from Seattle, where he and his dog Fly competed in a herding trial.

What made you decide to interview pet dog trainers?

I say I'm a sheepdog trainer, not a pet dog trainer. Part of that is my respect for people who are good at it. All I have to do is train dogs. They've got to train people. That's a lot harder, you know?

They had things to say that helped me see my own dogs better. The main difference is that what I'm doing as a sheepdog trainer is absolutely dependent on the dog's genetics, whereas a lot of what they're doing is against the dog's genetics. There's nothing in the dog's genetics that says it's a real good idea to walk right beside the pack leader with your nose tucked against his leg.

|

| Fly |

Now, some sheepdog training is that way. Sheepdogs have to be trained to drive. They're genetically programmed to fetch. So you start out with the fetch because it's easier to work with the genetics. It's only after you've got a real bond with the dog and some commands on the dog that you start teaching it to drive.

Behesha Doan talked a lot about how the dog is trying to cooperate, and use that as a bargaining chip. We sheepdoggers have a very brief saying: "The dog isn't listening." Well, it can get interesting when you say, "WHY isn't that dog listening, given the fact that these dogs are bred to cooperate with us?"

What inspired the fascinating line of thought on the Lost Dog you discuss in Mr. and Mrs. Dog?

It struck me as weird that all three Semitic religions--Judaism, Mohammadism and Christianity--on the surface despise dogs. The Qu'ran has an exception for Salukis, and St. Christopher originally had the head of a dog, but as a general rule, they don't like dogs. That's odd because in the panoply of world religion, generally the dog is thought of pretty highly. The second thing that struck me was that our favorite dog story is the Lost Dog story: Lassie Come Home, The Incredible Journey, my own Nop's Trials. We don't tell many stories on ourselves where we look bad. John Wayne always triumphs, good wins over evil, but in these Lost Dog Stories, we look like insensitive jerks time after time after time. I began to think these two things had something to do with each other.

Writing and trialing both play immense roles in your life. How would you relate the two?

Writing and trialing both play immense roles in your life. How would you relate the two?

One of the things about writing is, you don't have to get it right. You can make some horrible mistake. You catch it in revisions and gradually winnow your stupidities out. There's certain kinds of mistakes you can't make with a dog. One of the pet dog trainers told me that border collies are what she calls "incident critical," which means that if you make a mistake, they learn it and repeat it three times before you have a chance to fix it.

On the other hand, if you approach dogs with good will and your ears open and get good advice, they usually work out. I am convinced that they want to do it [trialing] as well and beautifully as we want to do it. I don't think we make them do that. I think we can kind of awaken them, in the way that you teach scales to a musical prodigy.

Ralph Pulfer was for many years the best American sheepdog handler. Once when he was in his 80s, at the point that he had to ride his ATV to the handler's post, a bunch of fellas asked, "Ralph, how much of this do you understand?" He went back to his RV, and everyone else popped another beer. He came out, and he answered, "I figure I understand about 15% of it." And here was a guy who'd been doing it for 50 years at the highest levels! That's wonderful. I really like to think that in the next years that I have to live, there are new worlds to understand about how the dogs are thinking, and how they're reacting. There's a way in which I'm never gonna get on top of it, and I like that.

So with dog training, there's always somewhere new for you to go?

Always. Always.

--Jaclyn Fulwood, youth services manager, Latah County Library District; blogger at Infinite Reads

Donald McCaig: Always Somewhere New to Go

Caddying was my first "real job," for two perfect summers--beginning when I was 14--at a failing resort course. Memories of those times flooded back recently as I read An American Caddie in St. Andrews: Growing Up, Girls, and Looping by Oliver Horovitz, though my experiences have little in common with the author's amusing, insightful and unexpectedly compelling exploration of youth, age, class and the true meaning of the word "vocation."

Caddying was my first "real job," for two perfect summers--beginning when I was 14--at a failing resort course. Memories of those times flooded back recently as I read An American Caddie in St. Andrews: Growing Up, Girls, and Looping by Oliver Horovitz, though my experiences have little in common with the author's amusing, insightful and unexpectedly compelling exploration of youth, age, class and the true meaning of the word "vocation."

In Mr. and Mrs. Dog: Our Travels, Trials, Adventures, and Epiphanies (our review is below) Donald McCaig takes readers along on his journey to the World Sheepdog Trials with border collies Luke and June, juxtaposed with interviews with pet dog trainers of various methods. McCaig is the author of Civil War-era historical novels such as Rhett Butler's People, as well as canine-focused fiction and nonfiction. He lives on a Virginia sheep farm, but spoke with us from Seattle, where he and his dog Fly competed in a herding trial.

In Mr. and Mrs. Dog: Our Travels, Trials, Adventures, and Epiphanies (our review is below) Donald McCaig takes readers along on his journey to the World Sheepdog Trials with border collies Luke and June, juxtaposed with interviews with pet dog trainers of various methods. McCaig is the author of Civil War-era historical novels such as Rhett Butler's People, as well as canine-focused fiction and nonfiction. He lives on a Virginia sheep farm, but spoke with us from Seattle, where he and his dog Fly competed in a herding trial.

Writing and trialing both play immense roles in your life. How would you relate the two?

Writing and trialing both play immense roles in your life. How would you relate the two?