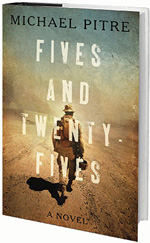

Michael Pitre is a graduate of Louisiana State University, where he was a double major in history and creative writing. In 2002, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. He deployed twice to Iraq and attained the rank of captain before leaving the service in 2010 to get his M.B.A. at Loyola University. Pitre lives in New Orleans with his wife. Fives and Twenty-Fives is his first novel.

Michael Pitre is a graduate of Louisiana State University, where he was a double major in history and creative writing. In 2002, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. He deployed twice to Iraq and attained the rank of captain before leaving the service in 2010 to get his M.B.A. at Loyola University. Pitre lives in New Orleans with his wife. Fives and Twenty-Fives is his first novel.

This novel involves a great deal of trauma, and one assumes you experienced similar trauma during your military service. Was your writing process cathartic, or painful?

My experiences in Iraq were pedestrian compared to those endured by the characters in this story. It's a book about people I knew and, in some cases, friends for whom I could have done more. That's the hidden pain of veterans, I think. We always remember the moments when we weren't brave, occasions when we didn't measure up, and days when we didn't give our best.

Catharsis came from a desire to do right by my friends. There were times when I knew exactly what would happen at the end of a paragraph, and I didn't want to finish it. Yes, it was painful. Had this book been easy to write, it would not have told a true story.

You point out that this is not a memoir, but you have a great deal in common with Lieutenant Donovan. Were the boundaries between fact and fiction always clear to you as you wrote this book? Did those boundaries turn out as you'd intended?

Early on, I was hyper-focused on maintaining a bright line between fact and fiction. Again, I set out to write a story that would honor the people I knew, and I'd hoped to avoid autobiographical details entirely. Of course, writing is a process. What crept into Donovan's character from my own experiences were mostly his feelings of inadequacy as an officer, and the awkwardness of being a young veteran in graduate school where classmates ask you to tell stories they aren't prepared to hear.

Are there any misconceptions about the war in Iraq that you felt you had to guard against?

I was eager to shun misconceptions about war in general, particularly when it came to glamour and gallantry. War is work. For the average U.S. service member in Iraq, it was filthy and exhausting, absurd and terrifying, repetitive and boring. That's why I chose road repair as the principal mission of Donovan and his Marines. It wasn't a sexy gig, but I don't know of another task in Iraq that was more dangerous or more necessary.

On the home front, I was wary of the giving the impression that Iraq War veterans are damaged goods. The young men and women who fill the ranks of the U.S. military are devoted professionals.

Though the characters in this story are struggling to reintegrate to civilian life, they aren't giving up, they aren't blaming anyone, and they aren't victims. They're working through their problems, and in the end, they're doing it together.

Who is the hero of this story? Or, your hero?

All three narrators are young men placed in impossible circumstances, and none of them come away clean. Even Donovan, who's all but bestowed with the formal title of hero, knows the truth about himself. The title becomes his burden.

The closest thing this story has to a hero is Sergeant Gomez. I've known a few Marines like her. I'd say they're my heroes.

I'm so glad you said that. She is so much more than the "token female" that she might have been in lesser hands. Her presence as the only woman in the platoon felt very natural. Does your experience bear out her ease in this story?

The short answer is yes, it's perfectly normal for a female sergeant like Gomez to run a road repair crew. Most Marines wouldn't give it a second thought. Female service members have been fully integrated into occupational specialties such as military police, combat engineers and logistics for well over two decades, and these groups have spent as much time on the roads of Iraq and Afghanistan as anyone.

In fact, as the American experience in Iraq wore on, female service members became highly valued for cultural reasons. To avoid inflaming the population, male Marines were forbidden to search Iraqi women at security checkpoints. So, a task force of female Marines was assembled, trained in search techniques and deployed to check points throughout western Iraq. This ad hoc solution was eventually formalized into a program called "Lioness," in which every battalion in theater had to answer its "Lioness tax" by surrendering a number of female Marines for the duration of a deployment.

Lioness was so successful that the program was copied and expanded into Afghanistan. Infantry patrols were reinforced with Female Engagement Teams composed of six to 10 female Marines. While the grunts dealt with the Afghan men outside, the female Marines would take off their helmets, go into the houses and develop relationships with the Afghan wives, mothers and daughters.

I served in Iraq alongside a female sergeant named Sally Saalman, who was perhaps the most feared and respected Marine in our battalion. She'd served on a forerunner of Lioness in 2005, and had been badly wounded in a suicide attack that killed six service members, three male and three female. (Read more about that event here.)

That was her first deployment. We met on her third. When Saalman raised her voice, everyone around would shut the f*** up and listen.

When and why did you decide to switch voices between your three main characters?

From the beginning, I knew the story would require three different perspectives and that one had to be Iraqi. It's a long-ignored truth of war that warriors often suffer least. This is especially true in counter-insurgency, where the civilian population is the battlefield. The Iraqi people were the mission. I felt that not representing their experience with its own, distinct voice would've been narcissistic.

As for Donovan and Pleasant, I thought it important to show how some veterans have opportunities opened for them by their service, while others are left all but ruined by it.

Did you set out to write a book with a message or moral, or is this simply the story that you held inside yourself as a novelist?

I didn't set out to write a book with a message or a moral. This really was just a story I had to tell. But along the way, as the character of Dodge became very real to me, I stumbled across the idea of people finding each other in their shared frailty. We're at our most human when we can recognize our dread, and our weakness, in others.

For those who presume they have nothing in common with a kid from Baghdad, I'd hope that they finish this book having discovered that they have everything in common with him. --Julia Jenkins

Michael Pitre: At Our Most Human

In his essay "Books vs. Cigarettes," Orwell observes that "reading is one of the cheaper recreations.... And if our book consumption remains as low as it has been, at least let us admit that it is because reading is a less exciting pastime than going to the dogs, the pictures or the pub, and not because books, whether bought or borrowed, are too expensive."

In his essay "Books vs. Cigarettes," Orwell observes that "reading is one of the cheaper recreations.... And if our book consumption remains as low as it has been, at least let us admit that it is because reading is a less exciting pastime than going to the dogs, the pictures or the pub, and not because books, whether bought or borrowed, are too expensive."

Michael Pitre is a graduate of Louisiana State University, where he was a double major in history and creative writing. In 2002, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. He deployed twice to Iraq and attained the rank of captain before leaving the service in 2010 to get his M.B.A. at Loyola University. Pitre lives in New Orleans with his wife. Fives and Twenty-Fives is his first novel.

Michael Pitre is a graduate of Louisiana State University, where he was a double major in history and creative writing. In 2002, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. He deployed twice to Iraq and attained the rank of captain before leaving the service in 2010 to get his M.B.A. at Loyola University. Pitre lives in New Orleans with his wife. Fives and Twenty-Fives is his first novel.