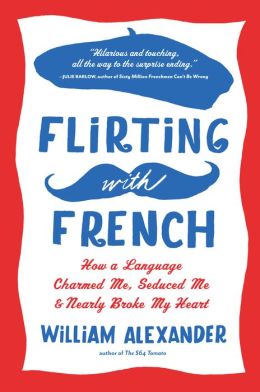

_J_Ferrara_Photography.jpeg) William Alexander is a journalist, memoirist and author of The $64 Dollar Tomato and 52 Loaves of Bread. In his new book, Flirting with French (our review is below), Alexander regales readers with anecdote after anecdote about the trials of mid-life language learning, while offering a crash course in the current science of second-language acquisition, the history of France (and the French language), and even a helpful flowchart guiding us through the labyrinthine social rules which govern the use of the French pronouns tu and vous.

William Alexander is a journalist, memoirist and author of The $64 Dollar Tomato and 52 Loaves of Bread. In his new book, Flirting with French (our review is below), Alexander regales readers with anecdote after anecdote about the trials of mid-life language learning, while offering a crash course in the current science of second-language acquisition, the history of France (and the French language), and even a helpful flowchart guiding us through the labyrinthine social rules which govern the use of the French pronouns tu and vous.

Obviously, learning French has been on your mind for some time. Were you always intending to write the book that Flirting with French became? In what ways did the project change over time?

It's hard to fathom now, and I feel foolish confessing this, but my original proposal for Flirting (working title: My Fair Frenchman) was that I, like Eliza Doolittle, would master enough of the language in only six months (or nine months at most, I stated), to "join French society," by which I meant hanging out in cafés and attending parties at which I'd join in on discussions on French politics and philosophy. (I wasn't starting from scratch; I'd had four years of French some 40 years earlier.) I fully expected to write a tale of triumph and fluency, not of failure and incoherence.

Why do you think that France holds so much romantic appeal for Americans? Why don't we feel the same way about Madrid or London as we do about Paris?

My theory is that Ernest Hemingway planted the seed of this idealized image of Parisian bonhomie and café life in The Sun Also Rises, and Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron watered it with An American in Paris. Not to mention all those GIs returning from the wars with their tales of free love and French kissing. But there truly is something special about Paris, bisected by the Seine and anchored by the Eiffel Tower. How can you not love a city whose openly gay and openly socialist mayor turns the banks of the Seine into a beach every summer? That boasts a boulangerie on every corner? Whose broad avenues are lined with outdoor cafés, where for the price of a single drink, you can linger all day? Where hidden pocket parks, fountains and statues abound? In sum, it's a very civilized place, from the architecture to art to the food, and I think Americans respond to that.

You had a terrible experience with French in high school. What are your thoughts now, after returning to language study as an adult? Should all children be exposed to a second language in school?

You had a terrible experience with French in high school. What are your thoughts now, after returning to language study as an adult? Should all children be exposed to a second language in school?

Without a doubt, all American children should receive second-language instruction in school (just not from my teacher, the sadistic Madame D---), and the younger they start, the more success they'll have. Besides the obvious cultural reasons to learn a foreign language, and the importance of broadening young (and old) minds, the cognitive benefits of bilingualism are finally coming to be recognized. And those benefits carry far beyond childhood. A recent study found that the onset of dementia or Alzheimer's occurs, on average, three years later among bilinguals than in monolinguals. If you teach foreign language properly in elementary and secondary school, you don't need to require that students continue it in college--that advanced study can be reserved for those who want to pursue foreign studies or, for example, read Proust in French. Although reading Proust in English is hard enough.

You mention Camus, Proust and Molière, among other French writers. As a writer and reader yourself, have you ever tried to read French literature in the original? How has studying the language changed your view of the many French translations you've read?

In fact, one of my motivations for learning French was to be able to read the classics in the original. But when I tried, I ran into an unexpected obstacle that no one had warned me about: the passé simple. This past tense, while little used today, was once used universally in written French, while the common passé composé, which is what all French-language students learn, was reserved for spoken French. That's right, the French have two past tenses: one for formally written, one for spoken French. And the passé simple often has inscrutable conjugations, which makes reading Balzac très difficile. (Plus you need to have a really extensive vocabulary to read even Le Petit Prince.) That being said, I was thrilled that I succeeded in reading Jean-Paul Sartre's short play The Reluctant Prostitute in the original, with the help of an English-language version and a French-English dictionary. Reading it in French reveals just how much you miss in translation. For example, the play opens with a man at the door of a prostitute. He addresses her as vous, while she uses the informal tu with him. This brought me to a dead stop. I thought I knew something about the informal, but who would call a prostitute vous while being called tu? A Noir (black man), that's who. Just think of all the social nuances that have been lost in the English translation of both vous and tu to "you," including the critical piece of information that a black man was on a lower social rung than a prostitute. Additionally, it wasn't until I learned some French that I realized how many words are left out of subtitles. Sometimes I'm able to catch the additional dialogue, and while it may not be critical to the plot, there is definitely something lost in the truncation and translation. It's akin to listening to Beethoven over AM radio. I shudder to think how some of the great dialogue from American films gets condensed in foreign releases. Did Rhett Butler's "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn," become simply "Je ne m'inquiète pas" in France?

You experienced some very serious health problems while writing the book. In what ways is this a book about aging and midlife in addition to being a book about language?

While my health issues certainly didn't make things any easier, they're not an excuse. Let's face it, I wasn't going to learn French in any event. But for me, the issues of health and aging and challenging your brain are inseparable. The (wholly self-induced) pressure to learn French may well have contributed to my heart irregularities; likewise, my intense study seems to have reversed some of my previous cognitive declines due to aging, so by necessity it's a book about all three issues. Early drafts left out the heart irregularities and my brush with la mort entirely, because it was something I didn't particularly care to discuss or revisit, and certainly not capitalize on, but the book seemed incomplete without it--as if I'd held something back. Because, well, I did. So in the end, with the encouragement of my editor, Amy Gash, I included it, and aside from it completing the story, I'm hoping that people with similar heart arrhythmias will get something from it.

How did this experience compare to writing The $64 Tomato and 52 Loaves?

A friend of mine described Flirting as The $64 Tomato with Frenchmen instead of groundhogs. Honestly, I was totally surprised when the first jacket blurbs and reviews came in using descriptions like "hilarious." At the time, trying to learn French didn't seem so funny. While all three books share the characteristics of being part memoir and part research, part humorous and part serious, Flirting and 52 Loaves were created in a drastically different fashion from Tomato, which was written retrospectively, and without a publisher, agent or editor. I define "innocence" as not having a book contract.

Do you have a favorite moment from your year of French that didn't make it into the book?

The hardest "French moment" to leave on the cutting-room floor was a chapter about my visit to the Frenchiest Town in America: Madawaska, Maine, about a hundred miles farther north than Montreal, where, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, a remarkable 83% of its families spoke French as their first language. Learning about the twice-exiled French settlers known as the Acadians, the attempts of the Maine KKK (which boasted a larger membership than Mississippi!) to rid Maine of French, and the current struggle of the ninth- and 10th-generation descendents to hang onto their heritage and language is a fascinating and poignant story, but Flirting just wasn't the right place to tell it. C'est la vie! --Emma Page, bookseller at Island Books, Mercer Island, Wash.

William Alexander: Flirter avec le français

_J_Ferrara_Photography.jpeg) William Alexander

William Alexander You had a terrible experience with French in high school. What are your thoughts now, after returning to language study as an adult? Should all children be exposed to a second language in school?

You had a terrible experience with French in high school. What are your thoughts now, after returning to language study as an adult? Should all children be exposed to a second language in school?