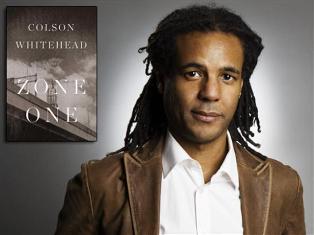

When you finish Zone One by Colson Whitehead (and you will, you will), you may want to ask him this question: Was the entire novel an extended joke straining toward that perfect punchline?

Whitehead, speaking by phone from his home in New York City, giggled (yes, he giggles) and said, "Basically, yes. I started writing this book in the summer of 2009. I came up with that last line on my first day working on it and wound up writing toward that the entire time. It was in line with my sense of humor and the kind of stuff I have going on in my other books."

Did it derail him? "Not at all. Once you have an idea like that so early, it's part of the character of the book. Look, I veer from the horrible and the bleak to the weird and the comic to the absurd to differing degrees in all of my books. I'd had to accept that I'm going to go there, toward something that veers wildly from despair to hope."

Did it derail him? "Not at all. Once you have an idea like that so early, it's part of the character of the book. Look, I veer from the horrible and the bleak to the weird and the comic to the absurd to differing degrees in all of my books. I'd had to accept that I'm going to go there, toward something that veers wildly from despair to hope."

Zone One (Doubleday) is Whitehead's just-released "zombie novel," one that encompasses a mere three days in the life of a "sweeper" nicknamed Mark Spitz who is assigned, along with his fellows, to rid post-apocalyptic Manhattan of any remaining "skels" (infected undead) and "stragglers" (infected humans caught in a sort of catatonia). It's filled with shooting, biting, tearing, running, screaming, jumping good fun.

So is Whitehead "genre jumping?" After all, his last novel, 2009's Sag Harbor, was a wry coming-of-age story set in the predominantly African-American resort of the title during the summer of 1985. "I don't see it as jumping," Whitehead said. "I grew up reading a lot of comic books and horror and Stephen King. Until I got to college I wanted to write about vampires and werewolves. I don't see distinctions as useful. I think you should read what you like and not worry about whether it's high or low brow."

Ultimately, he said, "I wanted to pay tribute to my childhood influences--and that opportunity turned out to be six books in." Whitehead said that after finishing Sag Harbor, "I blew a gasket and didn't write for two years. This little alarm goes off in your head as you try old ideas--'Maybe this is a little too similar to Apex Hides the Hurt'--and that makes me weary. I spent years writing my previous books, and to go back to something that overlaps is a little frustrating."

How much did he write in those two years? "Maybe 40 pages of journalism--not a lot!" he admitted. "I was reading, recharging and vegging out. I'm pretty happy doing that. If it turned out to be five years, I might get a little anxious."

With other books, Whitehead said, his ideas came from magazine articles, or even the news, "The Intuitionist actually came from a piece about an escalator inspector done by Hugh Downs, which tells you a bit about how far back that was." However, for Zone One, the inspiration was as close (and as far) as childhood. "The terror of zombies has stayed with me since junior high, and it has nothing to do with their masticating destruction. The terror is that your nearest and dearest have, overnight, turned into the monsters that they have always been in your nightmares! That was my sick Freudian interpretation of what zombies were when I was 13."

As for writing about a post-apocalyptic New York City, the author pointed out that "New York in the 1970s was a pretty deplorable place, and that '70s city is part of this book. I'm paying tribute to another strain from my childhood, too: all of those Cold War, nuclear holocaust films like Escape from New York, Planet of the Apes and Damnation Alley. I decided that in a post-apocalyptic world that's trying to crawl back to stability, like the one in my book, the worst things would come back quickly--marketing, propaganda. They are so hardwired into our modern personality."

Was it fun writing gory scenes? "Yeah, well, it's great to think that maybe readers will enjoy it--but it's terrible to write a book! It's finding the words and slogging through. Mostly there's just a lot of coaxing horrible sentences into less horrible shape." However, he admitted that some scenes are more meaningful to him than others: "The scenes that Mark Spitz has in an abandoned toy store with a woman he meets named Mim--those are important. Because then he has a companion, the chance of a new start. You have to be able to believe in the refuge, the safe haven, or else why are you walking around at all?"

He continued, "Maybe 10 years ago, if I had been writing this, some of the sweepers would have been more caricaturish. Now, well, they're real people. Mark Spitz is trying to find a new family for himself to replace the one he lost. He wants to make a new social order in the ruins, find an animating bond that is important."

Why write these characters now? Whitehead giggles again, presaging an admission: "Being a father has changed the way I move in the world. Fatherhood [his daughter is seven] gives me a different perspective on my family and the generational process. I used to joke that when a character had his head blown off that 'it was only a flesh wound!' but now, the ones who die? It's a little more poignant."

He giggled again. "I'm still killing them off, but they're, you know, differently textured than they were before." Colson Whitehead, it seems, cannot resist a punch line. --Bethanne Patrick

Portrait of the Artist: Colson Whitehead

Did it derail him? "Not at all. Once you have an idea like that so early, it's part of the character of the book. Look, I veer from the horrible and the bleak to the weird and the comic to the absurd to differing degrees in all of my books. I'd had to accept that I'm going to go there, toward something that veers wildly from despair to hope."

Did it derail him? "Not at all. Once you have an idea like that so early, it's part of the character of the book. Look, I veer from the horrible and the bleak to the weird and the comic to the absurd to differing degrees in all of my books. I'd had to accept that I'm going to go there, toward something that veers wildly from despair to hope." One of the most intriguing books we've read this fall is The Maid: A Novel of Joan of Arc by Kimberly Cutter. While the Roman Catholic St. Joan has been much celebrated in song, story and even on film (as recently as 1999's The Messenger, starring Milla Jovovich, who does bear an uncanny resemblance to the Pre-Raphaelite Joan on Cutter's cover), few fiction writers have had success telling her story in a vital way.

One of the most intriguing books we've read this fall is The Maid: A Novel of Joan of Arc by Kimberly Cutter. While the Roman Catholic St. Joan has been much celebrated in song, story and even on film (as recently as 1999's The Messenger, starring Milla Jovovich, who does bear an uncanny resemblance to the Pre-Raphaelite Joan on Cutter's cover), few fiction writers have had success telling her story in a vital way. The Journal of Hildegard of Bingen: Inspired by a Year in the Life of the Twelfth-Century Mystic by Barbara Lachman is an entirely fictional memoir based on Lachman's extensive studies into the life of St. Hildegard, whose mystical visions from childhood were not recorded until she was in middle age. An abbess and healer, she was also a musical composer whose songs are still performed and recorded. The author structured her Hildegard's "year" around the early Christian liturgical calendar, and gives voice to a pre-Renaissance "Renaissance woman."

The Journal of Hildegard of Bingen: Inspired by a Year in the Life of the Twelfth-Century Mystic by Barbara Lachman is an entirely fictional memoir based on Lachman's extensive studies into the life of St. Hildegard, whose mystical visions from childhood were not recorded until she was in middle age. An abbess and healer, she was also a musical composer whose songs are still performed and recorded. The author structured her Hildegard's "year" around the early Christian liturgical calendar, and gives voice to a pre-Renaissance "Renaissance woman." Sarah Dunant's Sacred Hearts is largely set in a 16th-century Italian convent, and there are star-crossed lovers involved--but that's where any similarity to historical weepies about locked-up debutantes and their valiant princes ends. Dunant, an exceptional researcher and sensitive writer, sets the love story and its unlikely duenna, Suora Zuana, firmly in the context of the Roman Catholic church of that time period, filled with politics, intrigue and scandal.

Sarah Dunant's Sacred Hearts is largely set in a 16th-century Italian convent, and there are star-crossed lovers involved--but that's where any similarity to historical weepies about locked-up debutantes and their valiant princes ends. Dunant, an exceptional researcher and sensitive writer, sets the love story and its unlikely duenna, Suora Zuana, firmly in the context of the Roman Catholic church of that time period, filled with politics, intrigue and scandal. Miracles: A Novel by Marcy Heidish is about Mother Elizabeth Seton, the first U.S. citizen to be canonized as a Roman Catholic saint. Elizabeth Ann Seton was born and raised in the Episcopal Church. She married and had five children, but after her husband died in 1802, Seton converted to Catholicism. Due to anti-Catholic sentiment, she moved from New York City to Maryland and founded a school in Emmitsburg. She was canonized in 1975 and is considered the patron saint of Catholic schools. --

Miracles: A Novel by Marcy Heidish is about Mother Elizabeth Seton, the first U.S. citizen to be canonized as a Roman Catholic saint. Elizabeth Ann Seton was born and raised in the Episcopal Church. She married and had five children, but after her husband died in 1802, Seton converted to Catholicism. Due to anti-Catholic sentiment, she moved from New York City to Maryland and founded a school in Emmitsburg. She was canonized in 1975 and is considered the patron saint of Catholic schools. -- ---

---