|

| photo: Rebecca Hale |

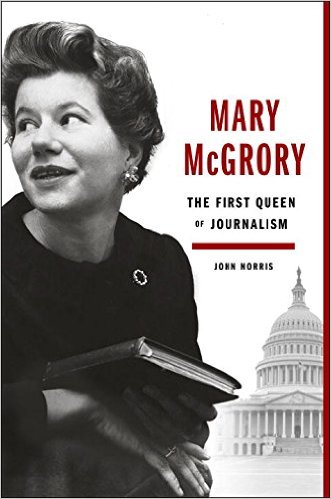

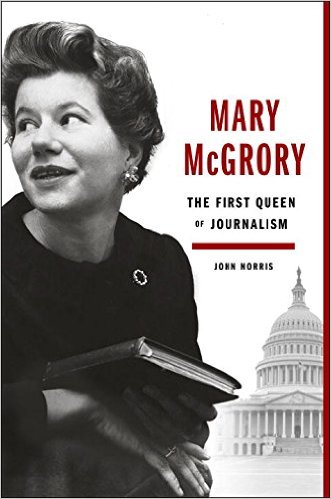

John Norris is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington, D.C. He has a graduate degree in public administration and has served in senior roles in government, international institutions and nonprofits, including with the United Nations, the State Department and the International Crisis Group. Norris has written for the Atlantic, the Washington Post, Foreign Policy and many other publications. He is the author of The Disaster Gypsies, a memoir of his work in the field of emergency relief, and Collision Course: NATO, Russia and Kosovo. His new book is Mary McGrory: The First Queen of Journalism (reviewed below).

When did you first learn about Mary McGrory, and when did you know you would write a book about her?

I knew Mary personally a little bit. I was working in the State Department [during the Clinton administration] and she would call to pick my brains some. I also, like so many others, got dragooned into volunteering at St. Ann's [Infant and Maternity Home] and helping out with the Christmas and St. Patrick's Day parties. I got invited to a couple of social gatherings at her house, so I got to experience both her organizing touch and her parties and bad cooking. At one party, Roger Mudd and I were in charge of fixing drinks for people. I was pretty young and fairly new to Washington, so the idea of serving cocktails with a legendary CBS anchorman was something. But at one point we looked and the ginger ale had gone quite bad. There was kind of a mossy substance growing on top of it. And Roger Mudd turned to me and said, you have to tell Mary. And I said, I'm not going to tell Mary! You tell Mary! So we argued like 5th graders about it... and then we decided we would just tell everybody there was no ginger ale.

But as I got to know Mary, I appreciated that there was a really good story there. It was kind of a Horatio Alger story, of somebody who worked her way up from not an awful lot to be very successful in what she did, but also that she had a fabulous, unique flair. After she had died, I started thinking about doing the book and poked around; it was probably about five years ago that I really began in earnest. It was much harder than I thought it would be to write, in some ways.

How long did that process take, from conception to a finished manuscript?

How long did that process take, from conception to a finished manuscript?

About five years. I've got three little kids--the oldest is seven and the youngest is a year old--so I was busy with them. I had just finished working in Nepal with my wife. And this was kind of a busman's holiday, because I've got a full-time job that doesn't deal with Mary McGrory or journalism particularly, as an international affairs expert. So there were a lot of competing challenges to juggle at the same time. I just chewed away on it, and by the time I'd sorted out a publisher, I had a finished book.

What were the research and writing phases like, and how did they play together?

You know, I imagine this is an experience that a lot of people have when they take on a biography or a historical project. At first, I was terrified that I wouldn't have enough material, that it would seem thin. And then suddenly I woke up one day and said, I've got way too many words, I've got way too much, how do I condense all this down and make sense of it?

It was very helpful that Mary donated her papers to the Library of Congress. There are 164 boxes of her material there: notebooks, articles, clippings and correspondence. Her family was quite good about sharing some other things they hadn't given to the library. I'd love to be one of those writers who, in a fit of passion, starts at sundown and hands the manuscript over as the sun comes up. But I nibbled away, stringing together passages, and the research and writing mixed together.

One of the really interesting things for me, having never written a biography, was being able to find data points, putting together three or four different things and then suddenly finding that there was a really interesting story there once you lined up all the dates and characters. My research style was to create a monstrously large chronology. I took everything in chronological order--interesting stuff from the columns, interesting stuff from interviews--and it started to make much more sense for me. For example, there had been a Time magazine profile on her not long after the Army-McCarthy hearings, and she got a ton of correspondence. But it was only after I had lined up some dates that I realized she had gotten four book offers from major publishers on the same day. She had never mentioned this to anybody, and nobody would have ever remarked or known it, without actually looking at her correspondence in a chronological fashion and jotting it down. Finding those kind of hidden nuggets was maybe the most rewarding part.

You seamlessly tie in the narrative of United States political history with the narrative of Mary's life.

As I was writing, I realized at some point that there were three books that I was trying to do at the same time. One was a history of Mary as a person, which obviously was the core that I really needed to get right. Second was a big swath of contemporary American history that I needed to weave in. And then the third strand was, what does this say about journalism? What does it say about women in journalism, and how that's evolved, and in some cases how it's not evolved a whole lot?

What part of Mary's story do you most identify with?

It would be easy to say that she wrote beautifully but it didn't come easy to her, she fretted and noodled and kept revising and rewriting and redoing her work. The other lesson that she really carried for me was, there weren't a lot of people who had faith in Mary. But she put her head down and kept at it. Even though she did have a big breakthrough with Army-McCarthy, she really had been toiling in near obscurity, wanting to cover politics for a long time by that point, and being politely but firmly being told no by a lot of people. But she kept at it, and she got a couple of stories, and when she had her chance, she really took it. I think that the persistence side of the story is one that is encouraging for any writer.

At the start of the book, it feels like you take an impartial outsider's perspective, but by the end, it feels more intimately connected to Mary's story. Was this intentional?

That's an interesting question. I think that part of that might be because I knew her later in life, and I got to talk to her contemporaries and people who had been around her. Interviewing them was an advantage for the later material. Writing about her childhood and those early parts, that probably always feels more removed in some ways. But I think it's also that you gain steam as you begin to explore a person and get to know them.

What in your background as a writer and as a political actor prepared you to tell this story well?

A couple different things. I've got three sisters, a strong-willed mother, a feisty wife and two very independent-minded young daughters, so that side of things certainly prepared me well. I've always been a bit of a political junkie. I write politics, I think it's interesting, and I understand people who think it's interesting, even when it's a guilty pleasure, whether that's Donald Trump or anything else. There are times when it is a noble calling, and then there are other times when it's like watching an entertaining car crash. I think that ability to talk about politics, and understand people who think and write about politics, served me well both in trying to decode Mary and in interacting with her fellow reporters and other people I interviewed as part of the research.

Getting to talk with the people in Mary's life was a great pleasure, just sitting down and talking to people and puzzling it through. You know, they say about fiction, and I think it's equally true of nonfiction, that you want to pick characters that you're not going to get bored with or tired of or angry at by the end of a project, and I never did with this one. I still have a bunch of questions I would love to ask her if I had a chance. It's been a great ride. --Julia Jenkins, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

John Norris: Taking Pleasure in the Right Subject

Food critic Rebekah Denn is struck by how many children's books are about food... all that meat-smoking in the Little House books, the Turkish Delight in Narnia. Chef Bridget Charters remembers seeing Mother Goose's "hot cross buns" at a San Francisco bakery, and rushing back to make them from The Joy of Cooking recipe. Chef Tarik Abdullah doesn't remember cookbooks, but does remember how his dad marketed sausage--with a picture of his own face. Kate Lebo (A Commonplace Book of Pie) talks about writing poetry and baking pie: "The difference is, my audience knows what to do with a pie." Edouardo Jordan of Salare Restaurant tells the room that he finally realized why his dad's version of "Little Red Riding Hood"--and all the other stories--was so different from his mom's: he couldn't read.

Food critic Rebekah Denn is struck by how many children's books are about food... all that meat-smoking in the Little House books, the Turkish Delight in Narnia. Chef Bridget Charters remembers seeing Mother Goose's "hot cross buns" at a San Francisco bakery, and rushing back to make them from The Joy of Cooking recipe. Chef Tarik Abdullah doesn't remember cookbooks, but does remember how his dad marketed sausage--with a picture of his own face. Kate Lebo (A Commonplace Book of Pie) talks about writing poetry and baking pie: "The difference is, my audience knows what to do with a pie." Edouardo Jordan of Salare Restaurant tells the room that he finally realized why his dad's version of "Little Red Riding Hood"--and all the other stories--was so different from his mom's: he couldn't read.

How long did that process take, from conception to a finished manuscript?

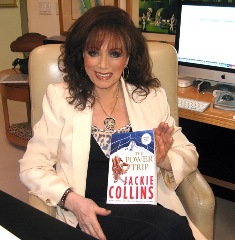

How long did that process take, from conception to a finished manuscript?  Collins wrote more than 30 books, "vibrant novels about the extravagance and glamour of life in Hollywood... many of them filled with explicit, unrestrained sexuality," the New York Times wrote in its

Collins wrote more than 30 books, "vibrant novels about the extravagance and glamour of life in Hollywood... many of them filled with explicit, unrestrained sexuality," the New York Times wrote in its