Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is the story of one fictional character, Captain Simone Simonini, whose creepy peregrinations through late 19th-century Europe in search of a loathsome document put him in contact with dozens of historical characters, nearly all of whom are as creepy as Simonini, if not as downright loathsome as the infamous forgery "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" (more on that document in a moment). Eco explained, "I had to tell a story about a repugnant character, but make readers want to keep learning his story. That isn't easy."

Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is the story of one fictional character, Captain Simone Simonini, whose creepy peregrinations through late 19th-century Europe in search of a loathsome document put him in contact with dozens of historical characters, nearly all of whom are as creepy as Simonini, if not as downright loathsome as the infamous forgery "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" (more on that document in a moment). Eco explained, "I had to tell a story about a repugnant character, but make readers want to keep learning his story. That isn't easy."

Eco is sitting across from me in the bar of the Jefferson Hotel in Washington, D.C., and the famous author himself is anything but repugnant. Just arrived from his home in Milan, Eco is nattily dressed, a small Dunhill cigar clamped in the corner of his mouth, an on-the-rocks martini (Sapphire gin, lemon twist) within reach. How, I asked him, did someone who clearly enjoys life and all of its trappings become so fascinated with writing about characters who only want to take life away from others?

He answered in perfect but richly accented English: "Because I am fascinated by lying! Humans lie. A dog does not lie! When a dog barks, it's for a reason. Lying is a feature of the human mind, and part of lying is forgery. Look, for many many years I have been interested in this document, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. We know it's a forgery, a complete fake--but not only did people believe it was true for decades, but even after it was proven false, an English writer named Nesta Webster wrote that even if it were a false document, that its statements were so accurate we might as well consider them the truth."

He answered in perfect but richly accented English: "Because I am fascinated by lying! Humans lie. A dog does not lie! When a dog barks, it's for a reason. Lying is a feature of the human mind, and part of lying is forgery. Look, for many many years I have been interested in this document, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. We know it's a forgery, a complete fake--but not only did people believe it was true for decades, but even after it was proven false, an English writer named Nesta Webster wrote that even if it were a false document, that its statements were so accurate we might as well consider them the truth."

Many readers will be aware of "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," the anti-Semitic text describing a purported Jewish plan for world domination; it was published in Russia in 1903 and used by Hitler and his cohorts to justify their actions against the Jewish race. In tracing a wholly fictitious path by which that document might have seen the light of day, Eco also traces the wholly historical path of a virulent strain of anti-Semitic thought that flourished in many nations otherwise considered "civilized." "I wanted to tell a story about how an enemy can be concocted out of almost nothing," Eco said. "All of the documents I talk about in this book, all of the characters except for Simonini--they are like pieces of different corpses that I put together, a sort of Frankenstein's monster of a story. I wanted it to be ugly and malformed. What these people did was ugly and malformed. They used whatever information they had about Jews not to clear away prejudice, but to reinforce it."

Eco talks about lying again, pausing to light a new cigar. "Think of the seller of used cars," he said. "It's no accident that people said of Nixon 'Would you buy a used car from this man?' The used-car salesman is a professional liar who will tell you not just what you want to hear, but whatever he thinks you need to hear. I wanted to write a book about liars that would not cheat the reader, would not rely merely on stock characters."

Since Eco spends a great deal of his time as a teaching and publishing academic, he plays games with himself as well as with his readers (who are accustomed to the wordplay, plot machinations and whimsicality of his prose from such works as The Name of the Rose and Foucault's Pendulum). "I always use some constrictions when I start a novel," he aded. "I set Baudolino during the Siege of Constantinople because I had never been to that city and it gave me an excuse to go. I had Simonini, in this book, visit the hospital of Sal Petriere to give me a reason to visit and learn more about it."

That isn't to say all of his narrative tricks work. "I must tell you of what is a great failure," Eco confessed, with a twinkle in his eye. "I meant all of Simonini's eating and restaurant visits to show him as a gross and greedy man--but after all of my research into those dishes and menus, readers keep asking me about them because they are interested in the food!"

Speaking of food, Eco is nursing a drink slowly and not eating because a few hours after our interview, he will be dining with colleagues prior to appearing at Politics & Prose. "I just got here, and then tomorrow I go to Philadelphia, and then...." He proceeds to name half a dozen stops in the States, then several in Canada, and a few in England. "I am a little bit discombobulated right now!" He laughs. "I love that English word, 'discombobulated.' That, and 'flabbergasted.' I think my readers will be discombobulated and flabbergasted by Simonini." --Bethanne Patrick

Portrait of the Artist: Umberto Eco

We've reviewed and covered in various ways some of the 20 NBA nominees--five in each category. There's a Book Brahmin with Téa Obreht, author of The Tiger's Wife, a fiction nominee. (She's a charming 26-year-old who has written an astounding first novel. An NBA award would be another milestone on the magical literary trip she has taken in the past several years.) We have reviews of The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt, a nonfiction nominee, and Chime by Franny Billingsley, nominated for the young people's literature award. In addition, we devoted a special issue to Okay for Now by Gary D. Schmidt, which includes a review and interviews with the author and his editor. Okay for Now is being considered for the young people's literature prize.

We've reviewed and covered in various ways some of the 20 NBA nominees--five in each category. There's a Book Brahmin with Téa Obreht, author of The Tiger's Wife, a fiction nominee. (She's a charming 26-year-old who has written an astounding first novel. An NBA award would be another milestone on the magical literary trip she has taken in the past several years.) We have reviews of The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt, a nonfiction nominee, and Chime by Franny Billingsley, nominated for the young people's literature award. In addition, we devoted a special issue to Okay for Now by Gary D. Schmidt, which includes a review and interviews with the author and his editor. Okay for Now is being considered for the young people's literature prize.

Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is the story of one fictional character, Captain Simone Simonini, whose creepy peregrinations through late 19th-century Europe in search of a loathsome document put him in contact with dozens of historical characters, nearly all of whom are as creepy as Simonini, if not as downright loathsome as the infamous forgery "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" (more on that document in a moment). Eco explained, "I had to tell a story about a repugnant character, but make readers want to keep learning his story. That isn't easy."

Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), is the story of one fictional character, Captain Simone Simonini, whose creepy peregrinations through late 19th-century Europe in search of a loathsome document put him in contact with dozens of historical characters, nearly all of whom are as creepy as Simonini, if not as downright loathsome as the infamous forgery "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" (more on that document in a moment). Eco explained, "I had to tell a story about a repugnant character, but make readers want to keep learning his story. That isn't easy." He answered in perfect but richly accented English: "Because I am fascinated by lying! Humans lie. A dog does not lie! When a dog barks, it's for a reason. Lying is a feature of the human mind, and part of lying is forgery. Look, for many many years I have been interested in this document, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. We know it's a forgery, a complete fake--but not only did people believe it was true for decades, but even after it was proven false, an English writer named Nesta Webster wrote that even if it were a false document, that its statements were so accurate we might as well consider them the truth."

He answered in perfect but richly accented English: "Because I am fascinated by lying! Humans lie. A dog does not lie! When a dog barks, it's for a reason. Lying is a feature of the human mind, and part of lying is forgery. Look, for many many years I have been interested in this document, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. We know it's a forgery, a complete fake--but not only did people believe it was true for decades, but even after it was proven false, an English writer named Nesta Webster wrote that even if it were a false document, that its statements were so accurate we might as well consider them the truth." 11/22/63 by Stephen King is a long-awaited and--at 944 pages--seriously long novel that combines suspense, the supernatural and superb storytelling powers with a history-jarring idea: What if President John F. Kennedy had not been assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas on November 22, 1963?

11/22/63 by Stephen King is a long-awaited and--at 944 pages--seriously long novel that combines suspense, the supernatural and superb storytelling powers with a history-jarring idea: What if President John F. Kennedy had not been assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas on November 22, 1963? For Want of a Nail by Robert Sobel: Sobel's Pulitzer-nominated novel is subtitled "If Burgoyne Had Won at Saratoga." What would the North American landscape look like under British rule that eventually fails, leaving a "Confederation of North America" at constant war with Mexico?

For Want of a Nail by Robert Sobel: Sobel's Pulitzer-nominated novel is subtitled "If Burgoyne Had Won at Saratoga." What would the North American landscape look like under British rule that eventually fails, leaving a "Confederation of North America" at constant war with Mexico? England, England by Julian Barnes: Literary novelist Barnes brilliantly pulls off an alternate-history-within-an-alternate-history, imagining an "All England" theme park on the Isle of Wight (a Harrods at the Tower!), contrasted with a newly rural near-future version of same.

England, England by Julian Barnes: Literary novelist Barnes brilliantly pulls off an alternate-history-within-an-alternate-history, imagining an "All England" theme park on the Isle of Wight (a Harrods at the Tower!), contrasted with a newly rural near-future version of same. The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson: If you read just one "alternate history" book, this should be it. Robinson, an acclaimed science-fiction author, reimagines the world after the 14th-century plague decimates Europe and other countries and cultures take center stage.

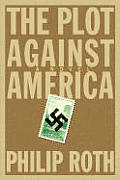

The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson: If you read just one "alternate history" book, this should be it. Robinson, an acclaimed science-fiction author, reimagines the world after the 14th-century plague decimates Europe and other countries and cultures take center stage. The Plot Against America by Philip Roth: A dark inversion in which President Lindbergh negotiates an "understanding" with Adolf Hitler--making life a terror for American Jews. --

The Plot Against America by Philip Roth: A dark inversion in which President Lindbergh negotiates an "understanding" with Adolf Hitler--making life a terror for American Jews. --