|

| photo: Jen Davis |

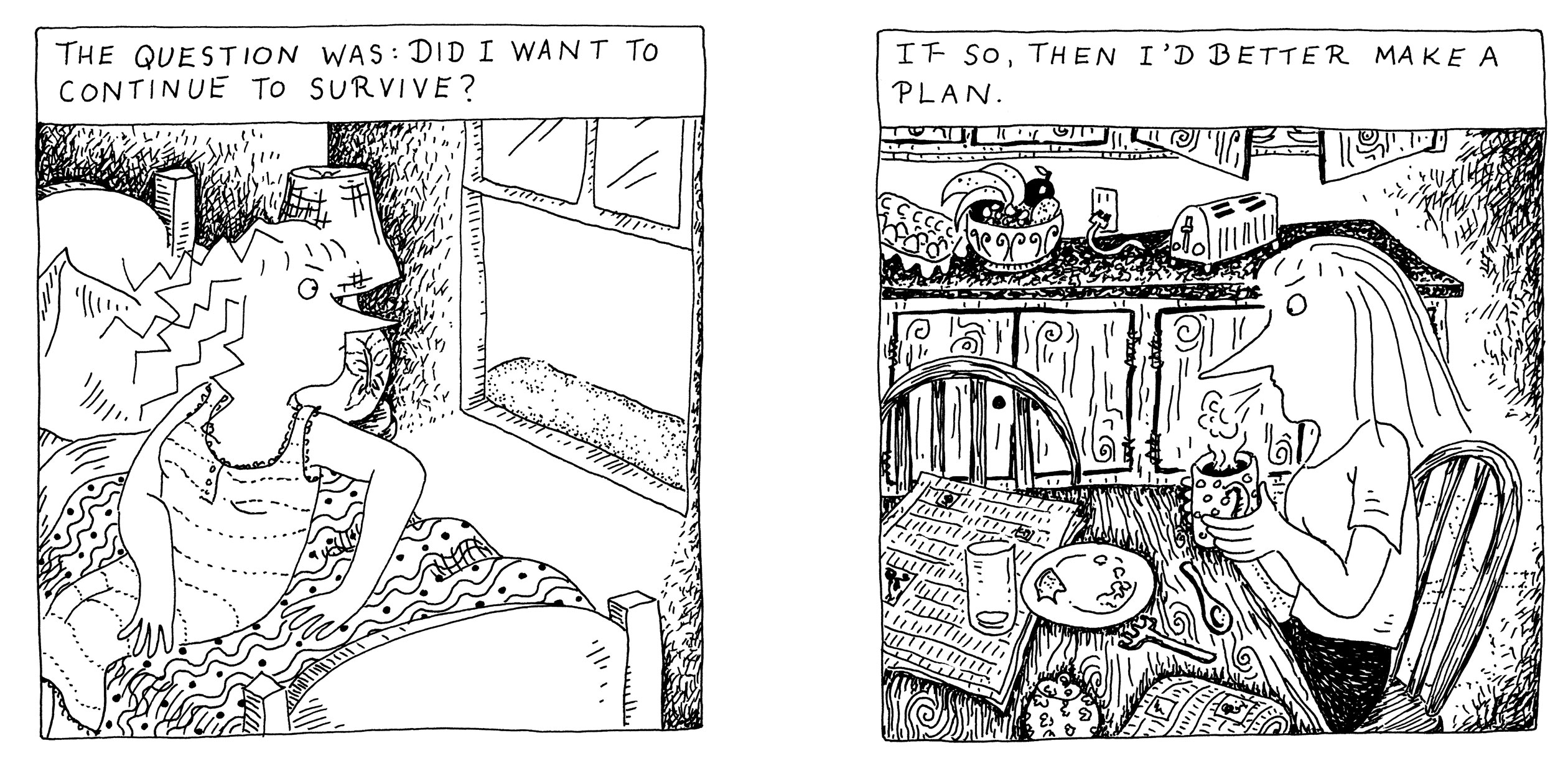

Jennifer Hayden is a cartoonist living in New Jersey. Underwire, Hayden's first collection of autobiographical comics, was named by DoubleX

as one of "the best comics by women" and excerpted in Best American Comics 2013

. Her webcomic S'crapbook

received a Notable listing in Best American Comics 2012

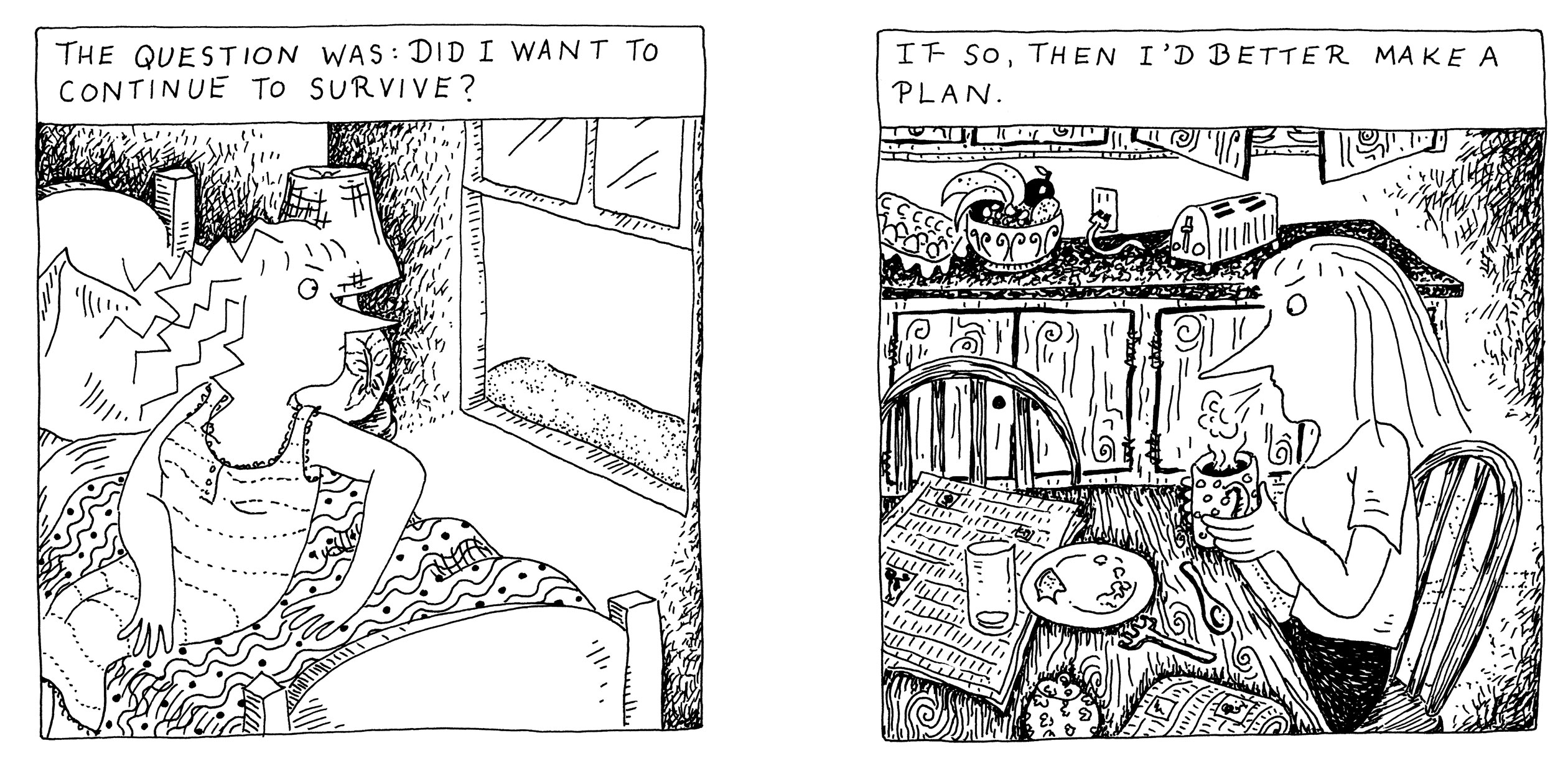

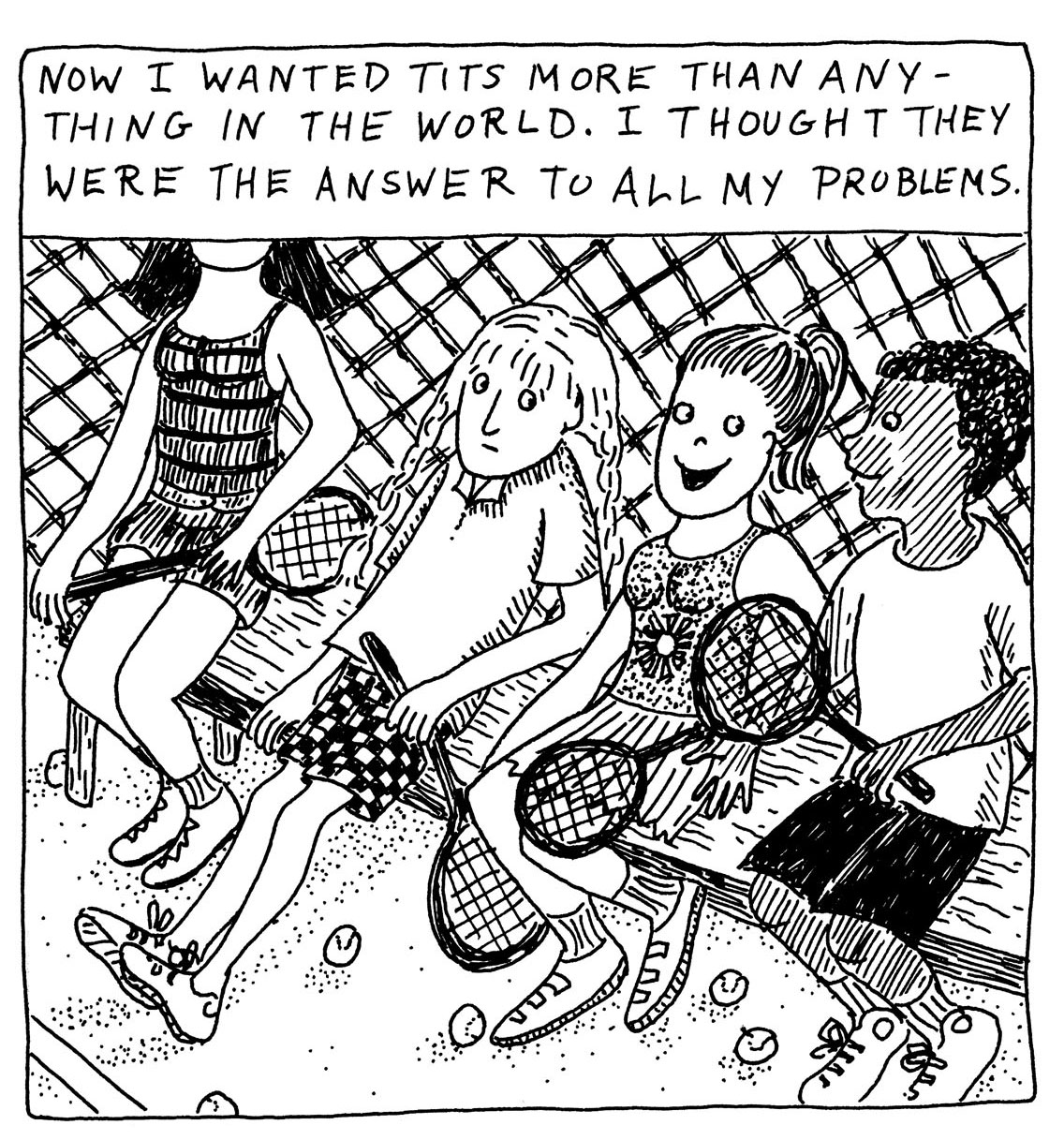

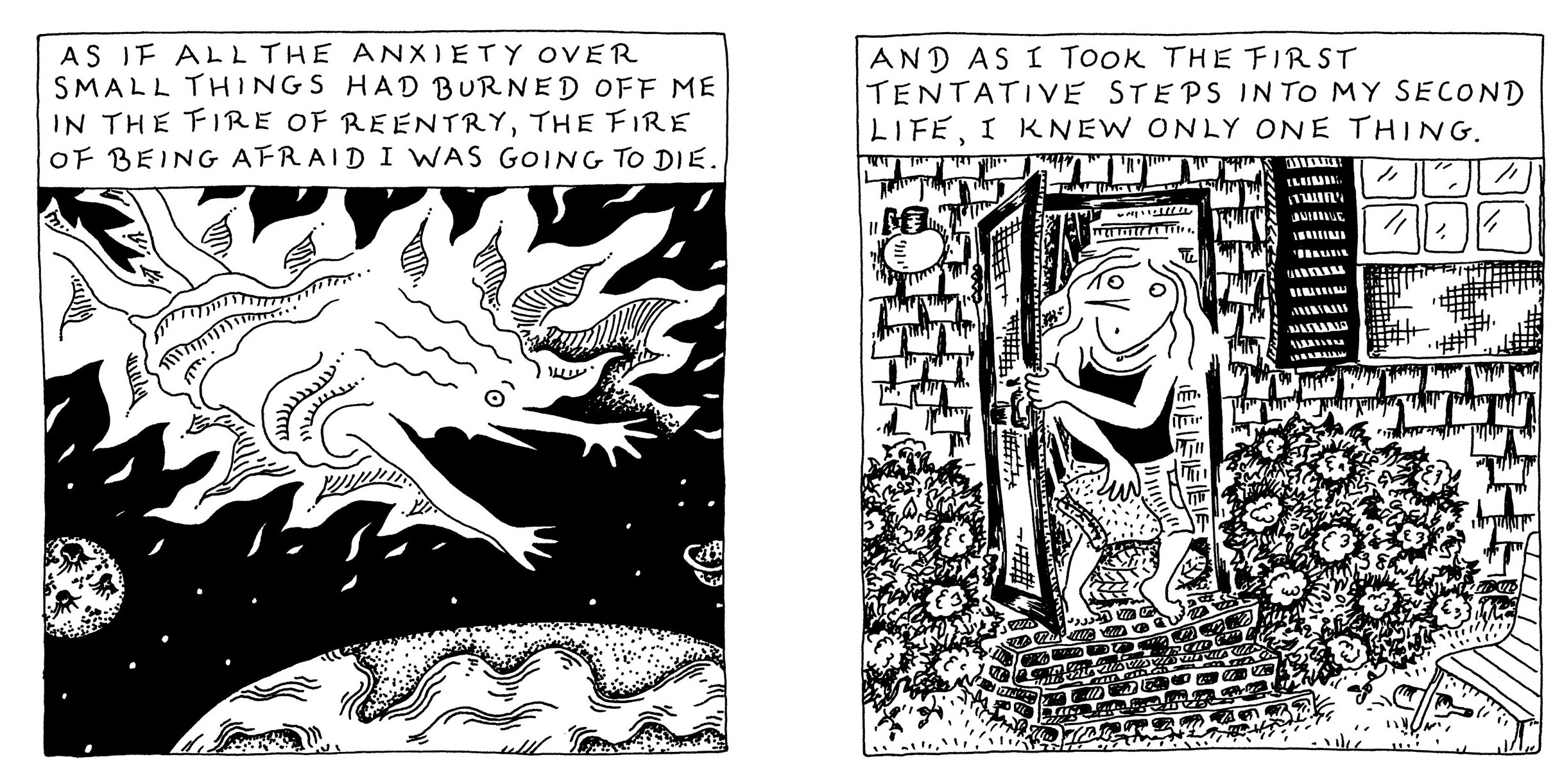

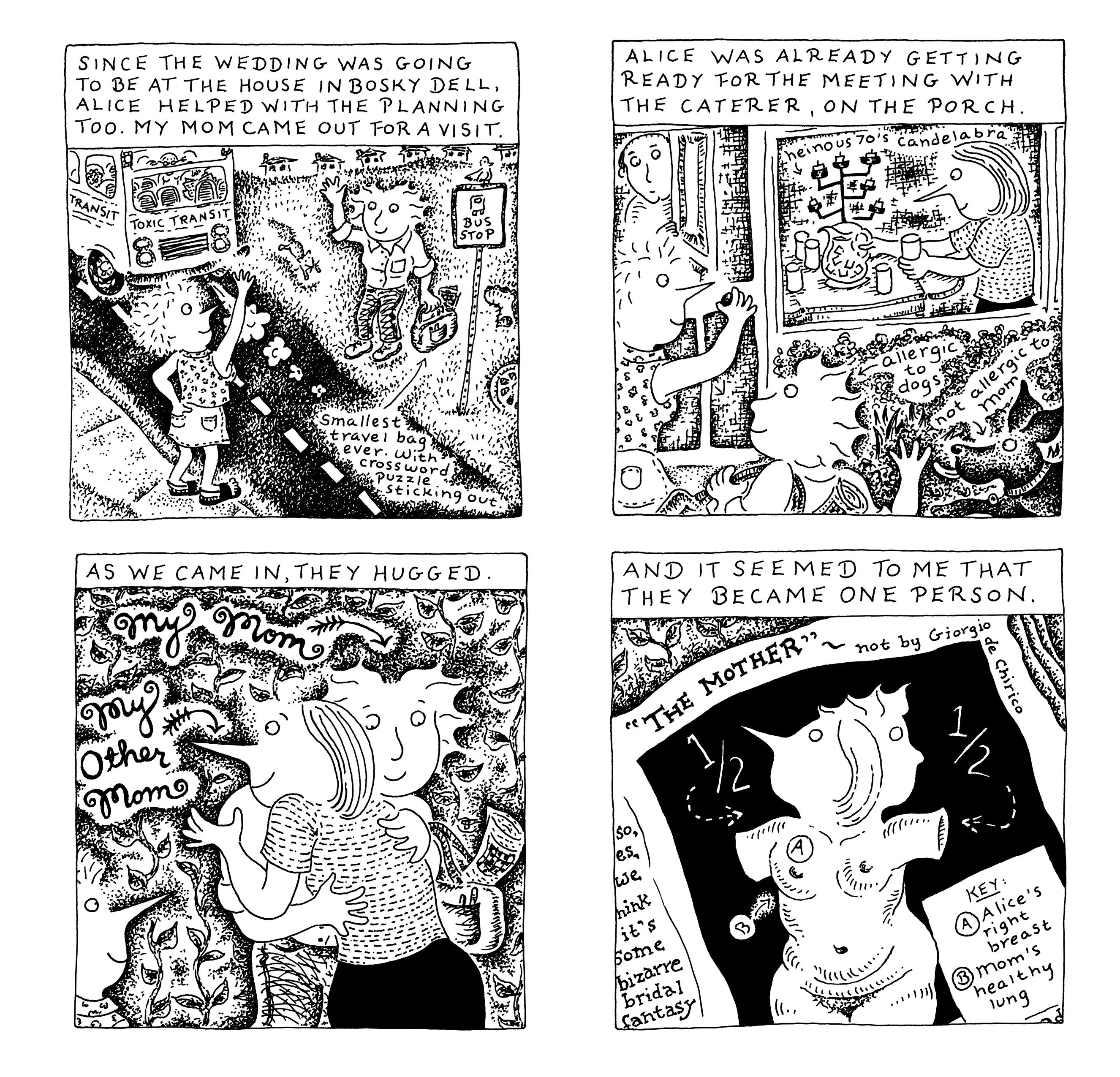

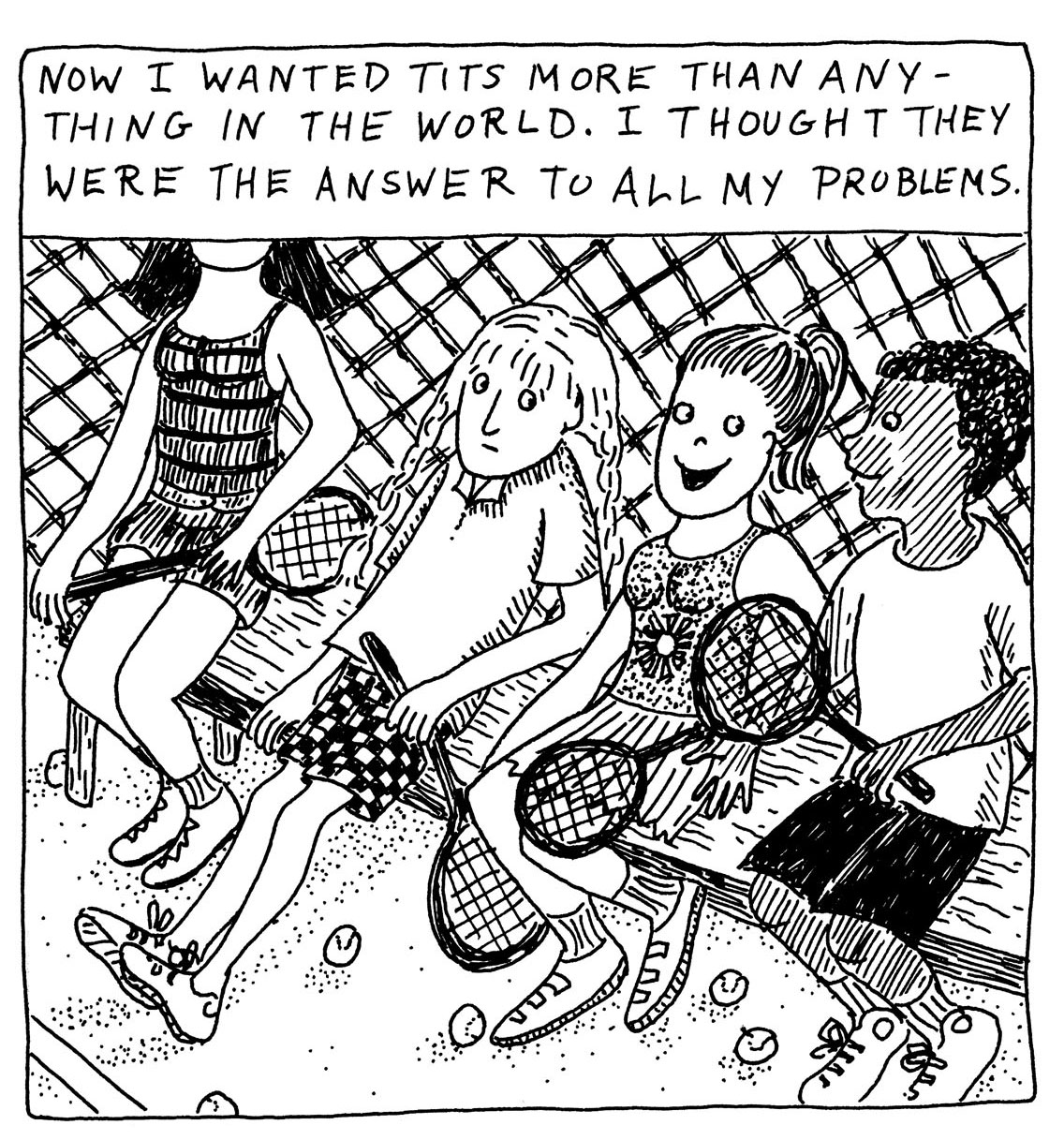

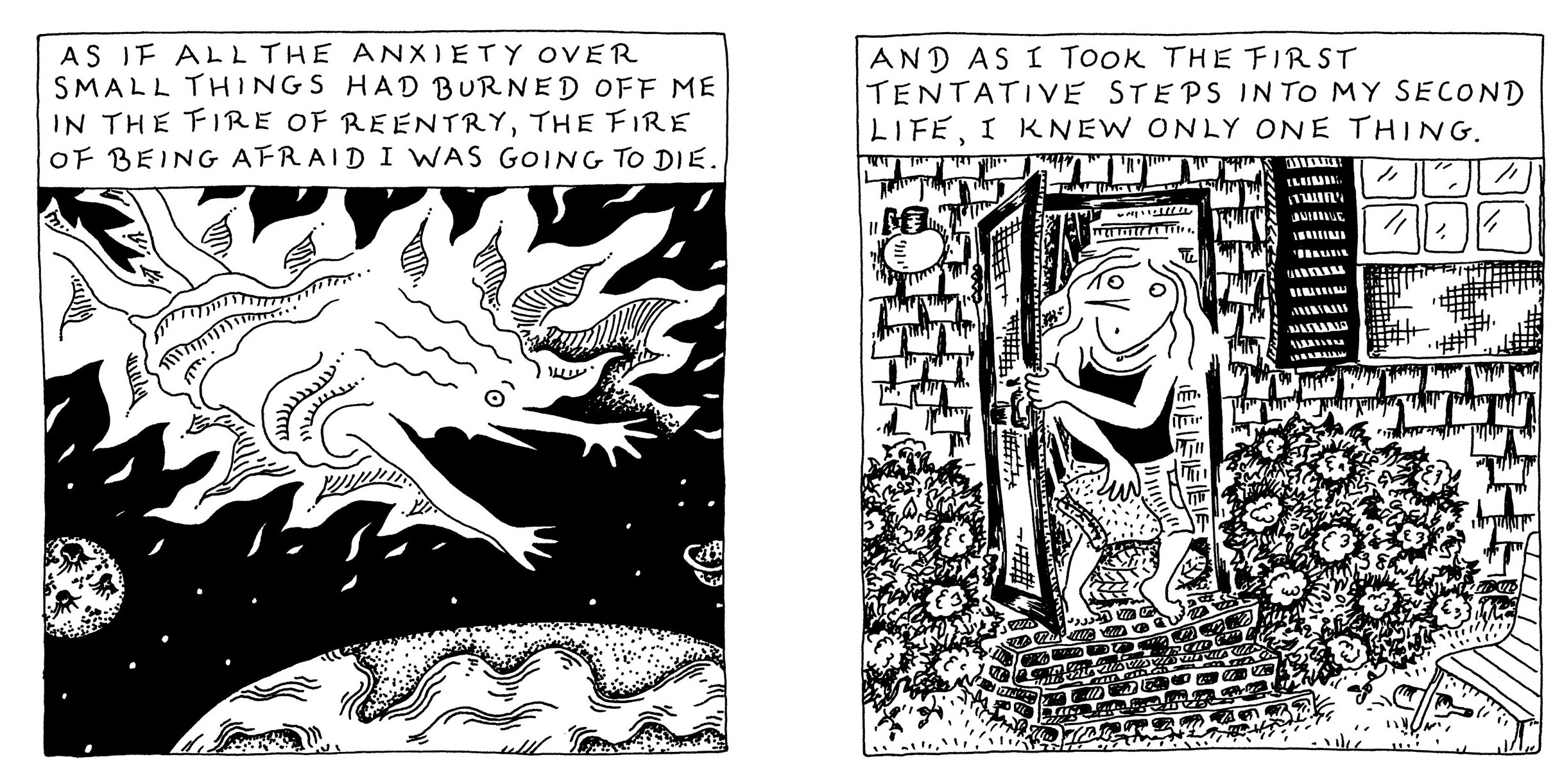

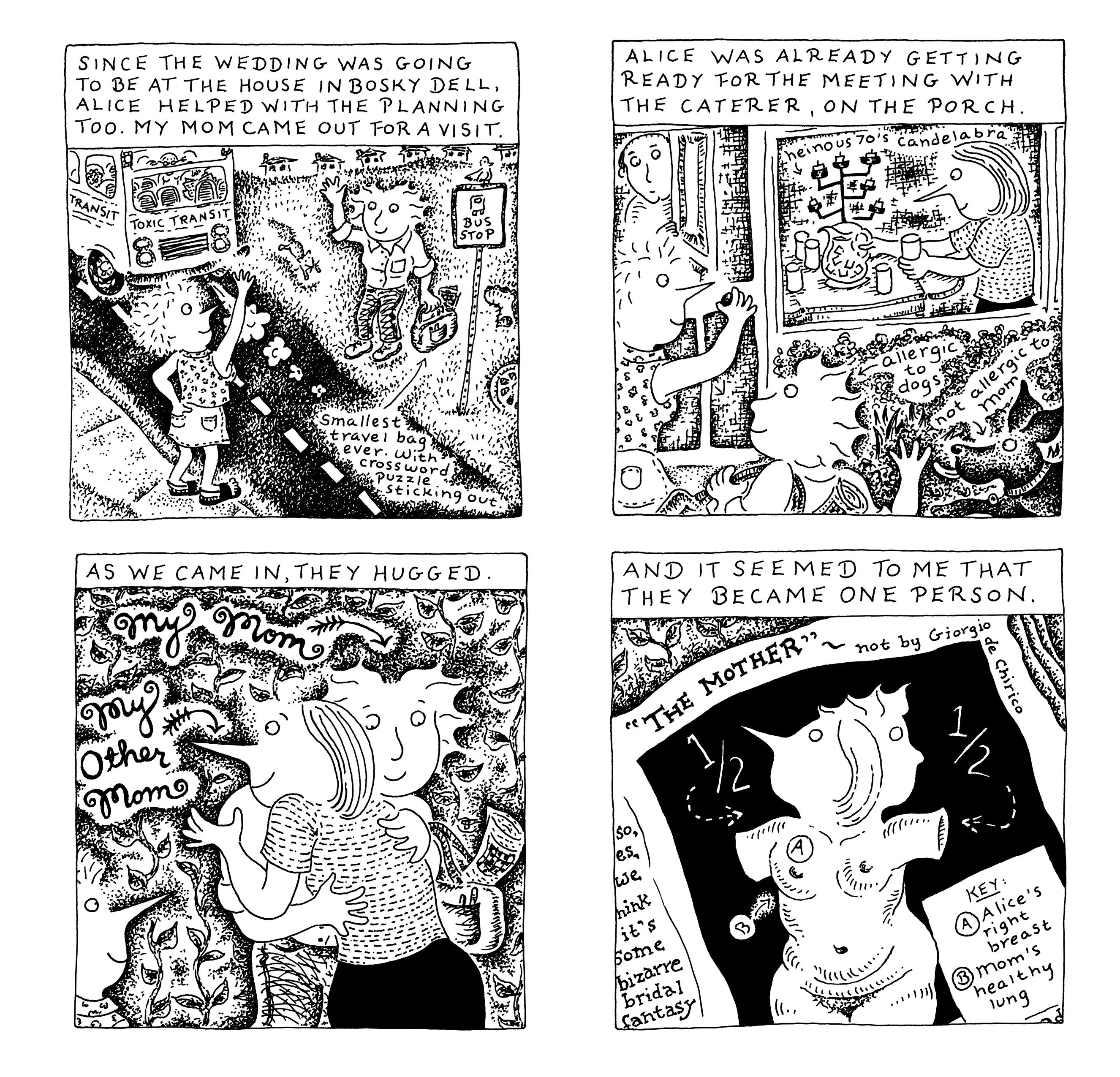

. Hayden's latest graphic novel, The Story of My Tits, chronicles her journey from flat-chested adolescence to adulthood, including her battle with breast cancer at age 43.

How has coming to comix art later in life affected your artistic perspective?

Actually, I came to art early in life. I always drew people and had no interest in painting or color. After illustrating everything at my school and drawing all over everything instead of paying attention in class, I went to college and studied art history instead of art. By not going to art school, I missed the chance to learn about new media, color balance, even encountering other young artists trying comix--but it gave me a great background in the tradition of narrative visual techniques (I loved analyzing how the story was told in each work of art). When I discovered graphic novels, all that knowledge poured back into my work, and nobody cared that I could only draw, only liked drawing people and preferred black-and-white. I'd finally found a medium that was all about gesture, camera view, expression, emotion and how to capture every moment of living breathing life.

Your story could stand alone as a memoir, but the pictures add a layer of emotional poignancy to the narrative. Why did you choose sequential art as the medium for describing your journey?

Your story could stand alone as a memoir, but the pictures add a layer of emotional poignancy to the narrative. Why did you choose sequential art as the medium for describing your journey?

After 15 years of trying to write fiction, I knew I couldn't do this story justice with words. When I use words alone, I lie. The paper is too wide open. Having a single box to fill with limited space for words disciplines me, and my art tends to tell the truth. I found that a graphic novel enabled me to amplify all the aspects of this story--comedy, tragedy, minor details, larger metaphors--to make a more lifelike soup than I could with words.

There are echoes of Judy Blume's Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret and Paula Danziger's The Cat Ate My Gymsuit, which look at adolescence with similar humor and pathos, in your story. Did these types of young adult novels have an influence on your own story?

Young adult novels are not something I'm familiar with, but I have read plenty of humorous essays and autobiography--Ian Frazier, David Sedaris, Colin Nissan--and I've enjoyed the recent flood of female comedy narratives by Tina Fey, Miranda Hart, Caitlin Moran, Lena Dunham and Lizz Winstead--all of which helped me get past my desire to be the next Charles Dickens and take a lighter, less traditional approach to combining humor with just about everything.

This book is really a tale of two "tits": the "tit" mirroring the evolution of your personal growth from youth to adulthood, and then the underlying role that "tit" plays in your mother's and your own cancer diagnosis. What prompted you to juxtapose these two images in this way?

This book is really a tale of two "tits": the "tit" mirroring the evolution of your personal growth from youth to adulthood, and then the underlying role that "tit" plays in your mother's and your own cancer diagnosis. What prompted you to juxtapose these two images in this way?

When I sat down to write a book about my breast cancer, I thought: well, you can't just tell the breast cancer story; you have to begin at the beginning. And where was the beginning? When I was born. And really, that's the set-up for the punchline: that I didn't have tits for a woefully long stretch as an adolescent, while growing up in a family that glorified them, only to have them removed before I was done enjoying them. Not so much a punchline as an unhappy ending, but I liked mixing it up. I also wanted to be sure this was not a victim story but a survivor story--as in, here's the life of a woman, one chapter of which involved this sh**ty breast cancer experience, which she was lucky enough to outrun. And I wanted to set it up so that the moment of my diagnosis hits the reader as hard as it hit me--with all the tangents, ironic, sad, funny, spooky--leading out of it into my past. I didn't want to have to make those connections for the reader. I wanted the reader to go: oh, yeah, look at that, right, right. That's the fun of being the reader.

"The Goddess" plays an integral role in how you deal with difficult situations. When did you come upon this universal symbol of feminism, and which particular goddesses have inspired you most?

The Goddess was a symbol on a pendant I'd picked up from a bead store. I'd recognized the image from art history as a Neolithic "fertility goddess" figurine. I became close to her during the time I went through my breast cancer and I have pretty much dedicated the rest of my life to her. I have met more goddesses along the way, and while studying yoga I was encouraged to think of them all as the same spirit with many different outward manifestations. Saraswati supports my playing music-singing-writing-drawing self; Willendorf stands guard over my middle-aged identity; and my Native American totem--grandmother turtle--reminds me to slow down and remain connected with the earth.

The quote "When we give our energy to others, it must be a conscious act... we give what is right for balance" encapsulates the dilemmas women face in meeting the demands of family and career. How long did it take for you to be conscious of this need for balance? And what steps have you taken to achieve it?

The quote "When we give our energy to others, it must be a conscious act... we give what is right for balance" encapsulates the dilemmas women face in meeting the demands of family and career. How long did it take for you to be conscious of this need for balance? And what steps have you taken to achieve it?

That was some great advice from a therapist I saw during the time I had breast cancer, and I learned more about it in the course of discovering yoga afterward. I truly believe that the year before my diagnosis was the worst imbalance in my life: doing too much for my family and for my community. I was not cut out for it. I bonded with my father early, and I have spent much of life thinking of myself as a man--as a male artist. The family I grew up in got used to my lack of interest in domestic life. My sister filled the nurturing role. When I became a mother, it got more complicated. After breast cancer, I really asked myself: What is my life going to be filled with? And I returned to the joys of my teenage years--drawing, writing, playing the fiddle, and now I'm taking voice lessons as well (I perform with a couple of local bands). I take care of my body with yoga and walking, and I read a lot, which is a great stress-reducer. I give my loved ones what I believe they need, and I do not beat myself up for being the kind of mother and daughter and friend I am. Matisse wouldn't have done that. Why should I?

How difficult was it for you to embrace the different stages of your body through youth, motherhood and middle age and then express this emotional journey graphically? What advice would you give to your own daughter?

How difficult was it for you to embrace the different stages of your body through youth, motherhood and middle age and then express this emotional journey graphically? What advice would you give to your own daughter?

I have bad body-image days just like everyone else. I talk to my daughter about it all the time--we complain about ourselves, then p*** off at society for making us feel that way, then insist that we'll never let ourselves feel crappy again. It's a cycle, like reincarnation. Each time you learn a little more. It wasn't at all difficult for me to express it graphically, because it's so central to the female experience--and to the mastectomy experience. But my daughter gives me better advice than I give her about this. Her generation is really pulling women out of this body image quagmire--it's lovely to watch them go!

Will your work continue focusing on themes of motherhood and your inner "Goddess" or do you have other subjects planned for the future?

I don't know. I continue to be a mother and grateful to my inner and outer "Goddesses," but in my mid-50s, I am entering this fantastic time when I feel I am becoming a third sex, one that includes both of the other two. I can simply be human, more human than I have ever been because I understand so much more of the landscape at this age. It is possible I will move, bit by bit, away from autobiographical to fictional subjects. I'd like to publish a diary project I've been working on for a few years next. I have another collection I'd like to do of poetic short-form comics, and then I have a shoebox of ideas for my next graphic novel. I really look forward to opening that box. --Nancy Powell

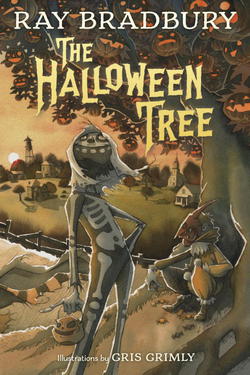

Rejoice, Halloween people! There's a 2015 edition of Ray Bradbury's 1972 classic The Halloween Tree (Knopf), one of the very best Halloween books ever written for eight-year-olds or adults, newly illustrated by the much-admired Gris Grimly. Gather the kids around on an October night and read (out loud, if possible) the deliciously lyrical, globe-circling, time-traveling tale of Mr. Moundshroud and eight trick-or-treating boys in search of their missing, maybe stolen friend Pipkin... "And all the deep dark wild long history of Halloween waiting to swallow us whole!"

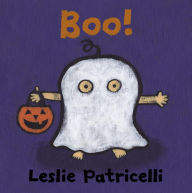

Rejoice, Halloween people! There's a 2015 edition of Ray Bradbury's 1972 classic The Halloween Tree (Knopf), one of the very best Halloween books ever written for eight-year-olds or adults, newly illustrated by the much-admired Gris Grimly. Gather the kids around on an October night and read (out loud, if possible) the deliciously lyrical, globe-circling, time-traveling tale of Mr. Moundshroud and eight trick-or-treating boys in search of their missing, maybe stolen friend Pipkin... "And all the deep dark wild long history of Halloween waiting to swallow us whole!" It's easy to creep out toddlers, so Leslie Patricelli gently eases them into Halloween with the endearing board book Boo! (Candlewick). Here, a tiny trick-or-treating ghost gradually works up to ringing the doorbell solo. As it should be, the pressing questions of the day are "How should we carve our jack-o'-lantern?" and "What should I be?"

It's easy to creep out toddlers, so Leslie Patricelli gently eases them into Halloween with the endearing board book Boo! (Candlewick). Here, a tiny trick-or-treating ghost gradually works up to ringing the doorbell solo. As it should be, the pressing questions of the day are "How should we carve our jack-o'-lantern?" and "What should I be?"

Your story could stand alone as a memoir, but the pictures add a layer of emotional poignancy to the narrative. Why did you choose sequential art as the medium for describing your journey?

Your story could stand alone as a memoir, but the pictures add a layer of emotional poignancy to the narrative. Why did you choose sequential art as the medium for describing your journey?  This book is really a tale of two "tits": the "tit" mirroring the evolution of your personal growth from youth to adulthood, and then the underlying role that "tit" plays in your mother's and your own cancer diagnosis. What prompted you to juxtapose these two images in this way?

This book is really a tale of two "tits": the "tit" mirroring the evolution of your personal growth from youth to adulthood, and then the underlying role that "tit" plays in your mother's and your own cancer diagnosis. What prompted you to juxtapose these two images in this way?  The quote "When we give our energy to others, it must be a conscious act... we give what is right for balance" encapsulates the dilemmas women face in meeting the demands of family and career. How long did it take for you to be conscious of this need for balance? And what steps have you taken to achieve it?

The quote "When we give our energy to others, it must be a conscious act... we give what is right for balance" encapsulates the dilemmas women face in meeting the demands of family and career. How long did it take for you to be conscious of this need for balance? And what steps have you taken to achieve it? How difficult was it for you to embrace the different stages of your body through youth, motherhood and middle age and then express this emotional journey graphically? What advice would you give to your own daughter?

How difficult was it for you to embrace the different stages of your body through youth, motherhood and middle age and then express this emotional journey graphically? What advice would you give to your own daughter?