Svetlana Alexievich, who has spent 30 years exploring human conflict and its aftermath, is the first journalist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Through interviews with thousands of people, from Chernobyl to Kabul, she presents harrowing facts by letting her sources speak for themselves in dramatic monologues. The Swedish Academy cited her work as a "monument to suffering and courage in our time."

Each of her six books has taken three to four years to complete, with 500 to 700 people interviewed per book. Alexievich has perfected a genre that is neither fiction nor nonfiction; she calls it the "collective novel" (she also calls it the novel-oratorio, the novel-evidence, and the epic chorus), created out of interviewing people who have survived some national trauma, asking the right questions, removing the unnecessary repetitions of real dialogue, boiling down their answers to the essence, and arranging these stark reductions in a mosaic-like composition that conveys the full emotional gamut of the historical experience.

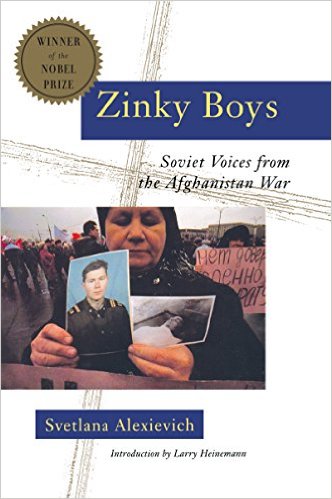

Her first book immediately brought her to prominence--an investigation into the role of women in World War 11 translated as War's Unwomanly Face. Her second, The Last Witnesses, probed the childhood memories of war survivors who were ages 7-12. But her third book, about the Afghanistan War, provoked such violent responses that they became incorporated into the book itself: Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, translated by Julia and Robin Whitby (Norton, $18.95 paperback).

Zinky boys were the dead teenagers sent home from Afghanistan in sealed zinc coffins. Alexievich interviewed survivors of all kinds, amputees and those who lost more than limbs in the war that broke the faith of Russians in their country. Her book about the military disaster that consumed a generation records the testimonies of infantrymen and paratroopers, sergeants and civilians, medics and mothers, nurses and interpreters, widows and engineers, and lets them tell their truths--betrayed by the government, deceived by the press, tricked into volunteering to "go to the aid of the Afghan people."

Zinky boys were the dead teenagers sent home from Afghanistan in sealed zinc coffins. Alexievich interviewed survivors of all kinds, amputees and those who lost more than limbs in the war that broke the faith of Russians in their country. Her book about the military disaster that consumed a generation records the testimonies of infantrymen and paratroopers, sergeants and civilians, medics and mothers, nurses and interpreters, widows and engineers, and lets them tell their truths--betrayed by the government, deceived by the press, tricked into volunteering to "go to the aid of the Afghan people."

Beginning with snatches from her own diary, Alexievich arranges her monologues in three groups she calls "Days," each beginning with an Author receiving a phone call from a furious, anonymous war vet she calls her Leading Character, who condemns what she is trying to do. "What's the point of this book of yours?" he objects. "What good will it do?.... You'll never be able to tell it like it really was over there."

Alexievich then takes the reader through a selection of accounts so full of grief and horror and pain that only the most restrained, even-handed reporting makes them endurable. Vets recount both sides of the Afghan horror, from kicking villagers to death to soldiers being killed with village pitchforks. The book's postscript concludes with a sampling from the storm of hate letters and phone calls provoked by the publication of excerpts from the book.

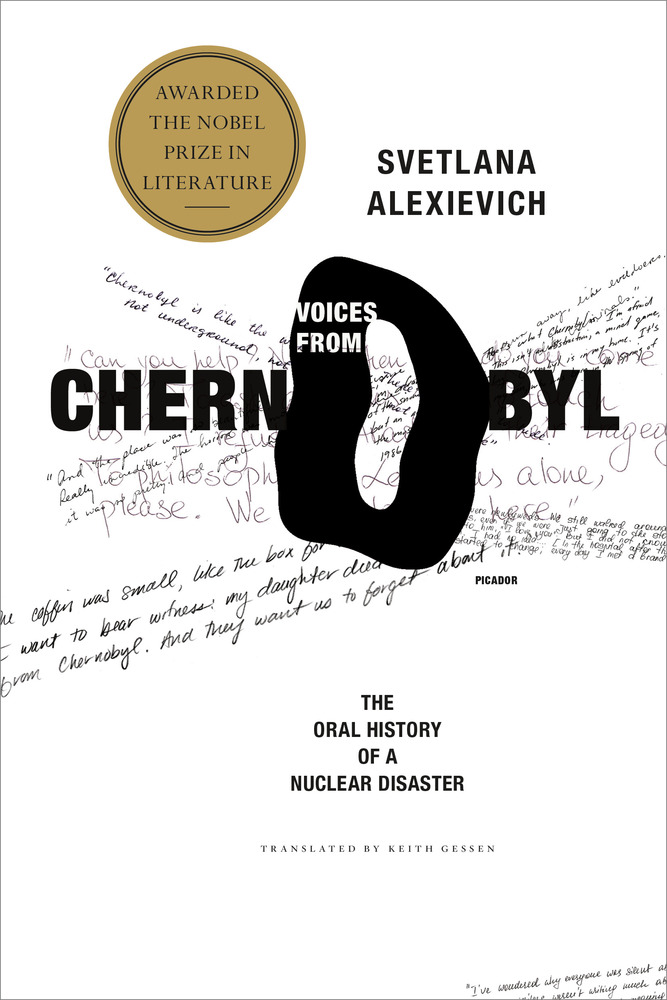

In the same manner, her fourth book--Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, translated by Keith Gessen (Picador, $16 paperback)--covers the 1986 fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the largest technological disaster of the century, 10 times as radioactive as the explosion at Hiroshima. Alexievich doesn't hesitate to show that the nightmare was compounded by incompetence, indifference and out-and-out lies, with 4,000 deaths directly attributable to the accident, while "the number of people with cancer, mental retardation, neurological disorders and genetic mutations increases with each year."

In the same manner, her fourth book--Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, translated by Keith Gessen (Picador, $16 paperback)--covers the 1986 fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the largest technological disaster of the century, 10 times as radioactive as the explosion at Hiroshima. Alexievich doesn't hesitate to show that the nightmare was compounded by incompetence, indifference and out-and-out lies, with 4,000 deaths directly attributable to the accident, while "the number of people with cancer, mental retardation, neurological disorders and genetic mutations increases with each year."

The heartbreaking opening monologue by a fireman's wife is like a tragic short story. Three movements of voices follow. A woman who refuses to leave her home in the evacuation, a man who defies the police to go back for a door that's a family heirloom, a soldier who unwittingly gives his contaminated cap to his son--each contribute their gram of horror to the mix, barely leavened by the alcoholic cab driver braving the radioactive zone to rescue kindergarteners. The book reads like science fiction, survival tales from a poisoned planet where the milk will no longer make cheese and chickens grow black coxcombs and the gardens have turned white with radiation, where families of contaminated farmers are forced to abandon their unharvested fields. With the resulting suicides and abortions, it's a contamination not just of their land and their bodies, but also of their faith in the government.

Alexievich does far more than simply interview. She selects and arranges, she juxtaposes opposites, she records all sides, creating a series of no-nonsense prose poems out of the darkest, saddest realities. From patriotic self-sacrifice to disillusioned questioning, her voices are the products of a culture trained to honor blind faith in the homeland. Zinky Boys and Voices from Chernobyl are her two most readily available--and devastating--books in translation, and others are coming: Random House will publish Second-Hand Time, about the collapse of the U.S.S.R., in summer 2016; in 2017, RH will bring out War's Unwomanly Face, Alexievich's first book, composed of the words of women who took part in World War II, and Last Witnesses, describing that war from the perspective of children. To offset her preoccupation with the tragic nature of life, Alexievich is currently completing a book about love and the pursuit of happiness called The Wonderful Deer of the Eternal Hunt.

Her most unbearable sequences--the descriptions of teenage soldiers in Afghanistan having their limbs blown off or the heartbreaking slaughter of Chernobyl household pets--are minimal and mercifully brief. But they're like bullets. They hurt. These collective novels are not for everyone. Their urgent clarity and unflinching reportage on the far, dark frontiers of the human soul are thoroughly upsetting but never lurid or sensational, always with a humanitarian awareness of the value of life behind her objective portraits of 20th-century horror. --Nick DiMartino, Nick's Picks, University Book Store, Seattle, Wash.

The Collective Novels of Svetlana Alexievich

Zinky boys were the dead teenagers sent home from Afghanistan in sealed zinc coffins. Alexievich interviewed survivors of all kinds, amputees and those who lost more than limbs in the war that broke the faith of Russians in their country. Her book about the military disaster that consumed a generation records the testimonies of infantrymen and paratroopers, sergeants and civilians, medics and mothers, nurses and interpreters, widows and engineers, and lets them tell their truths--betrayed by the government, deceived by the press, tricked into volunteering to "go to the aid of the Afghan people."

Zinky boys were the dead teenagers sent home from Afghanistan in sealed zinc coffins. Alexievich interviewed survivors of all kinds, amputees and those who lost more than limbs in the war that broke the faith of Russians in their country. Her book about the military disaster that consumed a generation records the testimonies of infantrymen and paratroopers, sergeants and civilians, medics and mothers, nurses and interpreters, widows and engineers, and lets them tell their truths--betrayed by the government, deceived by the press, tricked into volunteering to "go to the aid of the Afghan people." In the same manner, her fourth book--Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, translated by Keith Gessen (Picador, $16 paperback)--covers the 1986 fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the largest technological disaster of the century, 10 times as radioactive as the explosion at Hiroshima. Alexievich doesn't hesitate to show that the nightmare was compounded by incompetence, indifference and out-and-out lies, with 4,000 deaths directly attributable to the accident, while "the number of people with cancer, mental retardation, neurological disorders and genetic mutations increases with each year."

In the same manner, her fourth book--Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, translated by Keith Gessen (Picador, $16 paperback)--covers the 1986 fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the largest technological disaster of the century, 10 times as radioactive as the explosion at Hiroshima. Alexievich doesn't hesitate to show that the nightmare was compounded by incompetence, indifference and out-and-out lies, with 4,000 deaths directly attributable to the accident, while "the number of people with cancer, mental retardation, neurological disorders and genetic mutations increases with each year." Stoner languished in obscurity until John Doyle, of Crawford Doyle Booksellers in New York City, recommended the novel to a New York Review of Books editor. NYRB Classics republished Stoner in 2006. Since then, Williams's once-forgotten novel has achieved astounding success. Critics have hailed it as a rediscovered treasure and lost masterpiece. Bret Easton Ellis said Stoner is "one of the great unheralded 20th-century American novels." Ian McEwan called it "a beautiful, sad, utterly convincing account of an entire life."

Stoner languished in obscurity until John Doyle, of Crawford Doyle Booksellers in New York City, recommended the novel to a New York Review of Books editor. NYRB Classics republished Stoner in 2006. Since then, Williams's once-forgotten novel has achieved astounding success. Critics have hailed it as a rediscovered treasure and lost masterpiece. Bret Easton Ellis said Stoner is "one of the great unheralded 20th-century American novels." Ian McEwan called it "a beautiful, sad, utterly convincing account of an entire life."