|

| photo: Sam Zalutsky |

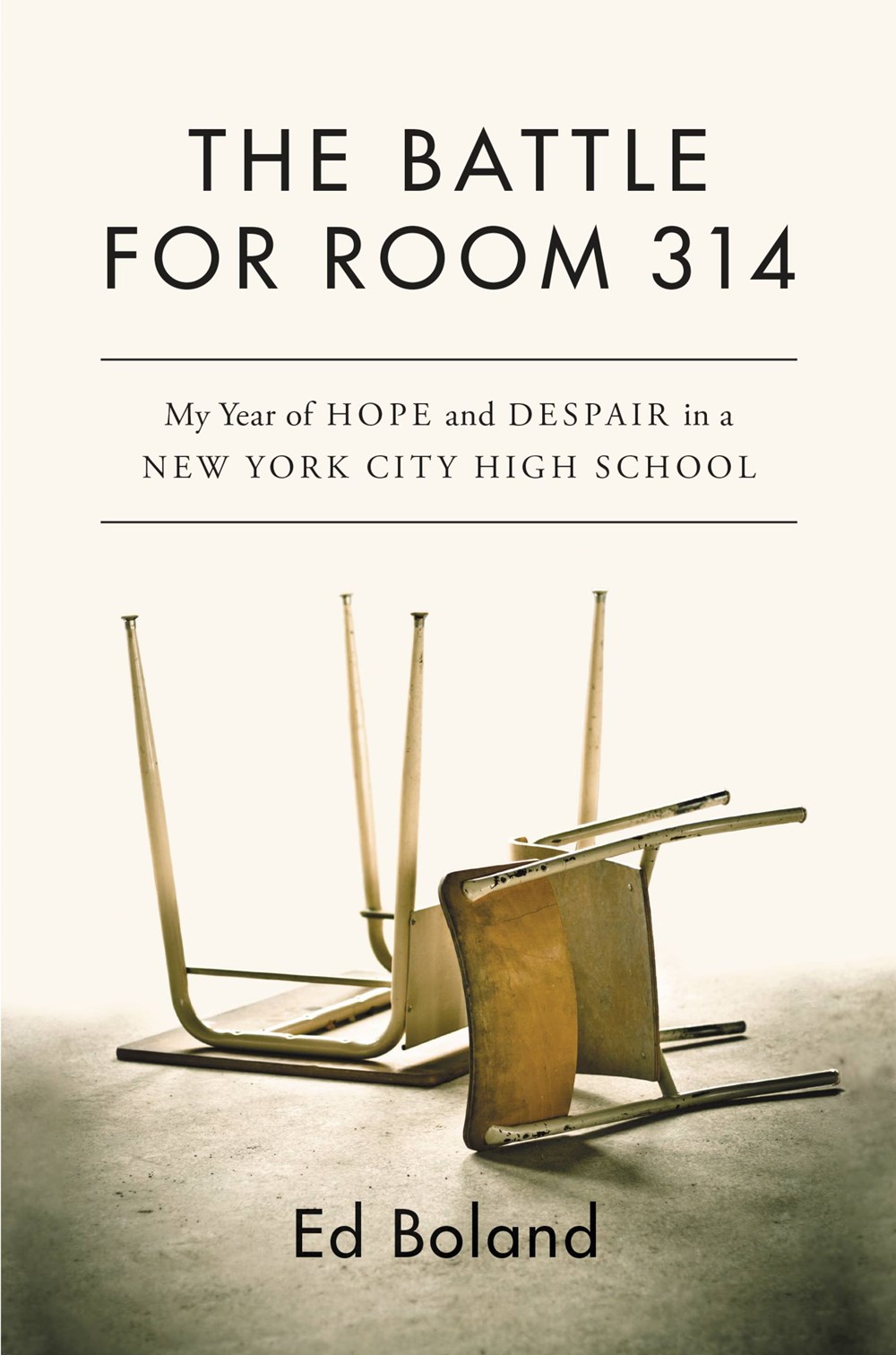

Ed Boland has dedicated his professional life to nonprofit causes, predominantly educational institutions, as a fundraiser and communications expert. Boland was an admissions officer at his alma mater, Fordham University, and later at Yale, and lived in China as a Princeton in Asia Fellow. He resides in New York with his husband. The Battle for Room 314 (see our review below) is his first book and tells the story of his eye-opening year of teaching in a New York City high school.

What was your teaching experience before you decided to do this?

I had taught swimming to little kids, I taught art history to senior citizens, I taught in China and I taught in the program where I work now; I had been a TA in its middle school history section. So I thought I knew vaguely what I was going to get into. I knew it would be tougher, but I had no idea what was waiting for me.

So you weren't going in totally naïve.

No. I worked with kids and worked in schools and worked in higher education and international education, and also went to the trouble of getting the degree in advance. Some people say, "Were you embedded in that classroom, was this a journalism project from the get-go?" No, I really thought I was going to do this.

Do you think you'd still be teaching if you'd started at a different school?

That's an excellent question. I think there was a decent chance, but in some ways I'm glad I saw a more realistic and dire situation because honestly I think I am not a master teacher, I wasn't even a good teacher, but I'm a storyteller. And hopefully I will have far more effect on the education debate by telling the stories of the children I taught.

It seems like a lot of your students didn't view education as a path to a better life. Why do you think that is?

It seems like a lot of your students didn't view education as a path to a better life. Why do you think that is?

I think so much of it has to do with family mindset and the extent of poverty. I think that families that have been in long-term multigenerational poverty, long-term unemployment, public housing, haven't seen people in their communities getting degrees, going to work. They are really disaffected from the broader system. They don't feel vested, because they're not; the system doesn't allow them to be vested. And I think that the kids pick up on that very early. "Someone in my house or I am about to be evicted, incarcerated, stopped and frisked, about to beaten down. How are polynomials really going to help me?"

And what does a teacher say to that?

The good answer is that we all need to broaden the debate. We are so fixated on the schools and the teachers as the answers. And that's not fair. These are social problems not of the schools' making that schools are poorly equipped to solve. And yet we ask them to deal with the brunt of all these problems every day. And the solutions we offer are charter schools, holding teachers to higher standards, Common Core, all these classroom- and school-based solutions. The real solutions are outside of those systems. They have to do with how we fund schools and the fact that we've created this apartheid school system: bad schools for brown kids and good schools for white kids, by and large. Our schools are more segregated now than at any time since 1968. We need to broaden the debate: segregation is the real enemy, poverty is the real enemy. And that's not an easy solution, but in my view, it is the solution. It's not lazy teachers, it's not lousy curriculum, it's poverty that is the culprit.

You offer a lot of good suggestions for how to improve the public schools. It seems many of them would require more funding when we've been seeing a lot of cuts.

I would offer this though: there's a lot that we could do that would not cost us a dime. If you look at immigration reform, if you look at a movement to end mass incarceration for non-violent crimes, if you look at instituting a living wage--none of those are going to raise taxes at all. There were parents who wouldn't come to school meetings because they were afraid of being deported or of interacting with the system. You had parents working two and three jobs who couldn't show up or answer your call. So there's a lot we could do that wouldn't even cost us any money. Then imagine if we did start to invest in it instead of in wars and in building prisons.

Do you see any positive trends for the public schools?

While I certainly don't see charter schools as in any way a replacement for the public school system--and "charter schools" is an impossibly broad term because you're talking about for-profit schools, public charter schools, online schools--I think that the not-for-profit networks have shown some real progress in reforming education. They have acted as excellent laboratories in showing results with lower-income kids. But I see them as laboratories, not as replacements. And I wish there were better sharing between public and charter schools. One thing I don't like about charter schools is, if it's really going to be an experiment, one of the underlying logics of an experiment is to have random assignment. And the fact that there are lotteries and applications and all that--the fact that you even have to fill out a postcard to apply to a charter school will automatically preclude the quarter of families who are in the most chaos and are least equipped to navigate their child's educational success. I wish kids were sent to charter schools in the same way they're sent to public schools. And the metadata shows that they're performing at the same level as public schools. That's why you have to figure out who is adding to the debate, who's really adding innovations, and who is just looking to profit or play. "Let's get together and form a school!" Would you do that with a hospital?

What would you most like readers to take away from your book?

I have to say this: the fact that I had a rough year teaching is not the story. The story is that the life circumstances of the kids I taught were so harrowing and that these very smart kids were so hobbled by poverty. We need to understand that. We're so reliant on our Hollywood hero, that myth that we love, that a dedicated teacher walks into a classroom and 90 minutes later everyone is on their way to the American Dream. People need to understand that as comforting as that is, that is not the reality. My version is closer to the reality. We'll never be able to reform the system unless we embrace that and understand it.

And people say, "Oh, you taught for one year. What do you have to say on this subject?" That's a fair question, but what I tell them is: so many teachers steel themselves to the reality around them that they just teach. I was the person who looked at my students and could see only their life circumstances and I couldn't get that out of my head. For a lot of veterans, out of necessity they soldier on, they're inured to the reality. They couldn't tell the story in the same way as someone who is seeing it for the first time. --Sara Catterall

Ed Boland: Hard Reality in the Public Schools

Jennifer L. Holm and her brother Matthew Holm, the team behind Babymouse and Squish, launch their My First Comics series with two board books about feelings: I'm Sunny! and I'm Grumpy (Random House). As the author posted on Nerdy Book Club, "Comics do a great job of teaching the building blocks of reading in a visual way. Children can learn inference by studying the pictures. They learn about dialogue because they can 'see' it in a speech bubble. They learn to navigate left to right on the page. They start to understand human emotions visually."

Jennifer L. Holm and her brother Matthew Holm, the team behind Babymouse and Squish, launch their My First Comics series with two board books about feelings: I'm Sunny! and I'm Grumpy (Random House). As the author posted on Nerdy Book Club, "Comics do a great job of teaching the building blocks of reading in a visual way. Children can learn inference by studying the pictures. They learn about dialogue because they can 'see' it in a speech bubble. They learn to navigate left to right on the page. They start to understand human emotions visually." British author-illustrator Jamie Smart's milk-snortingly funny Bunny vs. Monkey (David Fickling/Scholastic) for ages 7 to 10 is an irreverent, over-the-top comic series debut about an egomaniacal monkey who crashes from space and decides to rule the woods as emperor of Monkey-topia. Add Skunky, a genius inventor who builds the giant Mole-a-Rolla, to the mix and watch the bumbling woodland animals scramble for power.

British author-illustrator Jamie Smart's milk-snortingly funny Bunny vs. Monkey (David Fickling/Scholastic) for ages 7 to 10 is an irreverent, over-the-top comic series debut about an egomaniacal monkey who crashes from space and decides to rule the woods as emperor of Monkey-topia. Add Skunky, a genius inventor who builds the giant Mole-a-Rolla, to the mix and watch the bumbling woodland animals scramble for power.

It seems like a lot of your students didn't view education as a path to a better life. Why do you think that is?

It seems like a lot of your students didn't view education as a path to a better life. Why do you think that is?