|

| photo: Caroline Irby |

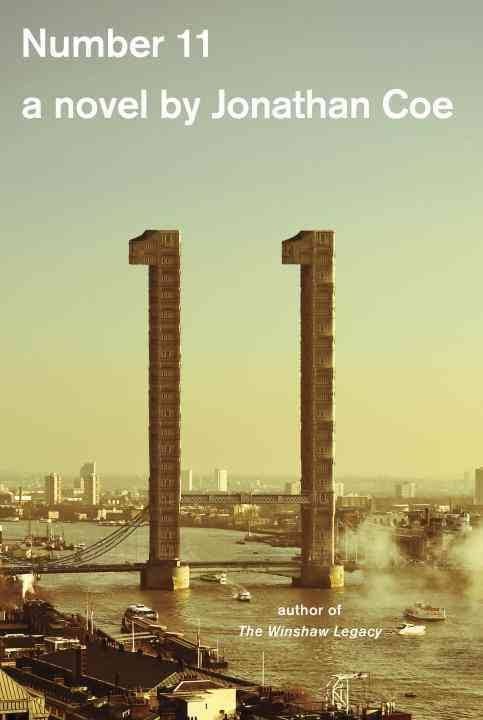

Jonathan Coe is the author of Number 11 and (not coincidentally) 10 previous novels, including The Rotter's Club and The Winshaw Legacy (originally published in the U.K. as What a Carve Up!). Born in a suburb of Birmingham, England, Coe holds degrees from Cambridge and Warwick University, and has been awarded the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, the Samuel Johnson Prize, the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize and France's Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger and Prix Médicis Étranger. Coe is best known as a satirical novelist, and his novels typically feature childhood friendships and family relationships, often within the context of British class issues and politics. Number 11, a (loose) follow-up to The Winshaw Legacy, is told in five separate stories and centers on two friends--Rachel and Alison--as they come of age in an era of growing economic disparity. Coe lives in London with his wife and two daughters.

What books have you enjoyed recently?

I've been enjoying a book by Laline Paull called The Bees. It's a fantasy novel set in a beehive--the characters are bees, but it's also a political novel about power structures. It's almost Orwellian in its political approach.

Is there any book you're a proselytizer for?

I always recommend that readers track down the novels of Rosamund Lehmann. I discovered them when I was a postgrad student in the '80s. I particularly love her debut novel, Dusty Answer, and one of her later novels called The Echoing Grove. These are really very intense, intimate books of the feminine consciousness, and they were a great inspiration for me in the '80s, in terms of helping me to write better from a female perspective.

Why did you write Number 11?

It began in the vaguest possible way: I was signing a two-book deal with my publisher, and I didn't have any idea or any title for the second book. So I just wrote in the proposal "political novel set in contemporary Britain." And as I thought about that phrase over the next few months I thought, well, what have I committed to here?

That's quite a writing prompt you gave yourself.

Yeah. Well, and I did that once in What a Carve Up! back in the '90s. How can I do it in a way that will be fresh and different, but also connected to it somehow? So I was already starting with a dual approach. I wanted there to be connections with What a Carve Up!, but I also wanted this book to be as different from it as possible.

Should readers have first read What a Carve Up!/The Winshaw Legacy?

It shouldn't matter. A few years ago I wrote two interconnected novels [The Rotter's Club and The Closed Circle], and I realized from a very practical point of view then that I put a very severe limitation on the readership of that book.

You know, it's a wonderful writer's fantasy that you have this evolving canon of work, and you have devoted readers who are reading one book after another and keeping them all in their heads. But in fact it doesn't work like that at all.

Do you feel that Brexit represents a fundamental shift in the British psyche, or more of a burp?

Do you feel that Brexit represents a fundamental shift in the British psyche, or more of a burp?

I don't think it's a fundamental shift. But it provided a brief and unexpected opportunity--rather in the way that the recent U.S. election did, but there are differences as well--to give the establishment a good kick in the crotch. Seventeen million people voted for Brexit, and that's a big number. And it's crazy to argue that they did so for the same reason, or the same half a dozen different reasons.

I would say that Number 11 in some ways is an anti-establishment book, because it attacks the right-wing press, it attacks the super-rich, and so on. But post-Brexit, people in Britain are now saying no, that's not what the establishment is. In fact, the establishment is political correctness; it's enforced globalization; it's enforced immigration. Britain's notion of what the establishment consists of has been flipped in the last year. And those of us who thought we were against it are now being told that we're a part of it.

There are clearly issues that you address in Number 11 that Brexit has overshadowed. Which are the most critical?

Rising inequality, and rising job insecurity among the middle classes and the working classes. Real and biting poverty, rising among the least well-off part of the population. Really, you could be following politics in the U.K. for the last seven months and not have thought about anything other than Brexit. Even the worsening National Health Service crisis, which has gotten to the point that the Red Cross is saying that the British hospitals are now in a state of emergency. This would be headline news in every paper and on every British TV station, in any other circumstances. But even that has to make way for the endless Brexit narrative, which is going to be with us for another five or 10 years.

Why do you think satire isn't so popular nowadays?

The paradox of satire to me is that it's only worth doing if it makes its audience rethink their assumptions, and therefore makes them uncomfortable in some way. And you have to reconcile that with the pleasure principle, which is that, whether you're making a TV show or writing a novel like Number 11, you're there to entertain people on one level or another.

The problem these days is that straight realism is the default setting for social commentary. It doesn't always hit hard enough, and there's too much of it. I wanted to stick something in Number 11 that was simple and strong, even a little bit crude and vulgar. A story about a girl who leaves Oxford to become a tutor to the super-rich, well, that could be funny and make a few points, but I thought it would stick in people's minds longer after they finished the book if there were some giant spiders in there as well.

And if newspaper columnists are going to use clichés as stupid as a black one-legged lesbian on benefits--and they do, repeatedly--then that's a kind of gift to a writer like me.

You go after comedians as enablers of complacency. Is that self-deprecation, or is there a distinction between political comedy and what you're doing?

That's an important distinction. Because satire and political comedy are not necessarily the same thing. Satire isn't satire unless it makes the audience uncomfortable. And a lot of political comedy does the opposite of that. And it becomes, to use Michael Frayn's words, a kind of "community hymn-singing," which is very comforting and reassuring, but doesn't take us forward very far.

Another big target of Number 11--the issue for which you reserve the most venom--is income inequality. What's changed for you in the last year?

I've thought about this in the time since the book was published, and really I think the three main themes of the book are fear, nostalgia, and anger. The kind of low-level frustration, anger, envy, sense of injustice and inequality which burns slowly throughout the book kind of erupts in the last two pages. Fear, anger, and nostalgia: F-A-N. Fan fiction.

There's my headline.

See, I'm writing your piece for you. --Zak Nelson, writer and bookseller

Jonathan Coe: Satire as F.A.N. Fiction

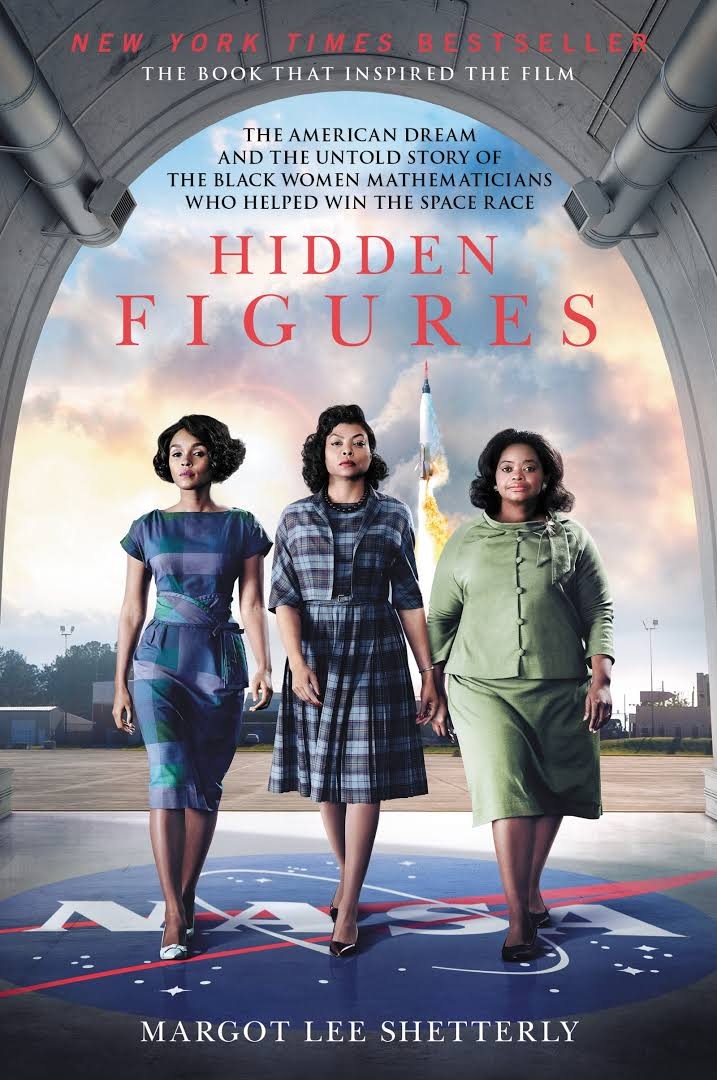

On January 6, the film adaptation of Margot Lee Shetterly's Hidden Figures (Morrow, $15.99) hit box offices with an (ahem) astronomical impact. With superb performances by Taraji P. Henson as Katherine Johnson, Octavia Spencer as Dorothy Vaughan, and Janelle Monáe as Mary Jackson, the true story of African American women whose calculations got John Glenn and other astronauts into space and back down again safely has earned some long overdue recognition. These brilliant mathematicians crunched incredible numbers while facing the cruelties of Jim Crow segregation; without them, the space race would have looked far different.

On January 6, the film adaptation of Margot Lee Shetterly's Hidden Figures (Morrow, $15.99) hit box offices with an (ahem) astronomical impact. With superb performances by Taraji P. Henson as Katherine Johnson, Octavia Spencer as Dorothy Vaughan, and Janelle Monáe as Mary Jackson, the true story of African American women whose calculations got John Glenn and other astronauts into space and back down again safely has earned some long overdue recognition. These brilliant mathematicians crunched incredible numbers while facing the cruelties of Jim Crow segregation; without them, the space race would have looked far different. Bravery in the face of discrimination can also be seen in the black soldiers of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion during World War II. The Wereth 11, as they have come to be called, mastered the 155 mm howitzer for vital fire support during the Battle of the Bulge. However, as Denise George and Robert Child report in The Lost Eleven (NAL, $28), these men were omitted from U.S. casualty lists after they were captured, tortured and executed by German soldiers in December 1944, leaving them nearly forgotten to history.

Bravery in the face of discrimination can also be seen in the black soldiers of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion during World War II. The Wereth 11, as they have come to be called, mastered the 155 mm howitzer for vital fire support during the Battle of the Bulge. However, as Denise George and Robert Child report in The Lost Eleven (NAL, $28), these men were omitted from U.S. casualty lists after they were captured, tortured and executed by German soldiers in December 1944, leaving them nearly forgotten to history. Such disregard for their sacrifice is not only an example of pervasive American racism, but also a flagrant betrayal of the stipulation Frederick Douglass gave for African American enlistment nearly 80 years earlier, during the Civil War: "the same rights and protection guaranteed to them as to other men who fight [U.S.] battles." Our review of Frederick Douglass in Brooklyn (Akashic, $15.95), edited by Theodore Hamm, points out how the orator "presciently touched upon social issues of division and assimilation still relevant in the 21st century."

Such disregard for their sacrifice is not only an example of pervasive American racism, but also a flagrant betrayal of the stipulation Frederick Douglass gave for African American enlistment nearly 80 years earlier, during the Civil War: "the same rights and protection guaranteed to them as to other men who fight [U.S.] battles." Our review of Frederick Douglass in Brooklyn (Akashic, $15.95), edited by Theodore Hamm, points out how the orator "presciently touched upon social issues of division and assimilation still relevant in the 21st century." And readers will surely appreciate music journalist Tony Fletcher's In the Midnight Hour (Oxford, $27.95), a biography of Rock and Roll Hall of Famer "Wicked" Wilson Pickett, "a man who helped put soul music on the map." These represent just a few important figures in history both black and American. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

And readers will surely appreciate music journalist Tony Fletcher's In the Midnight Hour (Oxford, $27.95), a biography of Rock and Roll Hall of Famer "Wicked" Wilson Pickett, "a man who helped put soul music on the map." These represent just a few important figures in history both black and American. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Do you feel that Brexit represents a fundamental shift in the British psyche, or more of a burp?

Do you feel that Brexit represents a fundamental shift in the British psyche, or more of a burp? In 1935, Lewis turned his critical eye to American politics and the rise of fascism in Europe with It Can't Happen Here. The novel imagines populist U.S. Senator Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip elected president on promises of drastic economic reforms and conservative social values. Once in power, Windrip seizes total government control with SS-style paramilitary forces à la Adolf Hitler. Most of the plot follows journalist Doremus Jessup's participation in a dissident revolution. The character Windrip bears an unmistakable resemblance to real-life Louisiana politician Huey Long, a firebrand populist assassinated just after the novel's publication but before his planned 1936 presidential run.

In 1935, Lewis turned his critical eye to American politics and the rise of fascism in Europe with It Can't Happen Here. The novel imagines populist U.S. Senator Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip elected president on promises of drastic economic reforms and conservative social values. Once in power, Windrip seizes total government control with SS-style paramilitary forces à la Adolf Hitler. Most of the plot follows journalist Doremus Jessup's participation in a dissident revolution. The character Windrip bears an unmistakable resemblance to real-life Louisiana politician Huey Long, a firebrand populist assassinated just after the novel's publication but before his planned 1936 presidential run.