|

| photo: Virginia Sherwood |

Chris Hayes is the Emmy Award-winning host of All In with Chris Hayes on MSNBC, the New York Times bestselling author of Twilight of the Elites, and an editor-at-large at the Nation. His newest book, A Colony in a Nation, argues that American society has been split into two parts: the Colony and the Nation. In the Colony, life is characterized by aggressive policing and abridged civil rights. The Nation enjoys a much higher quality of life with more lenient policing. Hayes explains how the dynamic was created and why it persists.

How did you come up with the Colony/Nation framework?

Two things led me to it. The first was my time in Ferguson after the controversial police shooting of Michael Brown. I was overwhelmed by the ways in which the police felt so much like an occupying force. It felt that way not just to the protesters and residents, but the media as well. And when you talked to residents, you heard stories of police conduct that sounded like the kind of petty, capricious predation I normally associate with dictatorships or places under occupation, not a liberal democracy. (I should make the obvious point here that this is the experience of policing for millions of black and brown folks all over the country). As I continued to report, I was struck how policing in the U.S. looks nothing like the ideal notion of democratic accountability. Then I read Nixon's 1968 speech, in which he uses this phrase about African Americans: "They don't want to be a colony in a nation." And it stuck in my head. That's basically what we've created.

Would it be fair to say that your book is, in large part, an attempt to explain black and brown experiences of the law to white America?

As a writer, you want everyone to read your book, across every racial and ideological category. In part, this book is trying to explain to white people why the Colony/Nation divide affects everyone, both as a matter of racial justice, but also as a question of the most fundamental democratic commitments we have as a citizenry and people.

But for readers who are already familiar with the effects of this policing regime, particularly readers of color, I hope the book offers some fresh insight into how the system got built. Like, why did white people make this? And using my own experiences to excavate the nature of white fear and how powerful and seductive it is, I hope people come away feeling they have a better sense of the political substrate of the system we've built.

Do you think that citizens of the Nation truly don't understand how bad things are in the Colony or do they understand but consider it a small price to pay for personal safety?

I think it's both. The vast majority of people aren't spending a ton of time thinking about criminology. And at an intuitive level, it's not crazy to think, "well, we had a lot of crime and then we hired a lot more cops and started putting a lot more people in prison and crime went down." But I also do think faith in that basic story is predicated on not having to confront on a daily basis the immense costs that mass incarceration and stop-and-frisk policing impose on our fellow citizens. It's not that different from the ways in which Americans think about American foreign policy--they hear about it in an abstract sense, but they don't have to directly experience the worst consequences of it.

America was founded with different systems of justice already in place in regard to white citizens and black slaves. Hasn't black America always been "a Colony in a Nation?" What has changed?

Of course, from slavery to Jim Crow, separate systems of justice are foundational. And, in fact, this notion of internal colonization and separateness is an old one. I quote DuBois referring to black Americans as constituting a "nation within a nation." What's changed, I think, and what distinguishes this particular era is the development of black political power. Part of the structure of Jim Crow was to block enfranchisement and black representation. Today, there's greater black elected political power than any time in the nation's history (though it is still a small fraction of all elected reps) and yet that enfranchisement has not eradicated this internal division and the democratic deficiency it represents.

President Trump successfully ran as a "law and order" candidate despite crime rates at historic lows. What is fueling the disparity between perception and reality that Trump capitalized on? Do you worry that the Colony will suffer more under his administration?

Well, yes. I mean, he basically just threatened to declare martial law in Chicago because he was watching a Fox News segment on violence there. Remember, Donald Trump is someone whose entire worldview was shaped in the high crime New York City I grew up in, which I describe in the book--one where white fear thrived. Trump famously called for the execution of the Central Park Five, who spent years in prison before being exonerated. He's never apologized and still contends they were guilty! In many ways Trump was able to the take the local politics of law and order and the cultivation of white fear of the New York City of my youth and project it out across the nation, integrating other threats--Muslims and immigrants primarily. The message is that the country is disordered and dangerous due to lawlessness at the border: unruly, violent criminal immigrants, a Muslim fifth column and inner-city black violence. In the book, I call this "the political equivalent of enriched uranium." It's a way of triggering the absolute worst impulses in white voters, and as a campaign tactic it's been very successful. We're just beginning to see--with the immigration executive order that bans travelers from seven Muslim countries--how it works as a governing agenda.

America is a nation founded on revolution but obsessed with order. How do you think veneration for our rebellious ancestors coexists in American minds with such a strong intolerance toward disunity of any kind?

This is a great question and touches on a great historical irony I wrestle with at length in the book. The same folks who attended tea party rallies with Gadsden flags and tricorne hats are the most likely to say police aren't sufficiently respected and that you should just do what a cop says, no matter what. There's a deep tension there! The original tricorne hat crew used to like to beat up customs officers and tar and feather them. Can you imagine, if a mob did that to a modern-day police officer, how constitutional conservatives would feel? So, I don't think there's a single answer. The tension between fidelity toward our revolutionary founders and our deep desire for order is forever unresolved and plays out in all kinds of ways in our politics.

Books of this kind often identify a problem and then propose solutions. I didn't find much in the way of policy prescriptions in A Colony in a Nation. Was that a deliberate choice?

It was absolutely intentional. I wanted to avoid what some people call "The Last Chapter Problem." It's what happens when a nonfiction author lays out a critique of some social problem in the first 90% of the book and then uses the last 10% to attempt to solve it. It rarely works. In fact, I did precisely this in my first book, Twilight of the Elites. The first 90% of that book holds up, I think, remarkably well. In fact, I think in many ways it's more relevant than it's ever been. But I can't say the same for the last chapter. I also think I was inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates, who believes that it's not a social critic's job to offer solutions. If people are moved by the book, they will seek out experts and advocates offering concrete solutions.

Is there a "win-win" scenario or does any potential fix require there be a "loser?"

That's the big question, isn't it? I want to believe it's win-win. I mean, I genuinely do believe we can have a more equal, safer nation, where people can flourish and exercise the full liberty and autonomy that should be our birthright as Americans. But I also don't want to discount the more difficult notion that the current arrangement represents a kind of redistribution from the Colony to the Nation and that abolishing the "colonial" arrangement would mean that the Nation would lose privileges and benefits it currently enjoys. We need to develop a political language and framework to destroy the boundaries of the Colony and the Nation even if that's true. --Hank Stephenson

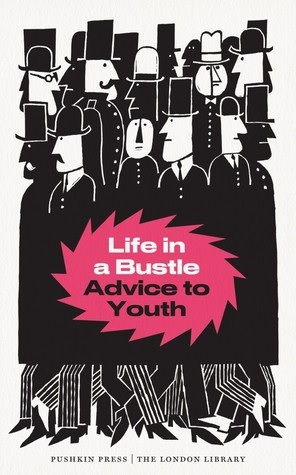

Age-old wisdom can easily become lost amid today's growing mountains of competing ideologies. In his 1915 address to students of the Froebel Educational Institute, Jewish scholar C.G. Montefiore stressed the importance of balancing an open, curious mind with one ready to test new fads and theories for durability--a pivotal habit for those who wish to stay young while growing old. Pushkin Press' London Library series gives readers a chance to dip into knowledge from a century ago, and I'd say Life in a Bustle: Advice to Youth (which contains Montefiore's speech and two other turn-of-the-century pamphlets on health and well-being in a busy society) holds up superbly.

Age-old wisdom can easily become lost amid today's growing mountains of competing ideologies. In his 1915 address to students of the Froebel Educational Institute, Jewish scholar C.G. Montefiore stressed the importance of balancing an open, curious mind with one ready to test new fads and theories for durability--a pivotal habit for those who wish to stay young while growing old. Pushkin Press' London Library series gives readers a chance to dip into knowledge from a century ago, and I'd say Life in a Bustle: Advice to Youth (which contains Montefiore's speech and two other turn-of-the-century pamphlets on health and well-being in a busy society) holds up superbly. I'd only add that stopping a moment to marvel at the non-human wonders that surround us, too, can bring a youthful jolt back into the day. Bloomsbury's Object Lessons series dwells on subjects many of us may take for granted: eggs, traffic, trees, earth. In the hands of contributing essayists like Nicole Walker, Paul Josephson, Matthew Battles, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Linda T. Elkins-Tanton, however, such commonalities leap from the doldrums with a rush of color.

I'd only add that stopping a moment to marvel at the non-human wonders that surround us, too, can bring a youthful jolt back into the day. Bloomsbury's Object Lessons series dwells on subjects many of us may take for granted: eggs, traffic, trees, earth. In the hands of contributing essayists like Nicole Walker, Paul Josephson, Matthew Battles, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Linda T. Elkins-Tanton, however, such commonalities leap from the doldrums with a rush of color.