|

| photo: John Pagliuca |

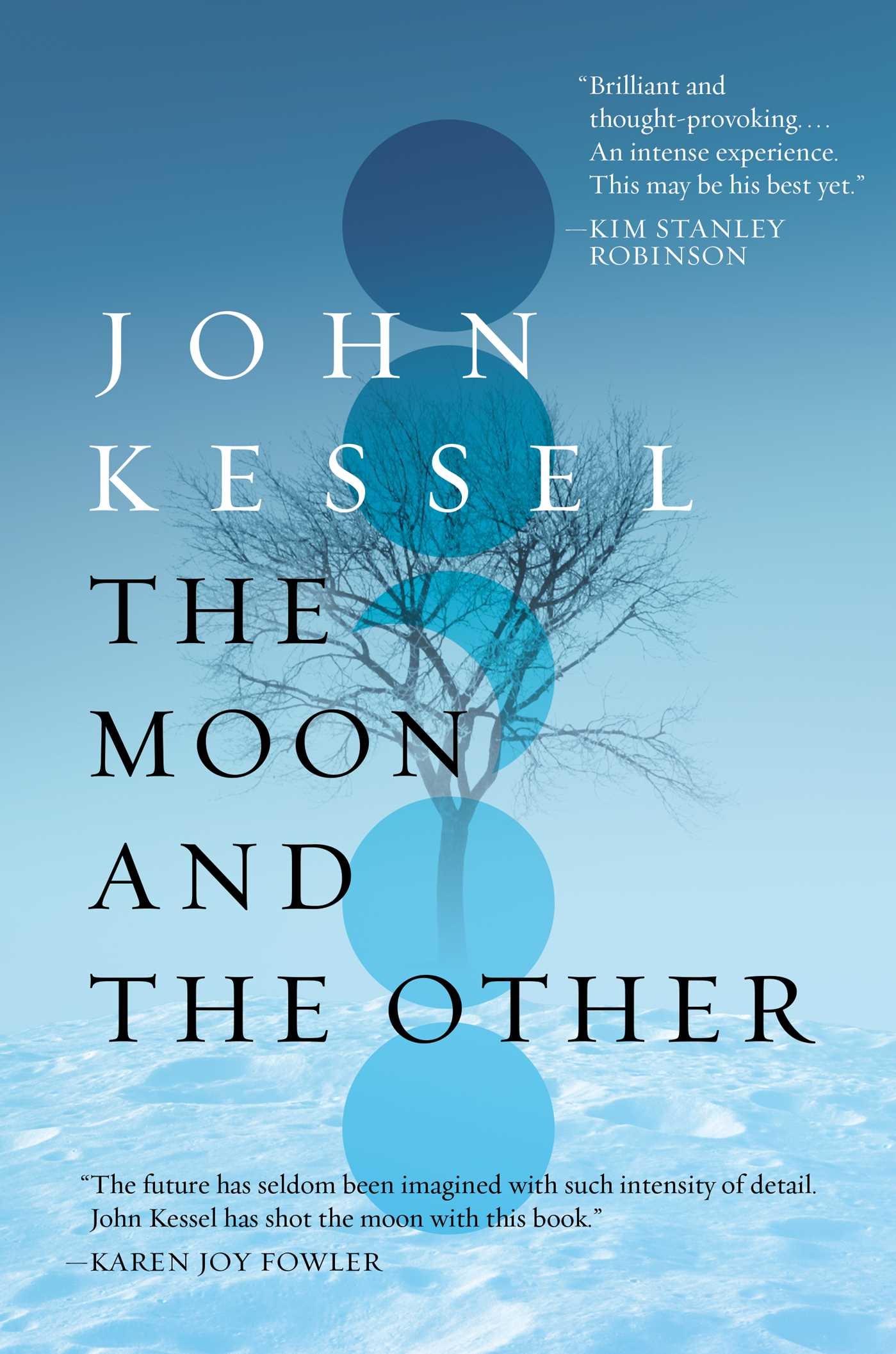

John Kessel is the author of the novels Good News from Outer Space and Corrupting Dr. Nice and the story collections Meeting in Infinity, The Pure Product and The Baum Plan for Financial Independence and Other Stories. His fiction has received the Nebula Award, the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award and the James Tiptree Jr. Award for fiction dealing with gender issues. He teaches American literature and fiction writing at North Carolina State University. He lives in Raleigh with his wife, the novelist Therese Anne Fowler. Kessel's new novel, The Moon and the Other (reviewed below), recently published by Saga Press, is set on the moon in the 22nd century and tells two love stories, in two politically opposed lunar colonies--the patriarchal Persepolis and the matriarchal Society of Cousins.

What was the genesis of The Moon and the Other?

When my daughter was little, I'd take her to daycare and watch her on the playground with other kids. There was a difference in the way that the girls and the boys played. The boys would run around, often doing solitary things. The girls would sit in a sandbox doing things together. So I began to wonder: To what degree is gendered behavior innate, and to what degree is it learned?

I read up about primate behavior, including chimpanzees and bonobos, both related to human beings, but with different cultures. That started me wondering whether there are other ways society could be organized. I didn't see myself as advocating anything, but I did consider how the world might be organized differently.

There's a great scene where the protagonists meet with lawyers for a custody hearing, and they're serving tea and greeting each other with hugs.

Bonobos have a female-dominated culture where they defuse conflict by hugging and kissing and snuggling. And having a lot of sex.

Sex is very open and free and unrestricted in the Society of Cousins. Heterosexual sex, homosexual sex, every variety of sexuality. There are personal choices involved, but the culture doesn't repress sexuality.

And you nod to other genders...

That's right. I'm very aware of the rapid changes in our sense of what makes gender. I don't think gender is a strict binary, and it is somewhat fluid.

In creating the Society of Cousins, did you intend to write about femaleness?

I'd say it's more about masculinity. I feel our culture offers impoverished options for people to be men.

Men are asked to behave in limited ways. I'm not saying men aren't privileged--men are very much privileged in our society--but I also think that the roles offered to them, the ways you're supposed to be male, require cutting parts of your heart out in order to fit in.

How do you define science fiction?

How do you define science fiction?

The writer Frederick Pohl said that science fiction is a way of thinking about things. It's similar to thinking in terms of sociology, or politics, or any number of other disciplines. You suggest alternatives, project consequences, and see how it looks.

The main thing is, you have to put abstract ideas into the lives of individual people. It's not an essay you're writing. We talk about the ideas I was putting into the book, but in the end, I wanted to write a story about some people. I want you to get caught up in the characters' problems, with risk, adventure, even action scenes.

And explosions! You can't have a science fiction book without explosions!

Kim Stanley Robinson blurbed this book, and one of his lesser-known novels, Pacific Edge, has an Ecotopia-like plot that revolves around a zoning battle. So was that an inspiration for the custody battle at the center of this novel?

I am one of Kim Stanley Robinson's biggest fans. I've read pretty much everything he's ever written. In each book, he looks at different aspects of society and makes them into personal stories. Pacific Edge might've been at the back of my mind. I know that I've learned things from reading his work.

There's a lot of science in what's otherwise a character-driven story. Why?

I like science fiction that takes science seriously and tries to be as accurate as possible. It annoys me a great deal when a story just abandons scientific reality for the sake of a plot. I have a degree in physics, so I try very hard to make it as plausible as I can, given the kind of story I'm telling.

I read a lot about the lunar environment and how to create a colony that would be self-sustaining in an incredibly inhospitable place. I mean, you don't have air, you don't have water. You have immense troubles with radiation. Living on the moon, you'd have to solve all these things long-term in order to sustain millions of people.

My most prosperous colony, Persepolis, is located at the lunar south pole. Why? It's one of the coldest spots in the solar system, down to 40 degrees Kelvin, but that's where probes have discovered deposits of ice. Water is a precious commodity, and extremely massive. It would be very expensive to bring water from the earth to the moon. So if there's a place where you can actually mine ice on the moon, that would be a tremendous economic advantage.

How would you mine a place like that, what would be the risk involved, and what would be the economics? That real science gave my colony a tangibility.

There's an optimism to this book. It feels a bit like a golden age science fiction novel. But those came out of an era that was very optimistic.

It's easy for people of my generation, at my age, to get down on the world. The human race does a lot of stupid things, but I feel that we have to try to do better. We're capable of it. I think it's incumbent on writers to imagine things that might be better.

It has a sense of wonder, too.

Science fiction should be fun. I want to show you things you've never seen before. I'm going to show you what it's like to live inside a huge domed crater, and how it works. I'm going to show you an underground forest on the moon, and I'm going to take you to the ice mine where the temperature is near absolute zero, and I'm going to show you an intelligent dog.

I put an ocean and an artificial beach underground on the moon. Could you do it? How? I wanted to create a place where people on the moon who've never seen water beyond what you could put in a cup can go to a beach and actually swim in water.

And I know I'm the only science fiction writer ever to put a lot of thought into how you would manufacture pianos on the moon.

What authors are you a proselytizer for?

I have my favorites, writers of my generation who I'm fond of, like Karen Joy Fowler, James Patrick Kelly, Bruce Sterling and Kij Johnson. There is a generation of new science fiction and fantasy writers that I am not as familiar with as I should be. People like Usman Malik, Lavie Tidhar, Nora Jemisin, Saladin Ahmed, E. Lily Yu, Alyssa Wong, Eugene Fischer, a dozen others.

What are you working on now?

I just turned in a draft of a new novel called Pride and Prometheus. It was originally a story I wrote in 2008 that merges characters from Pride and Prejudice and Frankenstein.

It’s about Mary Bennet, the moralistic, foolish middle sister in Pride and Prejudice. She's 32, a spinster, and no one's ever wanted to marry her. As she's coming to grips with that reality, she falls in love with Victor Frankenstein, who's in England to create a bride for his monster. And who's probably not a good choice for a partner. --Zak Nelson, writer and bookseller

John Kessel: Sex (and Pianos) on the Moon

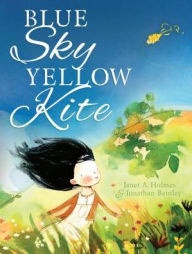

The thrill a girl named Daisy feels as a borrowed kite "swishes and swirls, dives and zooms" overcomes her with covetousness, and she runs home to hide the kite in her bedroom. When conscience gets the best of her, she finds forgiveness, a new friend... and her very own kite. Janet A. Holmes's spare text tells an all-too-familiar story of impulse and compunction, and illustrator Jonathan Bentley's lovely pencil and watercolor artwork captures the blustery, sunny days in Blue Sky Yellow Kite (Peter Pauper Press).

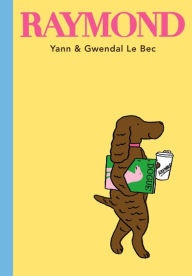

The thrill a girl named Daisy feels as a borrowed kite "swishes and swirls, dives and zooms" overcomes her with covetousness, and she runs home to hide the kite in her bedroom. When conscience gets the best of her, she finds forgiveness, a new friend... and her very own kite. Janet A. Holmes's spare text tells an all-too-familiar story of impulse and compunction, and illustrator Jonathan Bentley's lovely pencil and watercolor artwork captures the blustery, sunny days in Blue Sky Yellow Kite (Peter Pauper Press). Raymond, a well-loved chocolate-colored pooch, wonders one day if maybe there's more to life than having his ears scratched in just the right place. In no time, he's on two feet, enjoying "cappuccino-and-cupcake Saturdays" and working as a "rover-ing reporter" at Dogue magazine. But oh, the stress! With their cartoon illustration style and straight-faced humor, French brothers Yann and Gwendal Le Bec poke gentle fun at Type A humans in Raymond (Candlewick). The tongue-lolling, tail-wagging joy of his return to four-footed outdoor fun is palpable.

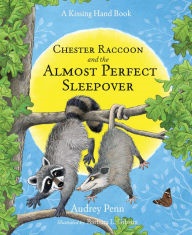

Raymond, a well-loved chocolate-colored pooch, wonders one day if maybe there's more to life than having his ears scratched in just the right place. In no time, he's on two feet, enjoying "cappuccino-and-cupcake Saturdays" and working as a "rover-ing reporter" at Dogue magazine. But oh, the stress! With their cartoon illustration style and straight-faced humor, French brothers Yann and Gwendal Le Bec poke gentle fun at Type A humans in Raymond (Candlewick). The tongue-lolling, tail-wagging joy of his return to four-footed outdoor fun is palpable. Chester Raccoon (the Kissing Hand series) returns in Chester Raccoon and the Almost Perfect Sleepover (Tanglewood Books), this time for an "overday" with Pepper Opossum and other nocturnal buddies. They hang from their tails, play Follow the Leader and eat "delicious" snacks of grubs and rotten fruit. But when bedtime comes, Chester is hit with a case of homesickness. Luckily, Mrs. Opossum knows just what to do. Audrey Penn's reassuring story and Barbara L. Gibson's playful illustrations hit the mark for any reader who is almost ready for sleepovers. --Emilie Coulter, freelance writer and editor

Chester Raccoon (the Kissing Hand series) returns in Chester Raccoon and the Almost Perfect Sleepover (Tanglewood Books), this time for an "overday" with Pepper Opossum and other nocturnal buddies. They hang from their tails, play Follow the Leader and eat "delicious" snacks of grubs and rotten fruit. But when bedtime comes, Chester is hit with a case of homesickness. Luckily, Mrs. Opossum knows just what to do. Audrey Penn's reassuring story and Barbara L. Gibson's playful illustrations hit the mark for any reader who is almost ready for sleepovers. --Emilie Coulter, freelance writer and editor

How do you define science fiction?

How do you define science fiction? On the night of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested for breaking and entering into the Democratic National Committee's headquarters at the Watergate complex. Two years later, Richard Nixon resigned rather than face certain impeachment. The story of how a bungled burglary overthrew a president began with a trail of money that connected Nixon's Committee to Reelect the President and the Watergate break-in. Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post helped bring the scandal to public light. Their anonymous source, whom Woodward met in a parking garage several times between June 1972 and January 1973, revealed that Watergate's roots lay in the highest branches of the Federal government.

On the night of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested for breaking and entering into the Democratic National Committee's headquarters at the Watergate complex. Two years later, Richard Nixon resigned rather than face certain impeachment. The story of how a bungled burglary overthrew a president began with a trail of money that connected Nixon's Committee to Reelect the President and the Watergate break-in. Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post helped bring the scandal to public light. Their anonymous source, whom Woodward met in a parking garage several times between June 1972 and January 1973, revealed that Watergate's roots lay in the highest branches of the Federal government.