|

| photo: Clayton Hauck |

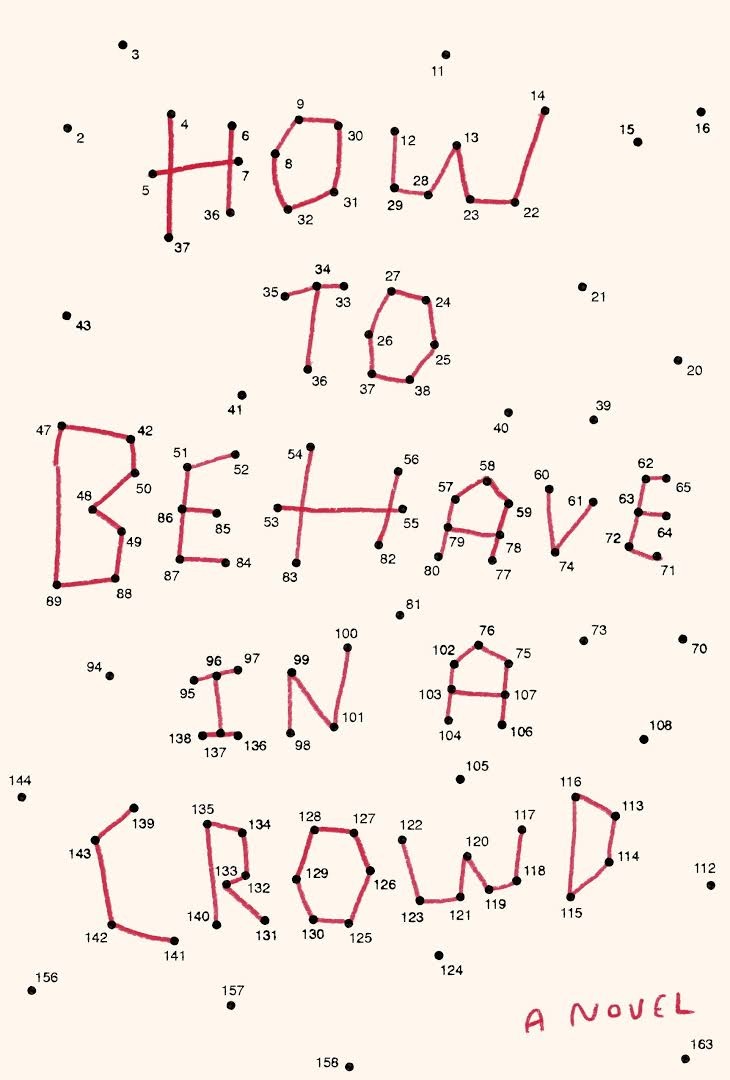

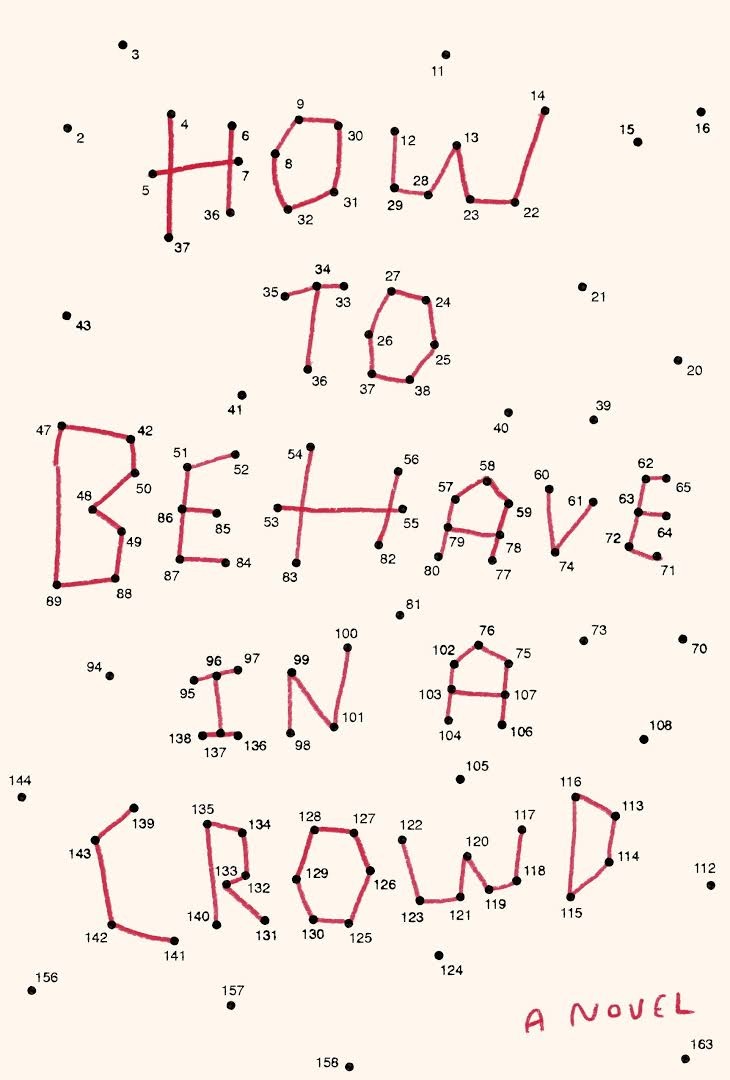

Camille Bordas is the author of three novels and her fiction has appeared in the New Yorker. Born in France and raised in Mexico City, Bordas now lives in Chicago with her husband. How to Behave in a Crowd (reviewed below), her first novel written in English, is the story of Isidore Mazal and his strange, precocious family.

How to Behave in a Crowd has been hailed as "a darkly comedic novel about the confusions of adolescence," but there is so much more to it than that one sentence could possibly convey.

Summarizing the story is always a bit hard, because it covers about three years in the life of this boy, Isidore--the major and the minor things that happen to him in that time span. Also, I don't want to give away any spoilers! But you could say it's about the adventures of a boy who keeps trying (and failing) to run away from home in search of adventure. Isidore keeps wanting to see what's beyond his home life and the silence and the constantly shut doors of his five super-smart academic siblings, but he's always drawn back to them. His brothers and sisters fascinate him, because they seem to know everything and to have life figured out. As the story progresses, though, it ends up looking like the family, which seemed so sturdy at first, might be more of an emotional Ponzi scheme in which everyone thinks the others are doing great and therefore continues with business as usual, until Isidore realizes that his siblings are all just pretending they know what they're doing, and the whole thing collapses.

This was the first book you wrote in English. Did writing in a different language change your writing process in any way?

I didn't find the process of writing a novel in English that much different, or harder, than writing a novel in French. That's probably because I see the process of writing a novel pretty much exactly as E.L. Doctorow describes it--similar to driving at night in the fog: you can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way. It makes the whole endeavor seem both vertiginous and not at the same time. You never know where you are, or where exactly you're headed, but the way to get there is one sentence at a time, so that's a manageable unit--and that's how I wrote this novel, same as I would have in French, one sentence at a time.

Obviously, having not grown up speaking English but having learned it in my late teens, there will always be words or phrases that I won't only not know, but also not know that I don't know, so that can be a little paralyzing if I think about it too much. I guess it can all be either extremely freeing or frustrating, depending on the kind of workday I'm having. I have fewer tools than a native speaker, for sure, but I make do with what I've got. To riff on the Doctorow image, I feel that not being a native English speaker only means that my headlights are maybe a little dimmer than those of an American writer, but in a way that might be advantageous: it forces me to be even more focused and precise.

Isidore is such a wonderfully drawn character. He often seems to have no idea what's going on around him, but also has moments of great clarity and wisdom. How did you get into the mind and spirit of an 11-year-old boy?

Isidore is such a wonderfully drawn character. He often seems to have no idea what's going on around him, but also has moments of great clarity and wisdom. How did you get into the mind and spirit of an 11-year-old boy?

By writing the book! My books get written one sentence at a time, and characters emerge that way as well. It took me a while to know who Isidore was. No character has ever come out of my imagination fully formed--as I put them in different situations to which they have to respond one way or another, their voices become clear. The questions are not, "What is it like to be an 11-year-old boy?" but more, "Would Isidore say this or that?" You never can fully be in someone else's head, know what it is to be them, but the more you spend time with them, the closer you get to having a glimpse of that.

But I guess I've made this question take a weird philosophical turn, when the simple, down-to-earth answer to it is probably that I remember being 11, 12, 13 years old very vividly. The sense memories of it are particularly strong: a constant discomfort, a feeling that things are going too slow, the loneliness of growing up, the impossibility of knowing if you're the first person to think a thing or if it's part of the process for all of us, the impossibility of knowing if everyone else is having a weird time too. In many ways, I feel out of touch with my teenage self and don't really know who that person was, but at the same time, I know that I haven't changed much since then. I've just had experiences pile up. That's why I liked writing a teenage character: Isidore's brain is fully formed, but not yet shaped by experience, so he mostly doesn't know what to do with it. It's like a useless superpower.

The novel features a 100-year-old woman, Daphne, who has lived so incredibly long--especially in comparison to Isidore's short 11 years. Did you intend for the novel to be an exploration of age and how it shapes our understanding of the world?

I never see my characters as vessels through which to explore any particular issue. I never intend much more in building them--and in this case, in writing Daphne--than to present full people who have something to say, or sometimes nothing to say, but in a funny way. They don't stand for anything other than themselves.

Something that I noticed in the United States, since I moved here, is that it is rare to witness much in the way of intergenerational friendships. In France, I have a handful of friends my parents' age and older, 70-somethings. I was friends with my grandparents. What interested me in Daphne was not so much her age itself (though the dissonance between her range of experience and Izzie's relatively clean slate was a great source for dialogue) but more the fact that she lived a normal life that only started becoming abnormal because of its length--a length that people start attributing meaning to when there isn't any. She becomes a receptacle for people's fears and hopes about old age, and that's problematic because she doesn't have any particular wisdom to offer.

It's clear that the Mazal family loves Isidore in their own ways, and Isidore knows that. And yet he keeps trying to run away from home. Why is that?

Isidore's case is complicated because it's unclear whether he really wants to run away or not. One minute he says he wants to be his own man, separate from his brothers and sisters, the next he says he only wishes to run away to please his mother, who's always complaining her children are not adventurous enough. I think, at the beginning of the novel at least, that it's more a desire to be noticed and find his own place in the family than to leave it. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

Camille Bordas: Finding One's Place

One of my favorite summer reads this year has been Slow Art, which was born from Reed's personal response, over the course of eight years, to Édouard Manet's painting Young Lady in 1866: "Gradually I came to understand that the image displayed--or, better, performed--a certain mystery. Not the hidden, but the visible.... I found myself drawn to the picture, resisted by it, and then drawn back. How long, I mused, could I sustain this conversation? I hardly thought about where I was being led, and certainly never imagined how often I would return to the spot, whether in my imagination or in fact."

One of my favorite summer reads this year has been Slow Art, which was born from Reed's personal response, over the course of eight years, to Édouard Manet's painting Young Lady in 1866: "Gradually I came to understand that the image displayed--or, better, performed--a certain mystery. Not the hidden, but the visible.... I found myself drawn to the picture, resisted by it, and then drawn back. How long, I mused, could I sustain this conversation? I hardly thought about where I was being led, and certainly never imagined how often I would return to the spot, whether in my imagination or in fact." I've been reading Slow Art with pleasure and patience. In fact, this seems to be my summer of the slow, concentrated read, beginning auspiciously with Martha Cooley's wonderful Guesswork: A Reckoning with Loss. Though linked in theme, her essays deserve to be savored individually, letting time pass slowly and quietly on the page as it does in the tiny Italian village where she lives part of the year. "For my own part, I have been practicing wordlessness," Cooley writes. "It is not a usual human art. Most people lack regular opportunities to try it."

I've been reading Slow Art with pleasure and patience. In fact, this seems to be my summer of the slow, concentrated read, beginning auspiciously with Martha Cooley's wonderful Guesswork: A Reckoning with Loss. Though linked in theme, her essays deserve to be savored individually, letting time pass slowly and quietly on the page as it does in the tiny Italian village where she lives part of the year. "For my own part, I have been practicing wordlessness," Cooley writes. "It is not a usual human art. Most people lack regular opportunities to try it." My third brilliant and exquisitely languid summer read is Mathias Énard's Prix Goncourt-winning novel Compass (translated by Charlotte Mandell), an intricate, breathtaking interior monologue exploring "Orientalism" through the fevered perspective of a bedridden, insomniac musicologist in his book-cluttered Vienna apartment ("I don't throw anything out, and yet I lose everything. Time strips me bare."). It may not sound like beach read material, but Compass is absolutely mesmerizing and revelatory.

My third brilliant and exquisitely languid summer read is Mathias Énard's Prix Goncourt-winning novel Compass (translated by Charlotte Mandell), an intricate, breathtaking interior monologue exploring "Orientalism" through the fevered perspective of a bedridden, insomniac musicologist in his book-cluttered Vienna apartment ("I don't throw anything out, and yet I lose everything. Time strips me bare."). It may not sound like beach read material, but Compass is absolutely mesmerizing and revelatory.

Isidore is such a wonderfully drawn character. He often seems to have no idea what's going on around him, but also has moments of great clarity and wisdom. How did you get into the mind and spirit of an 11-year-old boy?

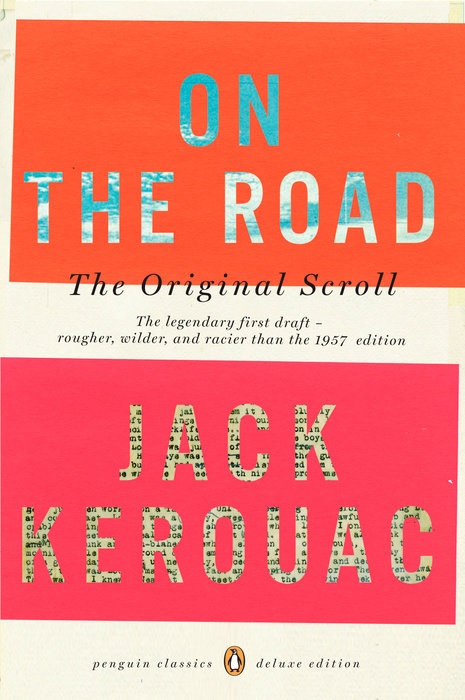

Isidore is such a wonderfully drawn character. He often seems to have no idea what's going on around him, but also has moments of great clarity and wisdom. How did you get into the mind and spirit of an 11-year-old boy? September 5, 2017 marks 60 years since the original publication of On the Road, Jack Kerouac's road trip roman à clef and one of the Beat Generation's three best known works--alongside Allen Ginsberg's Howl and William S. Burroughs's Naked Lunch. On the Road brings Kerouac's kinetic prose to a series of trips with Neal Cassady, called Dean Moriarty, through late-1940s America. Kerouac, as Sal Paradise, and Moriarty meet other Beat figures and many women on several drug and jazz-fueled jaunts across the United States and Mexico. Fast-living Dean is the catalyst to Sal's travels, separated in five parts, on an aimless but energetic search for a greater meaning to life, though tinged with a certain sadness at never being able to find it.

September 5, 2017 marks 60 years since the original publication of On the Road, Jack Kerouac's road trip roman à clef and one of the Beat Generation's three best known works--alongside Allen Ginsberg's Howl and William S. Burroughs's Naked Lunch. On the Road brings Kerouac's kinetic prose to a series of trips with Neal Cassady, called Dean Moriarty, through late-1940s America. Kerouac, as Sal Paradise, and Moriarty meet other Beat figures and many women on several drug and jazz-fueled jaunts across the United States and Mexico. Fast-living Dean is the catalyst to Sal's travels, separated in five parts, on an aimless but energetic search for a greater meaning to life, though tinged with a certain sadness at never being able to find it.