|

| photo: Isabel Fowler |

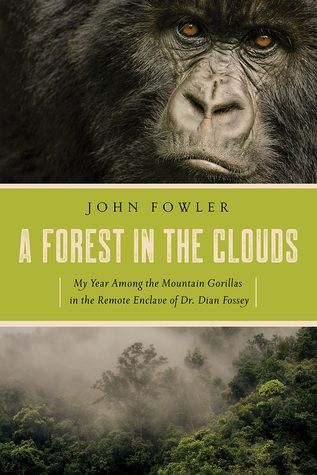

John Fowler holds a B.S. in Zoology from the University of Georgia and an M.S. in Technology and Science Policy from Georgia Tech. Fowler appeared in the pages of Dian Fossey's classic Gorillas in the Mist and in Farley Mowat's Woman in the Mists. After 21 years working in zoological parks, he is now a research professional in Tallahassee, Fla. A Forest in the Clouds: My Year Among the Mountain Gorillas in the Remote Enclave of Dr. Dian Fossey (reviewed below), a memoir about his experience as Fossey's research assistant, is his first book.

You say you weren't really qualified to be a student research assistant when you first traveled to Rwanda, yet Dr. Terry Maple seemed confident and made great efforts on your behalf.

I have never really discussed that with Terry, but I think that for him it was more intuitive on his part than anything. He knew me from his study-abroad program the previous summer, and I think my enthusiasm may have played a part. We had a good rapport, and I think he was always looking for potential grad students he could mentor and develop. I'm sure the timing of the opportunity played a role as well. Other than that, he wasn't certain of anything, and just took a chance on me.

As it turned out, I was qualified to be what Dian wanted as a student research assistant, with "assistant" being the key word. I realized eventually that independent research students working on their theses in a graduate program should've taken precedence over an undergrad like myself, but that hadn't fit well with Dian's needs, which by then were more of an occupancy of her territory and the battling of poachers rather than conducting research. Dian's people skills were combative and resentful and with her departure imminent, she could neither work collaboratively nor relinquish control, and needed to have what she thought were her own loyal people in place. That said, it was a phenomenal learning experience for an undergraduate in zoology like myself and I made the most of it, including getting credit for it toward my undergrad degree.

Heading into Rwanda, I was blissfully ignorant of what I was getting myself into and I didn't heed the warnings about those who hadn't lasted there. Upon arrival, I soon learned Dian was the biggest obstacle to overcome, and realized why others came and went. I didn't want to become one of those statistics. I stuck it out because I had made a commitment to Terry, and to Dian, too, to stay for a year. Even with all the conflict and adversity, I knew what a special opportunity it was and how worthy the gorillas were of our efforts. I also knew I would regret having left early if I did. Terry Maple would also point out that my airfare ticket to Rwanda was one-way only.

Your depictions of the environment and all of the amazing wildlife are very vivid.

Those images are still with me, perhaps even more vivid having written them down. I also still have my field notes, letters and photographic slides which I used to corroborate the memories. There were things I had nearly forgotten, but recalled upon re-examining my notes and letters and photos. Some of the events I took directly from these, like encounters with the forest elephants. That's how I could recount the details of how many there were, the sizes and who had tusks. Re-creating the world of Karisoke and those experiences are what drove my writing of this book. I even wanted to re-create Dian as the most astonishing creature of all at the center of that world. I knew there had yet to be a full-rounded written portrayal of her, up close and personal.

Readers are certain to fall in love with the gorilla Bonne Année from your captivating descriptions. What are your most meaningful memories of her?

Readers are certain to fall in love with the gorilla Bonne Année from your captivating descriptions. What are your most meaningful memories of her?

Seeing her for the first time, her plaintive, sincere face, and the way she grasped me with arms and legs when I first picked her up is what comes to mind. I can even remember her celery breath. Another poignant recollection is the moment she tried to feign an interest in feeding among the members of Group 5, which Dian described as "displacement behavior." It was a heartbreaking scenario. She was in the middle of a full assault, but was just trying to fit in as if nothing was happening, much like a new school kid might do while being bullied by others in the lunchroom.

The allure and great work of zoos enticed you to join the Audubon Zoo after Karisoke. What important things do you see happening today?

The first thing I noticed was the improvement of conditions for zoo animals. Bars and concrete were giving way to grass and shrubs and open spaces. This became a better experience for zoo-goers as well, and a better platform from which to provide public awareness about animals and their habitats. I see public education and awareness as a great contribution of zoos, as well as their work to preserve species. A zoo or aquarium is where humans can first see animals not familiar to them, and where they can develop appreciation for myriad other species that occupy the same planet. Those places accredited by the American Zoo and Aquarium Association have to maintain high standards for animal care, as well as education, research and conservation components. I was an AZA Professional Fellow for most of my career as a zoo curator, and can attest to the standards.

While at Zoo Atlanta, I was proud to coordinate the release of peregrine falcons into the city of Atlanta. This was a project initiated by the zoo in a cooperative effort with state and federal agencies. As a zoo, we contributed our animal husbandry and publicity skills to turn a cityscape into habitat for an endangered species. As a result, Atlanta is proud to host a resident breeding pair of the once endangered peregrine falcon. Many years later, a pair of these once-rare birds still nests and raises new young each year in downtown Atlanta.

This effort parlayed into our raising bald eagle chicks for release into the state of Georgia. It took our understanding of captive animal breeding and hand-rearing to make that possible, as well as the public outreach for which zoos must succeed at to generate revenues. We had the expertise for raising the birds from babies, and the state provided a wild release site on the coast. Zoo Atlanta's promotion of the effort brought well-deserved recognition for Georgia's commitment to re-establishing wild populations of this bird, which is our national symbol, by the way. Thanks to these kinds of efforts, the bald eagle, which was once absent from most states, has recovered well and is no longer listed as an endangered species.

Since you've answered the question you set out to, is A Forest in the Clouds the beginning and the end of your writing career?

I don't have another true story with all the spectacle and complexity of A Forest in the Clouds but now that I've honed my writing skills, I'd love to bring the zoo world to life, perhaps in fiction. Let's see what happens next. --Jen Forbus, freelance

John Fowler: An Inside Look at Dian Fossey

Beverly Jenkins is known for her powerful portrayals of black characters and her latest, Tempest (Avon, paperback), is an Old West–meets–new love tale. Mail-order bride Regan Carmichael thinks she has everything figured out--until she meets her intended, widower Dr. Colton Lee, who's sure his days of romance are behind him.

Beverly Jenkins is known for her powerful portrayals of black characters and her latest, Tempest (Avon, paperback), is an Old West–meets–new love tale. Mail-order bride Regan Carmichael thinks she has everything figured out--until she meets her intended, widower Dr. Colton Lee, who's sure his days of romance are behind him. Set in Venice, Victoria Alexander's The Lady Travelers Guide to Larceny with a Dashing Stranger (Harlequin, paperback) finds Lady Wilhelmina Bascombe searching for a priceless family treasure in order to shore up her dwindling bank account. There's only one problem: Dante Augustus Montague believes the painting belongs to him, and he'll stop at nothing to retrieve it--even going so far as to fall in love.

Set in Venice, Victoria Alexander's The Lady Travelers Guide to Larceny with a Dashing Stranger (Harlequin, paperback) finds Lady Wilhelmina Bascombe searching for a priceless family treasure in order to shore up her dwindling bank account. There's only one problem: Dante Augustus Montague believes the painting belongs to him, and he'll stop at nothing to retrieve it--even going so far as to fall in love. Laura Lee Guhrke offers up a delicious wallflower and rake pairing in The Trouble with True Love (Avon, paperback). Poor prim Clara Deverill ends up right in the path of Rex Galbraith, reprobate par excellence. Will she give way, or stand up for love? Suzanne Enoch's Scottish-set historicals never disappoint, and A Devil in Scotland (St. Martin's, paperback) is a fine example of why. Lush settings, rapier wit and two well-drawn characters will leave you sighing with delight long after this second-chance-at-love story has ended. --Stefanie Hargreaves, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Laura Lee Guhrke offers up a delicious wallflower and rake pairing in The Trouble with True Love (Avon, paperback). Poor prim Clara Deverill ends up right in the path of Rex Galbraith, reprobate par excellence. Will she give way, or stand up for love? Suzanne Enoch's Scottish-set historicals never disappoint, and A Devil in Scotland (St. Martin's, paperback) is a fine example of why. Lush settings, rapier wit and two well-drawn characters will leave you sighing with delight long after this second-chance-at-love story has ended. --Stefanie Hargreaves, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Readers are certain to fall in love with the gorilla Bonne Année from your captivating descriptions. What are your most meaningful memories of her?

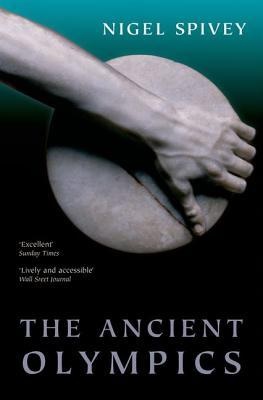

Readers are certain to fall in love with the gorilla Bonne Année from your captivating descriptions. What are your most meaningful memories of her?  The opening ceremony for the 2018 Winter Olympics airs tonight from Pyeongchang, South Korea, kicking off two weeks of skating, skiing, sledding and other sports that would have left the original Olympians scratching their heads. The city-states of Ancient Greece created the Panhellenic Games, of which the Olympics were the primary event, on a four-year cycle that celebrated culture as much as athleticism. From roughly 776 BC to 394 AD, contestants wrestled, ran and raced horses, among other events, for personal accolades and the honor of their home cities. The games were also important forums of Hellenic religious and artistic life, and became political tools for querulous city-states--though the Olympic Truce meant spectators and athletes were free to travel to the games even in times of war. After a long decline, the Ancient Olympics ended when Roman Emperor Theodosius I banned all pagan festivals. The modern games began in 1896.

The opening ceremony for the 2018 Winter Olympics airs tonight from Pyeongchang, South Korea, kicking off two weeks of skating, skiing, sledding and other sports that would have left the original Olympians scratching their heads. The city-states of Ancient Greece created the Panhellenic Games, of which the Olympics were the primary event, on a four-year cycle that celebrated culture as much as athleticism. From roughly 776 BC to 394 AD, contestants wrestled, ran and raced horses, among other events, for personal accolades and the honor of their home cities. The games were also important forums of Hellenic religious and artistic life, and became political tools for querulous city-states--though the Olympic Truce meant spectators and athletes were free to travel to the games even in times of war. After a long decline, the Ancient Olympics ended when Roman Emperor Theodosius I banned all pagan festivals. The modern games began in 1896.