|

| photo: Murdo Macleod |

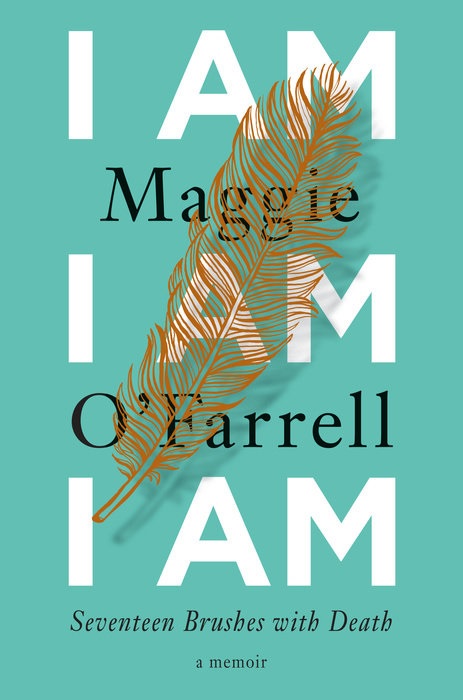

Inspired by her daughter's severe case of anaphylaxis, Costa Novel Award-winning author Maggie O'Farrell's memoir, I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death (Knopf, February 6, 2018), explores her close encounters with death, in forms that range from her childhood encephalitis to a chance meeting with an apparent serial killer. O'Farrell's (The Hand That First Held Mine) candor and grace render these stories both sobering and life-affirming.

You've published seven novels since 2000, but this is your first work of nonfiction. What were some of the challenges in writing a memoir?

I always planned to never write a memoir. I never thought I would write about myself in that way. I've always been uncomfortable with the idea of exposing so much about yourself. The genre of memoir can also be a huge tax on your friends and family. But you don't necessarily choose the book, the book chooses you. This book just appeared in the back of my notebooks. I was so reluctant about it that when I signed the contract in the U.K., I said I didn't want an advance for it, because I didn't know whether I was going to finish it or, if I did, whether I was going to publish it. My agent told me I had to be paid something to make it legal, so I asked for £1.

What led to your decision to structure the memoir as 17 non-chronological essays about what you call "brushes with death," each one associated with a body part or body system, rather than a more conventional narrative?

As a writer of fiction, chronology is never something that's interested me. I find it quite tyrannical. I don't think our brains, our memories, our personalities work like that. Coming up with the structure was quite liberating for me. Not only did the format of these episodes release me from the tyranny of chronology, it allowed me to leave quite a bit out, including not having to expose other people who don't have a right of reply to what I write.

You have three children, and you've said that you wrote this book to help them understand that your daughter's health challenges, including an extreme risk of anaphylactic shock, aren't abnormal. They're still perhaps too young to absorb that message fully, so how have you dealt with it, if at all, in their lives so far?

The book was written because my daughter suffers this life-threatening immune disorder, something we grapple with on a daily basis, the idea of keeping her alive. If one member of a family has a disability or health problem, it's something that's shared by the whole family. As the mother, you have to think about how it affects the other two children. The book was an attempt to try to make sense of what my daughter is going through, what it's like to come so close to death, to feel your body conspiring against you, but also what it's like to be close to someone you love in that condition, what it's like for my other children to deal with that.

Your own childhood was profoundly affected by a bout of encephalitis at age eight. Can you describe how that's shaped the rest of your life, both physically and emotionally?

Your own childhood was profoundly affected by a bout of encephalitis at age eight. Can you describe how that's shaped the rest of your life, both physically and emotionally?

It's quite hard to imagine what I would have been like without that experience. It happened at such a young age that it's always felt very much a part of me. In a lot of ways, I don't know where my encephalitis begins and where I end. There are so many things in my physical being that seem completely normal to me that I realize to other people aren't normal. I wouldn't describe what I have as disabilities; they're mild incapabilities, perhaps. I just get on with it. Someone once asked me, if you could wave a magic wand and wish that you didn't have encephalitis as a child, would you do it? And I don't know. Coming so close to death at such a young age, and hearing people talk about it, I think gives you a very strong sense of living on borrowed time, that it's a bit extra, and that I need to make the most of it. It could have made me quite a cautious person, quite fearful, but in fact it had the opposite effect. I think it made me a bit too reckless, actually. And when I didn't die, the doctor said I would never walk again, never write again, but I managed to find a way out of that particular destiny. I've always felt, since then, like the luckiest person alive.

At least two of the incidents in the book involve encounters with criminals--one a likely serial killer who murdered another young woman shortly after you met him, the other a machete-wielding thief. In describing the former, you write, "Death brushed past me on that path, so close that I could feel its touch, but it seized that other girl and thrust her under." Have these incidents influenced how you feel about life's sheer fortuity?

The first instance, when I was 18, I completely buried. I never talked to anyone about it and left the area where it occurred soon afterwards. In an odd sense, I feel both quite lucky to have survived and quite guilty. It very easily could have been me, but it turned out to be someone else. One of the reasons I never talked about the incident in later life is that, in a sense, the story doesn't really belong to me, the narrative isn't mine. The central tragedy belongs to the other girl; I'm just a footnote in that chapter. And one of my impulses in writing that chapter was to protect her. As a novelist, you can have complete ownership. In a memoir, it's much more nuanced and complicated.

You write, "We are, all of us, wandering about in a state of oblivion, borrowing our time, seizing our days, escaping our fates, slipping through loopholes, unaware of when the axe may fall." Have your near-death experiences made you more mindful, more appreciative of life?

From a very young age, I've had a sense of the frailty of human existence. That we all hang by a thread; that we all could take a few steps in the wrong direction; that we could take the wrong path; that we could meet the wrong person and that's it, it's all over. Probably more than most people, I have a stronger sense of how temporary it all is and how fragile we all are, but also how strong. There's a huge amount of strength in our frailty.

In many ways, I Am, I Am, I Am is quite a life-affirming book, but what do you say to readers who might be inclined to avoid it because they consider the subject matter morbid or depressing?

Even though the subtitle includes the word "death," the book is really about life. It's about how we carry on, why it's important to live your life to the fullest. This is something I say to my daughter when she feels upset about what she's going through: "Everybody has something they're struggling with, that challenges them." We've all just got to try to live the best life we can, live the biggest life we can. We all have strictures around us, whether they're physical or financial, spiritual, geographical or social. Everybody has to do the best. We all have to seize the day, because we're all only here for a short time. --Harvey Freedenberg, attorney and freelance reviewer

Maggie O'Farrell: Close Encounters with Death

In Willy Vlautin's novel Don't Skip Out on Me (HarperCollins), Horace Hooper is a lost young man living a hard but also secure life on a Northern Nevada ranch. He's itchy to move beyond safety and prove himself as a boxer. This isn't a good plan, but it propels him on a tough, compelling journey from Tucson to Mexico to Las Vegas in search of his own elusive place in the world.

In Willy Vlautin's novel Don't Skip Out on Me (HarperCollins), Horace Hooper is a lost young man living a hard but also secure life on a Northern Nevada ranch. He's itchy to move beyond safety and prove himself as a boxer. This isn't a good plan, but it propels him on a tough, compelling journey from Tucson to Mexico to Las Vegas in search of his own elusive place in the world. Growing up in an Idaho mountain landscape offered a beautiful sense of place for Tara Westover, but her strict Mormon fundamentalist family tempered nascent dreams. In Educated: A Memoir (Random House), she chronicles how she was able to transcend minimal home schooling and her restrictive upbringing to achieve academic success at Brigham Young University and the University of Cambridge.

Growing up in an Idaho mountain landscape offered a beautiful sense of place for Tara Westover, but her strict Mormon fundamentalist family tempered nascent dreams. In Educated: A Memoir (Random House), she chronicles how she was able to transcend minimal home schooling and her restrictive upbringing to achieve academic success at Brigham Young University and the University of Cambridge. In The Unmade World (Unbridled Books), Steve Yarbrough shows how place can become a web as the intense story moves from Krakow to California to the Hudson Valley, with Poland threading through the narrative. Colm Toibin nailed it when he wrote that this "many-layered novel is a thriller, a love story, a travelogue full of richly observed scenes from Polish and American life, a morality tale replete with betrayal, remorse and lust for revenge, and a hilarious comedy."

In The Unmade World (Unbridled Books), Steve Yarbrough shows how place can become a web as the intense story moves from Krakow to California to the Hudson Valley, with Poland threading through the narrative. Colm Toibin nailed it when he wrote that this "many-layered novel is a thriller, a love story, a travelogue full of richly observed scenes from Polish and American life, a morality tale replete with betrayal, remorse and lust for revenge, and a hilarious comedy." Sense of place is intensely multilayered in Peter Carey's novel A Long Way From Home (Knopf, Feb. 27). During the 1950s, Willie Bachuber, a man devoted to maps, takes part in the Redex Trial, a 10,000-mile car race through the unforgiving Australian outback. There he is confronted with equally unforgiving revelations about his personal and cultural history that no map could chart.

Sense of place is intensely multilayered in Peter Carey's novel A Long Way From Home (Knopf, Feb. 27). During the 1950s, Willie Bachuber, a man devoted to maps, takes part in the Redex Trial, a 10,000-mile car race through the unforgiving Australian outback. There he is confronted with equally unforgiving revelations about his personal and cultural history that no map could chart.

Your own childhood was profoundly affected by a bout of encephalitis at age eight. Can you describe how that's shaped the rest of your life, both physically and emotionally?

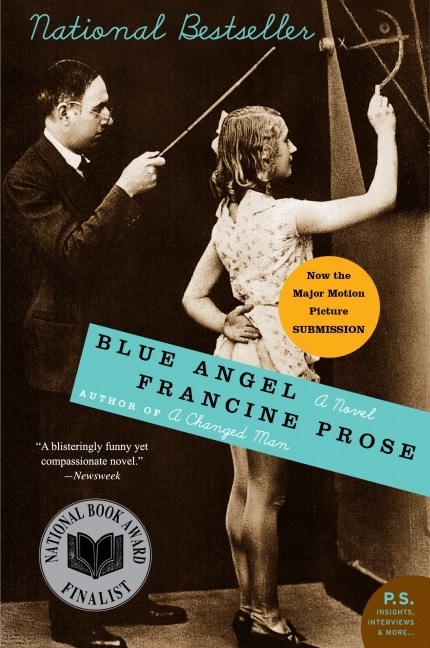

Your own childhood was profoundly affected by a bout of encephalitis at age eight. Can you describe how that's shaped the rest of your life, both physically and emotionally? Author, essayist and book critic Francine Prose's Blue Angel (2000) is coming to select theaters on March 9. Submission, adapted and directed by Richard Levine, stars Stanley Tucci as creative writing professor Ted Swenson, whose deeply rooted cynicism is challenged by an unexpectedly gifted undergrad. It's been decades since Swenson last published a novel, and the dreary routine of reading poorly written student manuscripts and putting up with the smugness of his fellow professors has left him complacent. Angela Argo (played by Addison Timlin) seems like yet another undergrad with more enthusiasm than literary ability. But when she privately shares a draft of her novel, Swenson discovers the first potentially great writer he's ever taught. The fact that her work revolves around a romance between a teacher and student slips his mind, at first, until Swenson's obsession with his pupil turns disastrously inappropriate. His good intentions, if stupid actions, culminate in campus-wide humiliation, desertion by his family and colleagues, and a sexual harassment hearing of farcical proportions.

Author, essayist and book critic Francine Prose's Blue Angel (2000) is coming to select theaters on March 9. Submission, adapted and directed by Richard Levine, stars Stanley Tucci as creative writing professor Ted Swenson, whose deeply rooted cynicism is challenged by an unexpectedly gifted undergrad. It's been decades since Swenson last published a novel, and the dreary routine of reading poorly written student manuscripts and putting up with the smugness of his fellow professors has left him complacent. Angela Argo (played by Addison Timlin) seems like yet another undergrad with more enthusiasm than literary ability. But when she privately shares a draft of her novel, Swenson discovers the first potentially great writer he's ever taught. The fact that her work revolves around a romance between a teacher and student slips his mind, at first, until Swenson's obsession with his pupil turns disastrously inappropriate. His good intentions, if stupid actions, culminate in campus-wide humiliation, desertion by his family and colleagues, and a sexual harassment hearing of farcical proportions.