|

| photo: Ben Arons |

Jordanna Max Brodsky hails from Virginia, where she made it through a science and technology high school by pretending it was a theater conservatory. She holds a degree in history and literature from Harvard University and is the author of the Olympus Bound trilogy and The Wolf in the Whale (Redhook, $15.99), which is reviewed below. Brodsky lives with her husband in Manhattan, where she is working on her next novel.

The Wolf in the Whale is a complex, epic novel. What was your process for writing something this grand in scale?

I can't even tell you how long this book took because I literally don't know. It was the first book I ever started to write, which at the time was like, "What am I doing? This is an incredibly hard book to write." But the story just grabbed hold of me, so I spent time researching and writing. And it was the first book I brought to my agent, who was interested, but said, "You know what, this is a very strange book, so do you have any other ideas?" And I told her about my idea for The Immortals (Book 1 of the Olympus Bound trilogy). She said, "Well, that one's an easier sell. Why don't you work on that one?" And so I did; I finished that trilogy and then came back to this book. At that point, I did a lot more editing, rewriting, researching, travel, all the rest of it before it was finally done. So, it's been over 10 years on and off with a big break in the middle.

Part of your process also includes very hands-on research. Why is that so important to you?

It always adds a richness that you can't quite get any other way. Certainly in terms of going up to the Nunavut Territory in northern Canada (where the book is set) and speaking with Inuit folk up there, it was the least I could do. To tell a story inspired by their culture, I felt like it was obligatory to do my best to engage as much as possible with the modern community. Even though this story is set a thousand years ago, it's definitely still their history, their past. I would have preferred to go up there and live for two years.

Plus, there's the actual experiences. I had written the Northern Lights scene in the book long before I ever went up to Nunavut--before I'd ever seen the Northern Lights in person. I'd watched a million videos, seen a million photographs. You feel like, "how different could it really be in person? Surely you can write it without going up there." And I did, I wrote it originally without having been there. Then, when I was actually standing there under the Northern Lights, the whole thing was completely different. I knew the Inuit legend that the Northern Lights are the ancestors of the dead playing kickball games in the sky. But I didn't really get it until I was standing there looking at the sky, and saw these flashes of orange and purple kind of coming toward me with these green shadows. And then, all of a sudden, that's when I saw this stripe of green slither cross the sky and it was my husband who turned to me and said, "It looks like a snake." And I thought, "oh my God, that's the world serpent." And so all those moments, all those details in that scene come from having experienced it myself.

In all of your books, gender plays a very prominent role. What were your goals with Omat, who in the ancient Inuit culture is believed to be a female possessing the soul of a male?

In all of your books, gender plays a very prominent role. What were your goals with Omat, who in the ancient Inuit culture is believed to be a female possessing the soul of a male?

The challenge here was to try to present an understanding of gender and of gender roles that's extremely different from our own modern conceptions--and I think very different from modern Inuit conceptions as well. This is not a practice, as far as I know, that's still done in modern Inuit culture. But it was one that did exist pre-Christianity in certain locations and among certain communities.

I can see it even as different reviewers start to write about the book. They're struggling with how to talk about the idea of gender and should they use our modern transgender conventions, which is not my intention in this book. Omat is not what we today call transgender--it's a very different sort of thing. Although I think that's the beauty of it. There are all these different varieties of what gender means. Part of the struggle, I think, is in Inuit language there are no gender pronouns--there's no he or she. (I had to use these pronouns, otherwise I felt like the book would have been extremely confusing for modern readers. But again, they wouldn't have.)

Yet they have a society that is so gendered.

Yes. Different rules, different taboos for different genders, and yet there exist these people who are able to transcend that due to their birth.

Are there any other realms of history and mythology on your radar for the future?

I studied American history and literature in college, and that's really my first love. My next project is an American historical fiction book set during the Civil War. It will actually not have a mythological component for once. I'm taking a little bit of a step back from mythology and delving a little more into history, although issues of gender and gender relations and what it means to be a woman in different ages, that is still going to be a major theme of the book. Some of my favorite themes I just can't get away from. But when dealing with the American Civil War, I tend to believe that the reality of it is complex enough and important enough that there is no need to bring in any fantastical elements. As fun as it is to have Abraham Lincoln be a vampire hunter, I prefer to remember Southern slave owners didn't have supernatural causes to enslave Africans. There were plenty of human reasons to be evil and immoral and I don't think we should give people a pass by making them supernatural monsters. --Jen Forbus

Jordanna Max Brodsky:The Complexities of Gender

Although Harper isn't exactly sanctimonious about language, her fabulous expertise on mental health makes this tiny book jam-packed with empathetic encouragement. Ever feel like your attempts at getting out of depression just aren't cutting it? Well: "This is because depression, along with being a motherf*cker, lies like a politician trying to convince you that drilling for oil in a national park is a good idea."

Although Harper isn't exactly sanctimonious about language, her fabulous expertise on mental health makes this tiny book jam-packed with empathetic encouragement. Ever feel like your attempts at getting out of depression just aren't cutting it? Well: "This is because depression, along with being a motherf*cker, lies like a politician trying to convince you that drilling for oil in a national park is a good idea." She's also great with life advice in general. Unf*ck Your Adulting (Microcosm, $9.95) expounds on key interpersonal skills like "Don't Be a Dick," "Forgive the People Who Don't Get It," "Stop Comparing Your Insides to Other People's Outsides" and "Don't Presume Other People's Intent."

She's also great with life advice in general. Unf*ck Your Adulting (Microcosm, $9.95) expounds on key interpersonal skills like "Don't Be a Dick," "Forgive the People Who Don't Get It," "Stop Comparing Your Insides to Other People's Outsides" and "Don't Presume Other People's Intent." Sure, some of this stuff isn't exactly groundbreaking, but it bears repeating. The brilliant essayist Kristin Dombek dives deep into our cultural obsession with narcissism in The Selfishness of Others (FSG, $13). By focusing on the fear of narcissism, she unravels the ease with which we assign malice to the actions of others while claiming victimhood. It's a provocative book-length essay that subverts a wild social trend, and I continue to reread it for Dombek's unpretentious wisdom.

Sure, some of this stuff isn't exactly groundbreaking, but it bears repeating. The brilliant essayist Kristin Dombek dives deep into our cultural obsession with narcissism in The Selfishness of Others (FSG, $13). By focusing on the fear of narcissism, she unravels the ease with which we assign malice to the actions of others while claiming victimhood. It's a provocative book-length essay that subverts a wild social trend, and I continue to reread it for Dombek's unpretentious wisdom.

In all of your books, gender plays a very prominent role. What were your goals with Omat, who in the ancient Inuit culture is believed to be a female possessing the soul of a male?

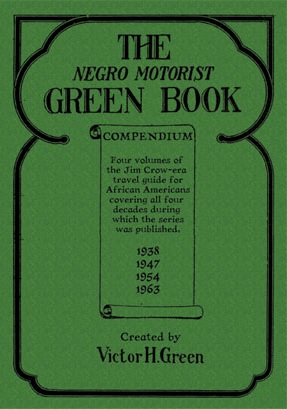

In all of your books, gender plays a very prominent role. What were your goals with Omat, who in the ancient Inuit culture is believed to be a female possessing the soul of a male? This is a stunning week for films called Green Book. One is the winner of the best picture Oscar and several other awards Sunday night. The other is The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, a documentary about the series of books published annually by Harlem postal carrier Victor H. Green between 1936 and 1966. (The Oscar-winning movie is primarily about the relationship between a celebrated black pianist and his white driver on a trip through the South, during which they use the book as a reference.) Those books, called The Negro Motorist Green Book, which the documentary calls "part travel guide and part survival guide," offered listings of hotels, restaurants, gas stations, and other businesses, many black-owned, that black travelers could use in the segregated South as well as features about car travel, new car models and more.

This is a stunning week for films called Green Book. One is the winner of the best picture Oscar and several other awards Sunday night. The other is The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, a documentary about the series of books published annually by Harlem postal carrier Victor H. Green between 1936 and 1966. (The Oscar-winning movie is primarily about the relationship between a celebrated black pianist and his white driver on a trip through the South, during which they use the book as a reference.) Those books, called The Negro Motorist Green Book, which the documentary calls "part travel guide and part survival guide," offered listings of hotels, restaurants, gas stations, and other businesses, many black-owned, that black travelers could use in the segregated South as well as features about car travel, new car models and more.