|

| photo: Nina Subin |

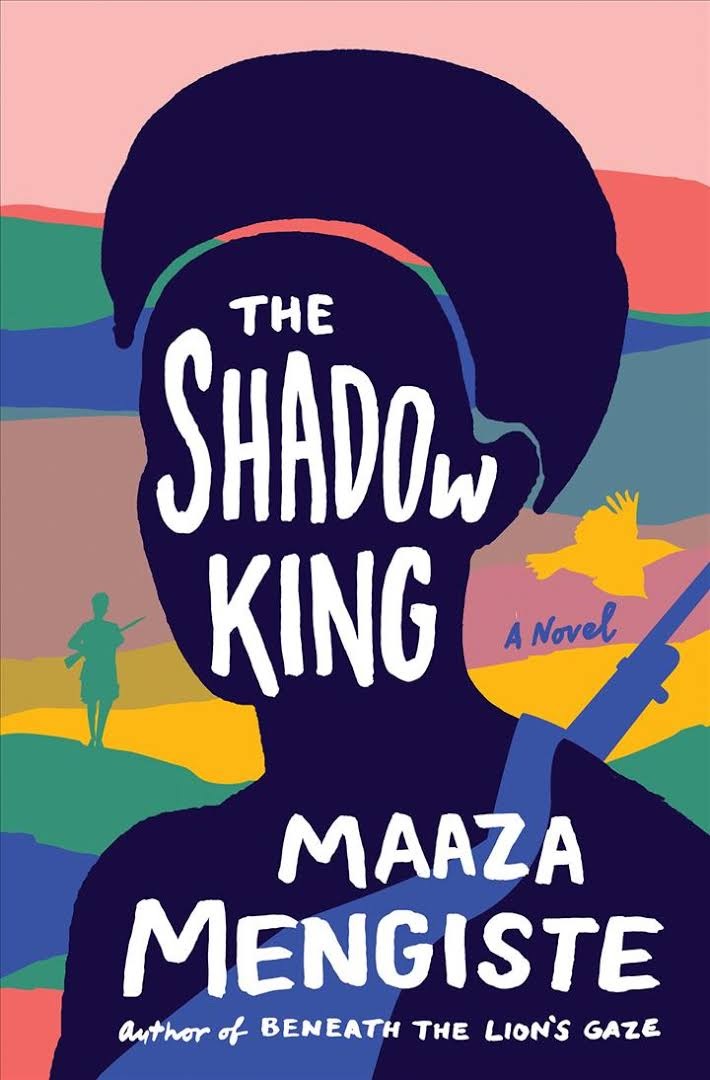

Maaza Mengiste is a novelist and essayist. Her debut novel, Beneath the Lion's Gaze, was selected by the Guardian as one of the 10 best contemporary African books and named one of the best books of 2010 by the Christian Science Monitor and the Boston Globe and other publications. Her work can be found in the New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, Granta, the Guardian, the New York Times, Rolling Stone and the BBC. The Shadow King (available now from W.W. Norton and reviewed below), is her second novel.

Tell us about the inspiration for The Shadow King.

I grew up hearing the stories of Ethiopia's fight against Mussolini's forces. The stories were epic narratives about heroism and defiance, and they fueled my young imagination. As I grew older and started to learn more about this history, I wondered about what it felt like to be in this war. As I started researching, hoping to re-create those grand stories I heard as a child, I came up against a more complicated version of conflict. I wondered who had been left out of retellings, who had been frightened, who had been a collaborator: in essence, what were the stories that no one wanted to talk about?

I also began to question the place of women in the war. All of this led me into exciting new territory and as I continued to research, I began to find stray threads of details about women who fought in the front lines. And then, quite by chance, I discovered the story of my great-grandmother, Getey, who went to war as a young girl. I realized that this history was also part of my family history--it was a history I had never known--and if one woman's story had been silenced, how many others were there? Thus The Shadow King began to form into the book it is now.

Your great-grandmother sued her father for his gun so she could enlist as a soldier. Tell us more about that. Did she help inspire the characters of Hirut and/or Aster?

Getey had a reputation as a fierce and stubborn woman, right to the end of her life. She was not afraid to express herself, and though she was petite, she could command an entire room. I remember her this way: as elderly and bedridden but in no way frail.

I was already writing about Hirut and Aster before I learned about Getey's lawsuit against her father when she was young, and then her decision to enlist in the war. I could not believe that after all of the time searching for these women who enlisted in the war, there was one in my own family! I'd heard countless stories about the men who fought, their heroics, their determination, the hardships. Why did it take so long for Getey's story to come out?

When we speak of war, we tend to speak of men and that shapes what gets remembered and also, what ultimately gets forgotten. I hope that more of these stories come to light from Ethiopia, but also from around the world, because I know they exist.

Hirut realizes at one point that "the battlefield [was] her own body" and that it has always been thus. How does the story explore bodies, especially women's bodies, as battlegrounds?

Hirut realizes at one point that "the battlefield [was] her own body" and that it has always been thus. How does the story explore bodies, especially women's bodies, as battlegrounds?

One of the ideas I wanted to explore in this book was the body as its own terrain. If we think that war "makes a man out of you," then what does it mean to fight as a woman, and what does it mean to be a man fighting next to a woman? War pits bodies against each other, but what happens when the person who should be fighting next to you decides that your body is not your own to claim and control? Who, then, is the real enemy and which war is the real war?

Hirut has to question her allegiances when she is sexually assaulted, and in declaring herself a soldier, she also declares that the war being waged on her body will come to an end. She conceives of her body as a country, and it is hers and she will fight for her own freedom from threat.

The narrative explores the gap between an image of a person--in Ettore's photographs, and in how a person is perceived--versus how they see themselves. Can you talk about this space between image and reality?

I've long been fascinated with this gap between what a photograph reveals and what it manages to conceal. If a photograph is a captured moment, what is the message it is trying to convey, and what are all those other messages it's trying to silence?

Photographs have been integral in how we imagine Africa and Africans. They have been pivotal in framing how we speak of war and what we imagine soldiers to experience, and to do, while they're fighting. While writing this book, I wanted to step into the space that exists between what's seen and what's invisible. I began with the premise that what's invisible is as potent--and often more so--than what meets the eye. I wanted the photographs to move, so to speak, to tell what was happening just before the shutter release and after. I wanted to explore what would happen if those people who were posed in front of the camera were allowed to move as we stared at the image. What, then, would I be able to truly see?

The conflict between Italy and Ethiopia is long-running and complex, but is not well known in the U.S.

It's interesting, because I think within the African American community, Ethiopia's fight for independence inspired and galvanized many. This was an African nation that defeated a European force. In Harlem, as the war started, African Americans marched, held fund-raisers, pored over news reports and even tried to enlist to fight on behalf of Ethiopia. James Baldwin speaks of being inspired by the sight of Haile Selassie, a black man as a world leader who confronted fascism.

If you look at the front pages of major newspapers in the fall of 1935, this war filled the headlines. The world was riveted. But as things dragged on, and as Hitler's threat became very apparent and World War II loomed, attention turned toward Europe. I was surprised by how intensely the world was focused on Ethiopia in 1935, and how quickly this conflict was forgotten once World War II began in earnest. I could locate articles, journalists' accounts of being in Ethiopia, books. But even in all of this, I was often finding narratives that positioned Ethiopia and Ethiopians in stereotypical ways. I had to dig past preconceived notions in order to find kernels of truth. --Katie Noah Gibson

Maaza Mengiste: Women on the Battlefield

The recent release of Margaret Atwood's long-awaited The Testaments (Nan Talese, $28.95) brings to mind the many challenges to The Handmaid's Tale (Anchor, $15.95) following its 1985 publication, according to the American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom.

The recent release of Margaret Atwood's long-awaited The Testaments (Nan Talese, $28.95) brings to mind the many challenges to The Handmaid's Tale (Anchor, $15.95) following its 1985 publication, according to the American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom. Reading is dangerous; ideas are dangerous. Banned Books Week reminds us of that fact. People have lost their lives for translating Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses. Ayatollah Khomeni issued a fatwa (a death threat) because he believed the book was critical of Islam. Yet publishers bravely continued to release Rushdie's books, including his most recent one, Quichotte (Random House, $28). Teachers and school librarians are brave enough to read aloud and share Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by J.K. Rowling (Scholastic, $12.99) and the Newbery Award-winning The Giver by Lois Lowry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $9.99), facing down parents and administrators who wish to remove such books (Rowling's book was the #1 challenged title from 2000-2009).

Reading is dangerous; ideas are dangerous. Banned Books Week reminds us of that fact. People have lost their lives for translating Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses. Ayatollah Khomeni issued a fatwa (a death threat) because he believed the book was critical of Islam. Yet publishers bravely continued to release Rushdie's books, including his most recent one, Quichotte (Random House, $28). Teachers and school librarians are brave enough to read aloud and share Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by J.K. Rowling (Scholastic, $12.99) and the Newbery Award-winning The Giver by Lois Lowry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $9.99), facing down parents and administrators who wish to remove such books (Rowling's book was the #1 challenged title from 2000-2009).

Hirut realizes at one point that "the battlefield [was] her own body" and that it has always been thus. How does the story explore bodies, especially women's bodies, as battlegrounds?

Hirut realizes at one point that "the battlefield [was] her own body" and that it has always been thus. How does the story explore bodies, especially women's bodies, as battlegrounds?  Ulysses by James Joyce is perhaps the best example of the folly that is book censorship, its history a reminder of perils of banning books rather than celebrating the freedom to read. Ulysses was serialized in the United States in the Little Review magazine between 1918 and 1921. Episode 13, "Nausicaa," was deemed obscene under the Comstock Act of 1873, effectively making Ulysses illegal in the U.S. The U.S. Post Office burned hundreds of copies throughout the 1920s. Meanwhile, in Paris, Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company sold copies to visiting Americans, many of which made their way back to the U.S. Prohibition of the book also led to erroneous pirate copies whose errors were replicated in later official versions.

Ulysses by James Joyce is perhaps the best example of the folly that is book censorship, its history a reminder of perils of banning books rather than celebrating the freedom to read. Ulysses was serialized in the United States in the Little Review magazine between 1918 and 1921. Episode 13, "Nausicaa," was deemed obscene under the Comstock Act of 1873, effectively making Ulysses illegal in the U.S. The U.S. Post Office burned hundreds of copies throughout the 1920s. Meanwhile, in Paris, Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company sold copies to visiting Americans, many of which made their way back to the U.S. Prohibition of the book also led to erroneous pirate copies whose errors were replicated in later official versions.