|

| (photo: Willy Somma) |

Anna Solomon is the author of Leaving Lucy Pear and The Little Bride. She is a two-time winner of the Pushcart Prize, and her short fiction and essays have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, One Story, Ploughshares and Slate. She is coeditor, with Eleanor Henderson, of Labor Day: True Birth Stories by Today's Best Women Writers. Solomon was born and raised in Gloucester, Mass., and lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children. Her new novel is The Book of V. (Holt, May 5, 2020).

What makes for a compelling protagonist?

A compelling protagonist is someone whose wants and desires and needs are in conflict in some way with the realities of her life. What draws me in as both a reader and as a writer is the tension that exists between the longing and the reality. I also want my protagonists to be inwardly multifarious, ambivalent in what they want. I'm interested in seeing the characters that I read and write struggle not just to get what they want but to figure out what they want.

Was one of these three women the starting point?

When I write a novel, it's almost impossible for me to remember where I began. But really, Vashti was the beginning. In a lot of ways the three women who hold the book's core for most of it--Lily, Vee and Esther--were not really where it began. It began with this banished ancient Persian queen, Vashti, who I always wondered about. I wanted to figure out how to make her absence into a presence. So it began with a question about her, but in terms of the characters forming, I'm pretty sure I began with Vivian Barr (also known in the book as Vee), who is my Vashti.

Do you have a favorite character, or one with whom you especially identify?

The answer to each of those questions is different. Certainly, in terms of her relationship to my own life, and the contours of our lives, I identify most obviously with Lily. She is the mother of two in Brooklyn, which is where I live as a mother of two. Our lives are really different from each other: Lily has given up her work, where I have not. But in a lot of ways, writing Lily felt like taking many of my own impulses and questions and exaggerating them to the hilt.

She's like alternate-reality you.

Kind of, yeah, like what would have happened if I had stopped working? What would that do to me, if I had not held onto the part of me that creates and is out in the world as an adult and a professional and an artist?

As for which I like the most or enjoyed writing the most, the one who was the most fun was Vivian Barr, in part because I got to write her in two very different parts of her life. Writing Vivian both as a young woman and as an older woman, and watching her both evolve and not evolve, was really thrilling for me as a writer. In some ways, I found her development came most easily to me.

How long does it take you to write a novel? You said you don't always remember the beginning!

That's also hard to identify by the end! In part because there are so many different stages to writing a novel. And, at least in my experience so far, in the middle of writing a novel I have another one come out in the world. And so I take time away to go introduce that book to the world, and then I come back to it. But I think it's fair to say that this novel took me three to four years to write and research and edit and rewrite, and all the rest.

I feel as if this book was created perhaps a little more efficiently than my first two, and that's probably because I did not have a baby while in the middle of writing it. It's the first book I did not have a baby while in the middle of writing.

That makes a difference, huh?

Yeah! Who knew! (We all knew.)

Your three novels each center on women chafing against limitations of their eras and cultures. How have these projects differed from one another?

When I began dreaming up this book I knew what I wanted to do was much more ambitious structurally than what I had done before. The first book, The Little Bride, featured one protagonist, one clear arc from beginning to end. In Leaving Lucy Pear, I broadened the cast of characters, and there was certainly more complexity in terms of time, but there was still a kind of unified arc to the book. And in this book what I set out to do was thread together three very distinct narratives that were happening in completely different time periods--in fact over the course of 2,500 years. And that was a huge challenge, but I loved the work of orchestrating it. It felt musical, which is why I say orchestration, and it also felt architectural. I really enjoy structure. And I think in a lot of ways this book came to be through its structure as much as through the story. In many ways the structure and the story happened symbiotically. And playing with the structure, kind of seeing how I could move the chapters from one to the next, and the way these women's stories would overlap and eventually converge in the way that I wanted them to--that was really the great challenge of this book. I really, really enjoyed doing it and I learned a lot about my capabilities as a writer as I did it.

As I wrote it, the big fear was "Can I do this? Will I be able to pull it off?" And of course, there was a lot of work that I did in revision and rewriting to smooth out and fine tune those linkages. But it did feel, once I got going with it, like it came together pretty naturally.

How much research went into this project? Do you enjoy that part?

Yes! I did enjoy it. I do love research. There was a lot of it involved, in terms of understanding the conversations that have come before me around the Book of Esther in particular, and also in terms of getting a hold on the 1970s in Washington, D.C., and in Massachusetts (where I grew up). One of the things that surprised me is how little is actually known, both about how the Book of Esther came to be, but also what it might have been like to live in Persia in 462 B.C.E. I really enjoyed the license that that gave me to really just play. That license is part of what encouraged me to go in certain directions.

One of my favorite parts of research, always, is contacting people. Reaching out beyond the Internet and books and finding people who already know a lot about what I'm writing about, and are almost always eager and generous with their expertise. Everybody from a nonprofit international development expert who can talk about what's going on in that world today, to my rabbi, and a guy who does shellfish work in Rhode Island and knew all about which shellfish might have been eaten in the 1970s and which wouldn't. I really enjoy that part of the process. --Julia Kastner

Toward the end of my pregnancy, I picked up Great with Child (W.W. Norton, $15.95), a collection of letters from poet and author Beth Ann Fennelly (The Tilted World) to her newly pregnant friend. Full of insights large and small about what it means to shift from pregnant person to parent, this book made me realize that while I had spent much of my pregnancy reading about what to expect while pregnant, I was still entirely unsure of what to expect once I actually had a child. I loved science-minded Emily Oster's Expecting Better (Penguin Books, $17), so I quickly purchased her Cribsheet (Penguin Books, $18), which promised the same data-driven exploration of the many parenting decisions I'd face in my child's early years.

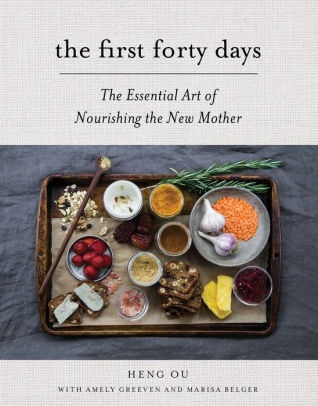

Toward the end of my pregnancy, I picked up Great with Child (W.W. Norton, $15.95), a collection of letters from poet and author Beth Ann Fennelly (The Tilted World) to her newly pregnant friend. Full of insights large and small about what it means to shift from pregnant person to parent, this book made me realize that while I had spent much of my pregnancy reading about what to expect while pregnant, I was still entirely unsure of what to expect once I actually had a child. I loved science-minded Emily Oster's Expecting Better (Penguin Books, $17), so I quickly purchased her Cribsheet (Penguin Books, $18), which promised the same data-driven exploration of the many parenting decisions I'd face in my child's early years. In my early postpartum weeks, I flipped through the pages of The First Forty Days by Heng Ou, Amely Greeven and Marisa Belger (Abrams, $29.99). Though ostensibly a cookbook (with recipes for nourishing soups, snacks and teas), it is also filled with warmth and encouragement for new mothers navigating a difficult--and significant--time of change. I explored this transition in a more analytical way with To Have and to Hold: Motherhood, Marriage, and the Modern Dilemma (Harper Wave, $26.99), in which clinical psychologist Molly Millwood dissects the frequently gender-imbalanced world of parenting.

In my early postpartum weeks, I flipped through the pages of The First Forty Days by Heng Ou, Amely Greeven and Marisa Belger (Abrams, $29.99). Though ostensibly a cookbook (with recipes for nourishing soups, snacks and teas), it is also filled with warmth and encouragement for new mothers navigating a difficult--and significant--time of change. I explored this transition in a more analytical way with To Have and to Hold: Motherhood, Marriage, and the Modern Dilemma (Harper Wave, $26.99), in which clinical psychologist Molly Millwood dissects the frequently gender-imbalanced world of parenting. In the throes of sleep deprivation, I picked up Alexis Dubief's Precious Little Sleep (Precious Little Sleep, $16.99), packed with tips for helping babies sleep (it works: I am writing this column during a solid two-hour baby nap). Up next: All Joy and No Fun (Ecco, $15.99), in which Jennifer Senior explores whether or not children make their parents happier. I'll have to get back to you on that one--naptime, it seems, is over for today. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

In the throes of sleep deprivation, I picked up Alexis Dubief's Precious Little Sleep (Precious Little Sleep, $16.99), packed with tips for helping babies sleep (it works: I am writing this column during a solid two-hour baby nap). Up next: All Joy and No Fun (Ecco, $15.99), in which Jennifer Senior explores whether or not children make their parents happier. I'll have to get back to you on that one--naptime, it seems, is over for today. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

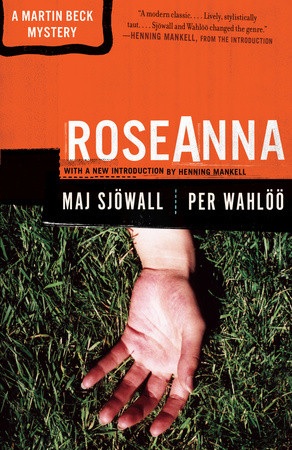

Maj Sjöwall, co-author with her partner, Per Wahlöö, of the 10 Martin Beck crime novels that are widely credited with founding Scandinavian noir, died last week at age 84. Beginning with Roseanna, first published in Sweden in 1965, the Beck series focused on Swedish police detective Martin Beck, part of the National Homicide Bureau, and the books appeared annually until The Terrorists in 1975, immediately after the death of Wahlöö at 49. The series has been honored around the world, been the basis for many TV series and feature films (including a Hollywood production of The Laughing Policeman, which also won a best novel Edgar in 1971), and was a precursor for many later masters of Scandinavian noir, including Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson.

Maj Sjöwall, co-author with her partner, Per Wahlöö, of the 10 Martin Beck crime novels that are widely credited with founding Scandinavian noir, died last week at age 84. Beginning with Roseanna, first published in Sweden in 1965, the Beck series focused on Swedish police detective Martin Beck, part of the National Homicide Bureau, and the books appeared annually until The Terrorists in 1975, immediately after the death of Wahlöö at 49. The series has been honored around the world, been the basis for many TV series and feature films (including a Hollywood production of The Laughing Policeman, which also won a best novel Edgar in 1971), and was a precursor for many later masters of Scandinavian noir, including Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson.