|

| (photo: Dorothée Brand) |

Molly Wizenberg is the author of two bestselling books, A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table and Delancey: A Man, a Woman, a Restaurant, a Marriage, and the James Beard Award-winning blog Orangette. She has written for the Washington Post, the Guardian, Saveur and Bon Appétit, and she also cohosts the podcast Spilled Milk. With chef Brandon Pettit, Wizenberg cofounded the award-winning Seattle restaurants Delancey and Essex. Her memoir The Fixed Stars is out now from Abrams Press.

My first thought when I read The Fixed Stars was that you are very brave for having written it--not just because you're so candid about your personal life but because you recount the end of your marriage to Brandon, whom readers of your previous books grew to love right along with you. Were you at all worried that your fans would be upset with you for leaving him?

I have to imagine that some of them will be. I mean, I'm as judgmental as anybody, and I know I'd have some thoughts about me, if I weren't me. I've struggled plenty with the judgments I've put on my own self--about the demise of my marriage, the decisions I made, what it means for our daughter, what it means for me as a writer. I could go on and on. I've been brutal to myself. Writing this book helped me to engage some with that inner monologue, to start to turn it into a dialogue, put it on the page and step back from it, actively interrogate my judgment and shame. They're not gone, but they're quieter. I don't expect that everyone will like what I've done and who I am--no, no. But I'm okay with myself now, more days than not.

I'm sure you've wondered this yourself: How do you think your life would have proceeded if you had never laid eyes on Nora?

I think my life would have proceeded for a while as it was, and maybe indefinitely. But someone or something else would have, at some point, woken me up like Nora did. That's what seeing her felt like, like waking up. I think it's a very human thing to have moments like that, when we find ourselves in a certain situation where we suddenly see ourselves, our potential, our lives from a different angle. I'm not talking specifically about sexuality; for some people, it's about religion, or profession, or... I don't know. Sometimes you visit a new place, and you just know you've got to live there, and you upend everything to realize a whole new version of your life. Nora was that certain situation for me.

Likewise, what do you think would have happened if you hadn't had the courage to tell Brandon about your crush?

I can't imagine not having told him. There were plenty of common silences in our marriage, I now see--things that we'd stopped trying to talk about because talking got us nowhere--but not telling him this felt impossible. The shift in my sexuality was shattering. Hiding it made me miserable, because I was hiding myself. Either I hid forever, or I told him. It didn't feel like a choice. Telling him was horrible, but it was a relief.

There's a remarkable and devastating scene in The Fixed Stars in which you tell Brandon that you want to try an open marriage. You write about all the reading you did on the subject, and you've obviously put a lot of thought into the topic. From what you've learned, do you think that it would be possible for an open marriage to endure and stay strong, or do you think that wanting an open marriage is necessarily a sign that for the person who initiates it, the marriage is irredeemably broken?

The only people who can say anything for sure about a relationship are the people in it, and I'm no (!) expert on open relationships. But from the meager amount I have learned, and from what I see in friends who successfully navigate open marriages, I can say that relationships work best when both (or all) partners are equally invested and committed. This goes for any relationship, right? Open or monogamous. That sense of being equally invested is, of course, a shifting thing; not everybody will feel the same way about it every single day. But at base, it seems to me that all partners should be similarly invested in the work of the relationship--in talking through everything, talking and talking and talking, and in listening.

Brandon and I went about opening our marriage under conditions, I think, that doomed it from the start. We weren't equally committed to it--not really. My desire propelled us, which wasn't necessarily a problem; the problem was that we didn't have equal stakes in the situation, and we continued as though we did. We learned a lot, and we talked more openly than maybe ever before, but we fell apart under the strain.

That said, we've both marveled at how that brief attempt at opening our marriage helped make our divorce less bitter and more collaborative. Because of all the emotional work we put into opening our relationship, our communication was more intentional, less reactive, than it would have been otherwise. I know that for sure.

If another author had written The Fixed Stars, what do you think you would have wished for her?

Oh, God, uh, how about universal acclaim and a castle with a moat? --Nell Beram

"Oscar is hungry. But he's eaten EVERYTHING. (Including his stable.)" What is a famished unicorn to do? In Lou Carter and Nikki Dyson's board book Oscar the Hungry Unicorn (Orchard Books, $10.99), the pink-bodied, rainbow-maned unicorn tries to fill his belly by eating a witch's house, a pirate ship, a fairy meadow, even a DJ at a cave party. Oscar, flashing his unamused and unimpressed side-eye throughout the entire book, is sure to elicit giggles from children ages zero to five.

"Oscar is hungry. But he's eaten EVERYTHING. (Including his stable.)" What is a famished unicorn to do? In Lou Carter and Nikki Dyson's board book Oscar the Hungry Unicorn (Orchard Books, $10.99), the pink-bodied, rainbow-maned unicorn tries to fill his belly by eating a witch's house, a pirate ship, a fairy meadow, even a DJ at a cave party. Oscar, flashing his unamused and unimpressed side-eye throughout the entire book, is sure to elicit giggles from children ages zero to five. A follow-up board book, Crix Sheridan's The Sasquatch and the Lumberjack: Family (little bigfoot, $12.99), isn't exactly what one might expect from the title. The Lumberjack's family meets the Sasquatch, right? Nope! The friends who met in The Sasquatch and the Lumberjack here bring their families together for group activities like motorcycling, fishing and making music. Every double-page spread features different family members in action and a single word--GRAMMIE, SISTER, MA--to identify the (lumberjack or sasquatch) family member. Colorful and full of movement, this board book is a fun introduction to simple family words for kids ages zero to three.

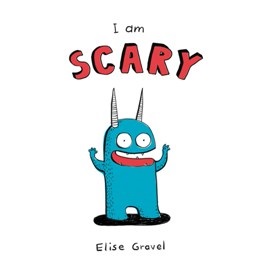

A follow-up board book, Crix Sheridan's The Sasquatch and the Lumberjack: Family (little bigfoot, $12.99), isn't exactly what one might expect from the title. The Lumberjack's family meets the Sasquatch, right? Nope! The friends who met in The Sasquatch and the Lumberjack here bring their families together for group activities like motorcycling, fishing and making music. Every double-page spread features different family members in action and a single word--GRAMMIE, SISTER, MA--to identify the (lumberjack or sasquatch) family member. Colorful and full of movement, this board book is a fun introduction to simple family words for kids ages zero to three. Pre-readers will almost certainly find Elise Gravel's big-eyed, horned monster anything but frightening. In I Am Scary (Orca, $10.95), a monster attempts to convince a child and their dog that it is very scary: "Look at my pointy TEETH! Look at my huge EYES!" The dog is alarmed but the child remains stoic, even when the monster lets out a mighty "ROAAAAR!" In fact, the child thinks the monster is cute. With a pleasant ending that caretakers are sure to love, the scary monster and the child find a better way to relate than through fear.

Pre-readers will almost certainly find Elise Gravel's big-eyed, horned monster anything but frightening. In I Am Scary (Orca, $10.95), a monster attempts to convince a child and their dog that it is very scary: "Look at my pointy TEETH! Look at my huge EYES!" The dog is alarmed but the child remains stoic, even when the monster lets out a mighty "ROAAAAR!" In fact, the child thinks the monster is cute. With a pleasant ending that caretakers are sure to love, the scary monster and the child find a better way to relate than through fear.