|

| photo: Lisa Pines |

Vijay Seshadri was born in Bangalore, India, and raised in the American Midwest. His fourth poetry collection, That Was Now, This Is Then (Graywolf Press; reviewed below), offers cerebral, wry observations on the passing of time and its impact on one's relationship to people and place, singed by the grief of loss. Seshadri's poem "The Disappearances" was published by the New Yorker after 9/11. He won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry in 2013 for 3 Sections. Seshadri is poetry editor at the Paris Review and teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. Shelf Awareness caught up with him while he was home in Brooklyn, N.Y.

You mentioned that your poems ooze out of you, rather than flow. What does that mean?

I think maybe a half-dozen times I've had a poem not just flow but flood out of me. Mostly, though, they arrive steadily but slowly, inchwise but sometimes faster. It feels like they ooze down the page because I don't write in drafts but write one line, or two lines, and then the next one or two. I have a conception in mind, but my first, fully oozed draft is very close to my final draft.

That Was Now, This Is Then is characterized by the grief expressed so powerfully in "Your Living Eyes" and "Collins Ferry Landing." Can you share the backstory to those pieces?

"Your Living Eyes" I wrote for my mother in her last months. She was dying, but was still alive when I finished the poem, and her living is what is emphasized at the poem's end. So it's not strictly speaking an elegy, and I think that's the way it should be because she was always very vibrant and full of life, replete with it.

When my father died, I wrote an elegy for him of about 20 lines, but it wasn't my idea to make this book as elegiac as it is. I wanted to write a book the underlying consideration of which was time, which this book is, but I didn't necessarily want to write a book so filled with the experience of loss. That happened because people I was very close to kept dying on me, and I was steeped throughout the writing of the poems in grief and loss, to which almost helplessly I responded with my utterances. So, for example, the initial, small elegy for my father became a big elegy, which became a representation of his inner life, of our relationship, of our experience of India, of America.

The second elegy is for the American poet Tom Lux. Were you friends?

I met Tom when I was 19. He was the leader of a very small poetry workshop that I was enrolled in in my last semester in college. He liked my work, encouraged it strongly, and I had from that moment a relationship with him that was uncanny, almost magical. Tom and I never hung out, really--we were different--and while I admired his poems tremendously, we didn't share the same aesthetic and cultural attitudes. But in the crucial moments of my life, in those times when I felt my back was to the wall, he was somehow always there to help me. He enabled my progress as a poet at every stage, even this one, because he is one of the balancing parts of the elegiac circumstances of the book. Like my parents, he was a structural element in the life I've had, which is why I needed to write something for him. His loss was unexpected for all of us who knew him, and a tremendous loss for us collectively, and for me.

Your family arrived in the U.S. in the '50s when there were few South Asian immigrants. What was it like growing up as the only brown child in the neighborhood?

Your family arrived in the U.S. in the '50s when there were few South Asian immigrants. What was it like growing up as the only brown child in the neighborhood?

Isolation was the experience of my childhood after we left India. I always think of myself as an accidental writer (I think many writers are), because that isolation was an accident of history and was also how I developed the outsider, observing consciousness that made--for me, anyway--writing inevitable. Otherwise, I think I would have become, happily, in India--hopefully, if I was capable enough--an Indian professional, an academic, a doctor, an engineer. It's a fantasy, but not an outrageous fantasy. Social and racial isolation was what schooled my imagination. (The racial issue sporadically becoming very intense and painful.). The isolation (which I think about a lot now, and for which I'm actually very grateful after all these years) was compounded both by the fact that I was chronologically isolated--I'd been skipped two grades when I was first going to school, and was also a late grower, so I was small and underdeveloped with respect to my peers--and by the fact that we were internally isolated as a family, isolated from normality (not in a traumatic way). My father was unusual cognitively, and really not capable--though he was a devoted father and husband and a good provider and a diligent scientist (he was a physical chemist)--of satisfying the received expectations of family life. A beautiful guy, but different, definitely, highly specialized, benign but nevertheless radically unlike others. We all revolved around that unlikeness. It was much more significant than the fact that we were Indians, though being strangers in a strange land didn't help.

In your everyday life, do you identify as an immigrant?

I think that's been a big change in my consciousness since 2016. Thinking of myself as a creature of the counterculture all those years (though I was one of its more sober and sedate members--a nature lover, basically), I tended to identify with a transcendental self, or, at least, a humanistic self. But the attack on immigrants in this era--poor or well-off, documented or not--has really coalesced my sense of at least my social self around the experience of migration.

It's always been a theme in my writing. Now it's a real allegiance. I identify as much with the migrant farmworker from Chiapas as I do with the graduate student in physics. Immigrants are scapegoated now, but it wasn't that way when I was growing up. Quite the opposite. The immigrant myth was one of America's durable myths then, durable to both the right and the left.

When you were 20, you ran off to the West Coast, and eventually became a salmon fisherman. How did you pivot to poetry?

I worked in the fishing industry on the Oregon coast for five years in my early and mid-20s, in the '70s into the early '80s, when there was still a robust ocean-going salmon fishery there. I gained sustenance by working on fishing boats and as a salmon buyer during silver-salmon seasons, and was actually thinking of getting a graduate education in fisheries biology.

But that narrative, rendered in that way, is probably a little misleading. I broke out of the isolation I just spoke of because of the American counterculture of the '60s and '70s. That was where I found a home, a politics, a community, a place in a social order. We were far more progressive in that counterculture than Americans are anywhere today (except, maybe, in the mind of Bernie Sanders--peace be upon him). I let myself be carried away by its currents and eddies, and they washed me up on the central Oregon coast, where the counterculture was strong.

A lot of shaggy, back-to-the-land types wound up as salmon fishermen. The fishing was an aspect of a lifestyle and a landscape I embraced. Also, I was always, from childhood on, crazy for the sea, and for sea stories. The moment I saw the Pacific I wanted to go out on it--so I stayed in Oregon, in Lincoln County. The writing was always there, though, the writing was the point--under the impetus that Tom Lux gave me when I was 19. When the counterculture finally melted away, at the beginning of the '80s, the writing was what remained.

Can you share details of the book of literary essays you are working on?

It mostly comprises the many essays I've written over the years but never collected--literary essays and essays about other arts, personal essays, introductions. I'm just putting it together, deciding what to include, etc., though I am writing a few new ones. A couple of them have to do with South Asia. I'm writing now about some time I spent in Bangladesh in 2016, and also working on an essay about Sadat Hasan Manto, the Pakistani short-story writer of the era of Partition and its aftermath. That's an intro to a selection of his stories that Archipelago Books is bringing out. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Vijay Seshadri: An Outsider's Consciousness

Michelle Obama's Becoming (Random House Audio, $45) graced the top of many a bestseller list, and for good reason: it's a smart, impassioned tale of the First Lady's life, from growing up on the South Side of Chicago to her time in the White House alongside Barack Obama. Even if you, like so many others, have already read this one, I can't recommend the audio experience enough; narrated by the author, the memoir transforms into something more like a conversation between two old friends (albeit somewhat one-sided).

Michelle Obama's Becoming (Random House Audio, $45) graced the top of many a bestseller list, and for good reason: it's a smart, impassioned tale of the First Lady's life, from growing up on the South Side of Chicago to her time in the White House alongside Barack Obama. Even if you, like so many others, have already read this one, I can't recommend the audio experience enough; narrated by the author, the memoir transforms into something more like a conversation between two old friends (albeit somewhat one-sided). Similarly, Elijah Cummings's We're Better Than This (HarperCollins Audio, $39.99) makes for excellent headphone fodder, giving more recent political events additional context. The book was published posthumously, and Laurence Fishburne's narration of it does an excellent job of capturing Cummings's passion and heart; the audio also includes clips from the late congressman's eulogies.

Similarly, Elijah Cummings's We're Better Than This (HarperCollins Audio, $39.99) makes for excellent headphone fodder, giving more recent political events additional context. The book was published posthumously, and Laurence Fishburne's narration of it does an excellent job of capturing Cummings's passion and heart; the audio also includes clips from the late congressman's eulogies. I found some comfort in Candice Millard's Destiny of the Republic (Random House Audio, $19.99, read by Paul Michael), an account of the (short) political career of James Garfield (who was nominated to the U.S. Presidency against his will, only to be shot four months after his inauguration). Though much has changed in the nearly 140 years since Garfield's assassination, it was oddly encouraging to me to realize how many times in U.S. history our democracy has felt unsustainable--and yet, here we are, ready to cast our ballots once more to decide the future of our country.

I found some comfort in Candice Millard's Destiny of the Republic (Random House Audio, $19.99, read by Paul Michael), an account of the (short) political career of James Garfield (who was nominated to the U.S. Presidency against his will, only to be shot four months after his inauguration). Though much has changed in the nearly 140 years since Garfield's assassination, it was oddly encouraging to me to realize how many times in U.S. history our democracy has felt unsustainable--and yet, here we are, ready to cast our ballots once more to decide the future of our country.

Your family arrived in the U.S. in the '50s when there were few South Asian immigrants. What was it like growing up as the only brown child in the neighborhood?

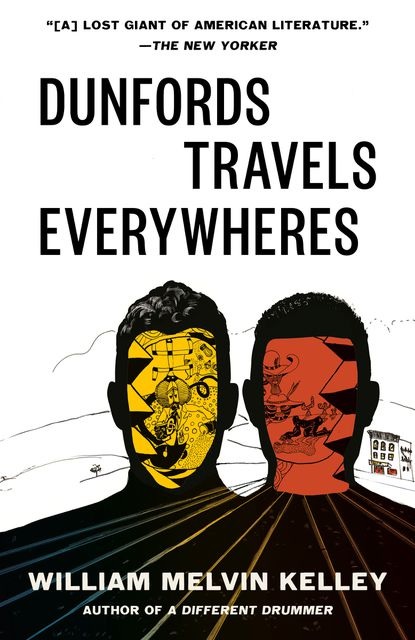

Your family arrived in the U.S. in the '50s when there were few South Asian immigrants. What was it like growing up as the only brown child in the neighborhood? William Melvin Kelley (1937-2017) was an African American novelist and short story writer who was largely unknown by modern readers until a 2018

William Melvin Kelley (1937-2017) was an African American novelist and short story writer who was largely unknown by modern readers until a 2018