|

| (photo: Lily Erlinger) |

Becky Cooper is the author of Mapping Manhattan: A Love (and Sometimes Hate) Story in Maps by 75 New Yorkers and a former New Yorker editorial staff member. Her book We Keep the Dead Close: A Murder at Harvard and a Half Century of Silence (available now from Grand Central Publishing) blends true crime and memoir to investigate the long-unsolved murder of Jane Britton and the many rumors surrounding it. In the process, Cooper delves into a range of subjects, from archeology to Harvard's insular culture and history of sexism.

In some ways, the book is as much a memoir of your long investigation as a true-crime retelling. Why did you want to lead readers through the investigation process?

I never imagined a book about Jane as a traditional true-crime story. Yes, of course, at heart it's a whodunit, and the procedural elements of the investigation are important, as is the reveal at the end. But in a lot of ways, the crime is only the motor for the story. It provides propulsion enough to dive into character studies, to contemplate the nature of knowledge creation, and to examine the ways in which the act of writing history, of conducting an investigation and of leading an archeological excavation are all ways of unearthing the material remains of the past and of constructing those remains into a story. It's a process that cannot possibly be extricated from the individuality and subjectivity of the person doing the storytelling. Therefore, even though the Jane in the book is my best effort to restore her to herself, she is still a product of my imagination. In order to be honest about the nature of her reconstruction, I needed to be a character in the book, too, to show how my own obsession with her and my own life history shaped the person I believed her to be.

After the release of the book, do you think you will move on in some ways, or are you still on the case?

There are parts of the case that I want more answers to. For instance, I'm pushing to get access to the original Massachusetts State Police crime lab files so I can get a second opinion on the evidence that led to the resolution of the case. The Massachusetts State Police rejected both my request to interview anyone at the State's DNA lab and my public records request for those lab files. Why the secrecy if they have nothing to hide?

I don't think I'll ever fully move on from this case because it's shaped the person I am, but I have to say I'm looking forward to living outside of this book. In order to write it with the kind of intensity and emotional honesty I wanted the book to have, I dissolved any boundaries I had between myself and the work. I moved away from almost all of my friends and back into my college dorm. Every time I walked through Harvard Square, I would mentally slide back to 1969 to see if I could re-create the setting as it was when Jane was walking those streets. Every time a Cambridge cop car passed by, I looked in the window to see if it was one of the officers who had investigated her case in the '90s. At some points I couldn't tell where I ended and Jane started. It was an enormous luxury and privilege to be able to devote myself so entirely to a single story, I realize, but the immersive insanity that it demanded means that I don't really know myself outside of her case. I think that suspension of self is only sustainable for so long.

Your investigation goes in so many different directions and into so many areas of study. Did you ever worry about losing the reader in the weeds, or descending too far into tangents?

I had a John McPhee quote on my wall as I was writing this book: "Every part of time touches every other part of time. You just have to find the right structure." The book definitely covers a ton of material--gender discrimination in academia, the moral muddiness of storytelling, the fight for civil rights in the '60s, the merger of Harvard and its sister school, Radcliffe, and, of course, the murder of Jane Britton. It also spans 50 years and takes readers from the crumbling mountains of northern Canada to the volcanoes of Guatemala to the hot summer afternoons in Iran. I think if I were trying to organize the material intellectually, I would have gotten completely lost. But I knew from the very beginning that I wanted the book to be organized viscerally. I'm not quite sure how to explain it. I wanted the reader to feel how I felt investigating Jane's story. And I think with that lodestar in mind, the structure just kind of unfolded organically. I needed to build and maintain an emotional propulsion in the book, and as long as I could still feel the narrative tension, I could trust that the reader would follow me into a tangent. But after a while down that tangent, I'd start to feel the tension slackening, and it'd be time for another bit of Jane's mystery to build it back up.

I also have to give a huge amount of credit to my editor at Grand Central, Maddie Caldwell, who gave me the confidence to trust myself and also reined me in when I got lost down one rabbit hole too many. (The book came in 30% longer....) She has an impeccable sense of narrative and is a puzzler at heart, and whenever I got stuck, I'd just send her a brain dump of the swirling thoughts in my mind, and she'd help me carve a way through.

Were you ever concerned that your investigation could re-traumatize the people you spoke with, or open old wounds?

Constantly. For instance, the son of one of the people in the book wrote to me begging me to reconsider what I was doing. That this awful tragedy had happened to people early in their lives and maybe, finally, after 50 years, they'd achieved some sort of peace. And here I was stirring up old feelings and hurt and guilt for the sake of what? What could I promise them? I couldn't promise them that I'd find a solution to Jane's case. Or that someone would be brought to justice. I couldn't promise them resolution or closure.

Don Mitchell--one of Jane's closest friends--and I exchanged a number of e-mails about this as I struggled with whether my investigation would bring enough good in the world to justify the pain. He assured me that while some people wanted to bury it and move on, there were also people who needed to talk about it. For them, Jane's murder was a festering wound that needed light and air. Even if I couldn't offer a name to her killer, there was healing in the process of talking about her life and her death, and of being able to see one version of Jane's story from new angles.

What do you want readers to come away from your book knowing about Jane Britton?

That Jane was funny as hell. I think her best friend, Elisabeth Handler, put it best when she said that Jane was "a mix of Dorothy Parker and Groucho Marx, except without the mustache." That Jane was young. That she was still becoming herself. That she was a great friend, and she was complicated. And that she had a gift for making people who felt out of place feel at home with her--and that's why I think this band of outsiders, even after her death, felt so committed to solving her case. --Hank Stephenson

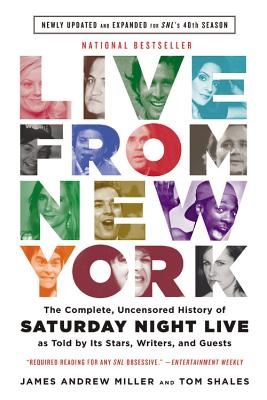

Quip aside, for decades SNL has been a cornerstone of comedy in the United States. As with many institutions, it's had hits and misses--but since 1975, the show has offered the balm of comedy. While an episode might be a salve only for a night, why not prolong the humor with stories by some of its most celebrated writers?

Quip aside, for decades SNL has been a cornerstone of comedy in the United States. As with many institutions, it's had hits and misses--but since 1975, the show has offered the balm of comedy. While an episode might be a salve only for a night, why not prolong the humor with stories by some of its most celebrated writers? Then go deep with the heavy hitters. The list of books by SNL alums is long and lustrous, but to begin, see the memoirs by some of the show's most celebrated writers. Tina Fey, the first female head writer and subsequent 30 Rock creator and star, offers up a stellar exploration of her life in and out of comedy in Bossypants (Back Bay, $16.99). Fey's "Weekend Update" co-anchor and the later star of Parks and Recreation Amy Poehler likewise delivers candor, laughs and memorable advice in her memoir, Yes Please (Dey Street, $16.99).

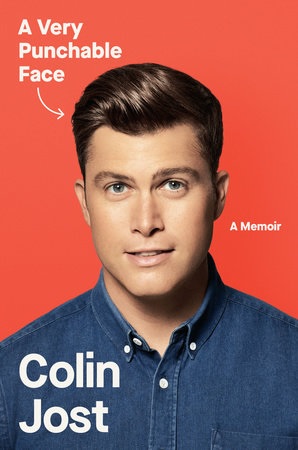

Then go deep with the heavy hitters. The list of books by SNL alums is long and lustrous, but to begin, see the memoirs by some of the show's most celebrated writers. Tina Fey, the first female head writer and subsequent 30 Rock creator and star, offers up a stellar exploration of her life in and out of comedy in Bossypants (Back Bay, $16.99). Fey's "Weekend Update" co-anchor and the later star of Parks and Recreation Amy Poehler likewise delivers candor, laughs and memorable advice in her memoir, Yes Please (Dey Street, $16.99).  Current co-head writer Colin Jost recently offered up A Very Punchable Face: A Memoir (Crown, $27). Whatever the attributes of his face, Jost's book is a comedic knockout--and all of these are reminders of the value of comedy: punchlines that help us roll with the punches, finding hope through humor in times light and dark. --Katie Weed, freelance writer and reviewer

Current co-head writer Colin Jost recently offered up A Very Punchable Face: A Memoir (Crown, $27). Whatever the attributes of his face, Jost's book is a comedic knockout--and all of these are reminders of the value of comedy: punchlines that help us roll with the punches, finding hope through humor in times light and dark. --Katie Weed, freelance writer and reviewer

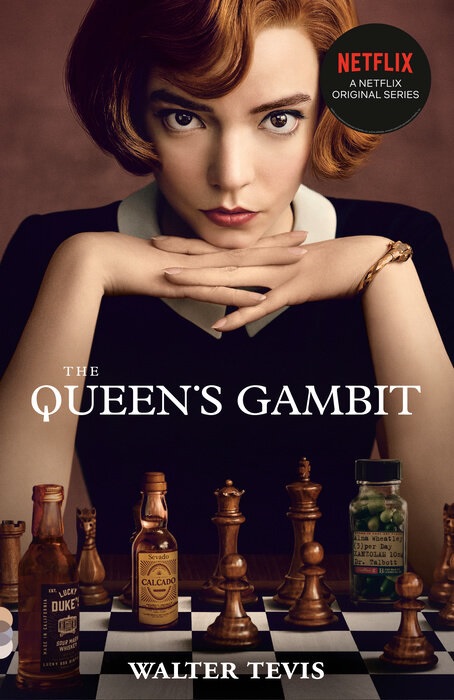

Netflix's limited series The Queen's Gambit, based on the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, follows a female chess prodigy through her early years in an orphanage to her ascension among the ranks of chess world champions in the 1950s and '60s. Beth Harmon, played by Anya Taylor-Joy (The Witch), must also contend with drug and alcohol addiction that began with tranquilizer pills dispensed to the orphanage's charges. The Queen's Gambit has received abundant critical praise and set record streaming numbers on Netflix. The series has also been favorably reviewed by real-life chess champions such as American Woman Grandmaster Jennifer Shahade, who told Vanity Fair it "completely nailed the chess accuracy."

Netflix's limited series The Queen's Gambit, based on the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, follows a female chess prodigy through her early years in an orphanage to her ascension among the ranks of chess world champions in the 1950s and '60s. Beth Harmon, played by Anya Taylor-Joy (The Witch), must also contend with drug and alcohol addiction that began with tranquilizer pills dispensed to the orphanage's charges. The Queen's Gambit has received abundant critical praise and set record streaming numbers on Netflix. The series has also been favorably reviewed by real-life chess champions such as American Woman Grandmaster Jennifer Shahade, who told Vanity Fair it "completely nailed the chess accuracy."