At its spiritual core, home body by Rupi Kaur is an impassioned embrace of earthly community, sisterhood, the right to take rest and all that makes us strong, as well as a rejection of the misogyny, abuse and the relentless pressure to be productive that make us feel less human. It arrives at a time of worldwide reckoning with unjust systems of power and the human cost of capitalism. Canadian artist Kaur--poet and performer of Punjabi-Indian descent--strategically taps into the global agitation for social change, courageously insisting on a truer, more inclusive feminism that encompasses trans women and Indigenous, Black and brown voices.

Kaur's first book of poetry, milk and honey, received rapturous worldwide attention. It was soon followed by another soaring achievement, the sun and her flowers. home body, her third collection, arrives after a three-year hiatus. Over four fearlessly stunning, vividly illustrated chapters titled "mind," "heart," "rest" and "awake," Kaur leads readers on a transformative, breathtaking journey of self-healing as she lays bare the crippling depression and "quietly loud" anxiety that held her captive after the success of the sun and her flowers. Kaur links her wounded psyche to childhood sexual abuse, the shock of adjusting to a hostile new home, watching her immigrant parents struggle, the persecution of her Punjabi-Sikh ethnic community and the pressures of our productivity-obsessed culture, all of which imprinted in her a need to question her self-worth, to push herself to the brink because she thought her brown skin meant she had to work harder than everyone else.

home body opens with Kaur loving herself out of the darkness, reuniting her mind and body after years of disconnect, with the poet's trademark black-and-white illustrations expressing her inner turmoil. In "mind" she explores where the depression came from, wondering "maybe it met me at the airport/ slid into my passport/ and remained with me/ long after we landed in/ a country that did not want us/ maybe it was on my father's face/ when he met us in baggage claim/ and i had no idea who he was." Living with depression "feels like i'm watching my life happen through a fuzzy television screen. i feel far away from the world. almost foreign in this body."

Readers who have experienced their own darkness will find Kaur at her impassioned best as she fights for survival: "i want a standing ovation/ for every person who/ wakes up and moves toward the sun/ when there is a shadow/ pulling them back on the inside." Self-hatred must also be vanquished, as her words convey with soulful simplicity: "i'm tired of being disappointed/ in the home that keeps me alive/ i'm exhausted by the energy it takes/ to hate myself - i'm putting the hate down."

It's a more forceful, resolute Kaur who emerges in "heart," declaring, "if someone doesn't have a heart/ you can't go around/ offering them yours." The poet can live without romantic love but not without female friendship. She wears her relationship scars proudly, knowing that a man can't give her anything she can't give herself: "in a world that doesn't consider/ my body to be mine/ self-pleasure is an act/ of self-preservation/ when i'm feeling disconnected/ i connect with my center/ touch by touch/ i drop back into myself/ at the orgasm." Masturbation, she says, is meditation, and kindness is at the root of all love because kindness can make you strong enough "to carry empires on your back."

Heroic aspects of the immigrant journey--moving across the world for a family's safety, back-breaking work to provide food and shelter--are poignantly recognized in a tender piece in "rest" titled "a lifetime on the road." The child in Kaur observes her father's reality--"you work until your bones become dust/ you are the only one you can count on"--in awe that her parents' sacrifices are the reason she and her siblings thrive in their new world.

The chapter "rest" is grounded by remarkable pieces on the changing nature of friendships and the "finding yourself bullsh*t" of the commercial self-improvement industry as well as the productivity anxiety that felled Kaur after the publication of the sun and her flowers: "capitalism got inside my head/ and made me think my only value/ is how much I produce/ for people to consume." The poems in "rest" offer new pathways of self-love, recognizing the soul's need for laughter and connection and an appreciation of the sheer magic of nature.

The warrior in Kaur prowls through her poetry and arrives fully present in "awake," a chapter she has described as being about resilience, change, power and the embrace of difficult things. Kaur welcomes the wisdom and freedom of thought that accompany aging, as well as the laugh lines, wrinkles and sun spots that are souvenirs of a life well lived. It is here that the author reveals ancestral scarring that will never heal, namely the Sikh genocide in 1984, when so many in her Punjabi-Sikh community were massacred by the Indian government. Her community's wounds are, in fact, the reason Kaur writes poetry.

One feels bolder and closer to the truth after reading home body, a balm for troubled times as well as a rallying cry for self-emancipation. There is no doubt that, having struggled through many layers of adversity, Kaur has emerged stronger, her narrative very much in her control: "there are days/ when the light flickers/ and then i remember/ i am the light/ i go in and/ switch it back on - power." --Shahina Piyarali

.jpg) The best cookbooks are windows into other kitchens, other cultures, other countries--an invitation to step into someone else's food traditions and, in so doing, better understand the world around us and ourselves. That's why cookbooks will forever beat any Internet recipe collection in my world; I am as hungry for the stories and the photos cookbook authors prepare as I am for the dishes they promise I can make at home.

The best cookbooks are windows into other kitchens, other cultures, other countries--an invitation to step into someone else's food traditions and, in so doing, better understand the world around us and ourselves. That's why cookbooks will forever beat any Internet recipe collection in my world; I am as hungry for the stories and the photos cookbook authors prepare as I am for the dishes they promise I can make at home. Like so many others, I currently find myself cooking more at home than ever before; amidst the long overdue racial reckoning we've seen after the murder of George Floyd, I've also been hunting for books that explore the history of race in America. These two pulls converged when I picked up Jubilee (Clarkson Potter, $35), which promises two centuries of African American cooking "that goes far beyond soul food." Author Toni Tipton-Martin delivers exactly that, drawing on decades of historical cookbooks by Black writers and chefs that represent "a gift of... culinary freedom." Alongside Tipton-Martin's recipes for gumbo and pureed parsnips and roast leg of lamb, fried chicken, lemon tea cake and sweet potato bread are snippets of these historical cookbooks, pulling recipes and notes from Black chefs dating back to the early 19th century.

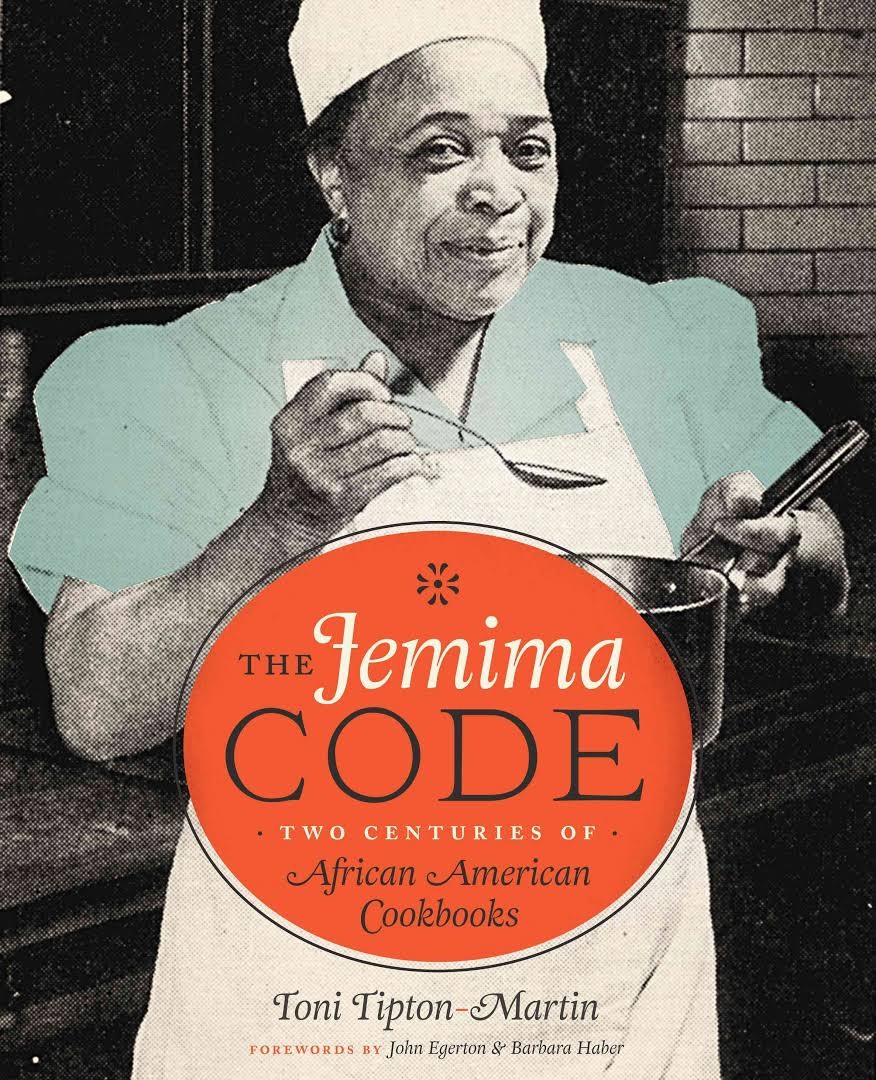

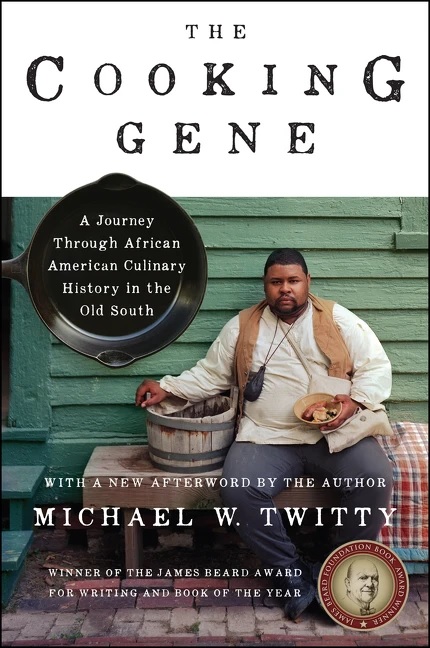

Like so many others, I currently find myself cooking more at home than ever before; amidst the long overdue racial reckoning we've seen after the murder of George Floyd, I've also been hunting for books that explore the history of race in America. These two pulls converged when I picked up Jubilee (Clarkson Potter, $35), which promises two centuries of African American cooking "that goes far beyond soul food." Author Toni Tipton-Martin delivers exactly that, drawing on decades of historical cookbooks by Black writers and chefs that represent "a gift of... culinary freedom." Alongside Tipton-Martin's recipes for gumbo and pureed parsnips and roast leg of lamb, fried chicken, lemon tea cake and sweet potato bread are snippets of these historical cookbooks, pulling recipes and notes from Black chefs dating back to the early 19th century. I quickly snagged a copy of Tipton-Martin's earlier work, The Jemima Code (University of Texas Press, $45), a history of these centuries of cookbooks, to continue my reading. I also picked up The Cooking Gene (Amistad, $28.99), in which culinary historian and historical interpreter Michael Twitty embarks on a journey to follow the paths of his ancestors across the Old South, "a place where people use food to tell themselves who they are, to tell others who they are, and to tell stories about where they've been." I cannot imagine a better way to continue my own historical education than via those very stories. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

I quickly snagged a copy of Tipton-Martin's earlier work, The Jemima Code (University of Texas Press, $45), a history of these centuries of cookbooks, to continue my reading. I also picked up The Cooking Gene (Amistad, $28.99), in which culinary historian and historical interpreter Michael Twitty embarks on a journey to follow the paths of his ancestors across the Old South, "a place where people use food to tell themselves who they are, to tell others who they are, and to tell stories about where they've been." I cannot imagine a better way to continue my own historical education than via those very stories. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm