Mystery writer Benjamin Black hates summer. "It just seems to me a boring season," he said via telephone from Ireland. "I like to be indoors. I don't like heat, I don't like seaside, and I don't like holidays. Work is more fun than fun to me, and a holiday-less year would be just fine. I like to work."

Mystery writer Benjamin Black hates summer. "It just seems to me a boring season," he said via telephone from Ireland. "I like to be indoors. I don't like heat, I don't like seaside, and I don't like holidays. Work is more fun than fun to me, and a holiday-less year would be just fine. I like to work."

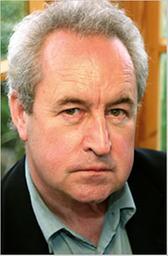

That's why Black tries to write one book each summer, which sounds like a leisurely, reasonable (almost summerlike!) schedule, until you remember that Black is actually the Booker Prize-winning novelist John Banville, who admitted, "I never stop working. If I stopped, I'd fall of the edge of the world."

When speaking with Black/Banville--or is it Banville/Black?--it's not easy to ascertain which persona is doing the talking, a dilemma complicated by the fact that the author admits that Black's protagonist Garret Quirke is of a piece with him. "I get confused constantly between Quirke and Black," said--Banville? "They're physically the same person, or at least I consider them so. In the early days of my writing the Black books, we had the idea that, because I was ambidextrous, that Black would even have a different signature than Banville. That never really flew, which is a good thing because I'm no longer ambidextrous!"

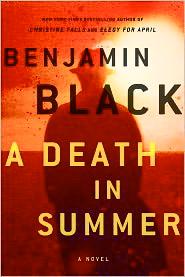

Ambidextrous or not, Banville/Black clearly has his hands in many projects. The one we're discussing currently is the latest Benjamin Black novel, A Death in Summer, just released today from Holt. In this Quirke story, the Dublin pathologist gets involved in the murder of rich newspaper tycoon Richard Jewell--and then becomes further involved with Jewell's widow, the French and elegant Francoise d'Aubigny.

Ambidextrous or not, Banville/Black clearly has his hands in many projects. The one we're discussing currently is the latest Benjamin Black novel, A Death in Summer, just released today from Holt. In this Quirke story, the Dublin pathologist gets involved in the murder of rich newspaper tycoon Richard Jewell--and then becomes further involved with Jewell's widow, the French and elegant Francoise d'Aubigny.

The genesis of the Black books came back in the early spring of 2005, when Banville went to stay with a friend in Tuscany. "I'd finished The Sea [his Booker-winning novel of 2004] the previous September. I sat in my room on that bitterly cold morning, and by lunchtime I'd written 1,500 words. It was great fun to discover that I could write fluently and swiftly. Banville, you know, scratches away. He would be glad to get 200 words written."

Black said his speed isn't because crime fiction is easy, but simply a matter of contrast. "There are ways, and there are ways, of getting down to the deeps, you see. Banville's way is to concentrate and concentrate and concentrate and go into a kind of waking sleep, a sort of controlled dreaming, while Black's way is to stay close to the surface. You can swim on the surface and see the deeps, after all. Sometimes we forget that as we walk through our lives, everything we experience is through surfaces."

For Benjamin Black, crime fiction is based not on violence, but on secrets. "When someone has a secret and keeps it, that means that it has to be buried very deep--and people with secrets betray themselves in tiny ways, through tiny movements, many of which are what we call 'superficial,' although I don't believe that that term should have such a pejorative meaning."

He gives the example of A Death in Summer's Francoise d'Aubigny, who makes a small gesture during a lunch with Quirke that tells a very big part of the story, and that involves child molestation. "You see, no one then talked about these things, and I would not give my characters the benefit of my hindsight. Of course, that's not to say people didn't abuse children in those days--they did, often using the odd phrase 'interfered with.' You could know and not know at the same time."

"We allowed it to happen. It is such an insult to the victims to say 'How could that have been going on?' " Black has harsh words for the church of his childhood. "Catholicism is so cabalistic that the poor wind up as the unelect; it's deeply hypocritical. Yet I was so deeply indoctrinated into it that I still flinch with a kind of awful respect if I see a priest coming towards me. We were exactly the same as the East Bloc countries--in place of a political party we had a clerical one."

Black noted that Ireland was behind for many, many years. "In Ireland, the 1960s didn't arrive until the 1980s. I remember coming back home from time in the United States, and it was like returning to a different world, a country that was still stuck in the 1940s. It was a monolithic society living in a kind of permafrost."

When asked about nostalgia, however, Black sighed happily. "Well, you know, horrendous systems always have an aspect of them that is good! For example, in Prague and Budapest behind the Iron Curtain, you could go to an excellent concert for about $1.50. The cultural life was superb, and valued. So, yes, I feel nostalgia for the Ireland of the past, no matter how horrible the past is. However, we've learned so much since that ghastly world passed away that any time I'm tempted by its memories I look at my children and think how much better off they are."

There is a moment in A Death in Summer when Quirke sits in Bewleys with Inspector Hatchett and reflects on its dreary yet comforting shabbiness. "Ah, it was a world," Black said with another sigh. "The thing about living in a primitive world like that is one only needs the very simple things, like a sit in a café or a love affair. Falling in love, in those days, was more of an intense experience than it is now for the very simple reason that life was so gray any emotion came like an explosion of color."

Perhaps, with that confession, it's easier to see why Benjamin Black's favorite season is autumn. There is one thing he'd like all summer-loving, seaside-holiday-taking, backyard-tan-making people to understand: "Everyone thinks that summer is about life and growth. It's not. The growth takes place in midwinter, when everything is underground. In summer, it's all quite dead."

Sadly, for Black, his next few weeks will be spent in... sunny Provence. "I can't cope with it! The sunshine confuses me." Thank goodness, for readers' sakes, he plans to stay indoors as much as possible and work on the next Garret Quirke mystery.