|

|

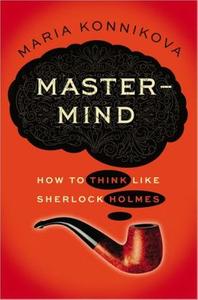

| Photo: Margaret Singer and Max Freeman | |

Psychologist, journalist and author of Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes (Viking, January 7, 2013), Maria Konnikova writes the "Literally Psyched" column for Scientific American and formerly wrote the psychology blog "Artful Choice" for Big Think. Her writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, the Paris Review, the Observer, the New Republic and the Boston Globe, among other publications. She graduated from Harvard University and is a doctoral candidate in psychology at Columbia University. She lives in New York City.

On your nightstand now:

There are actually four books on my nightstand (and a pile on the floor next to it, but who's counting); W.H. Auden's Collected Poems, which basically lives by my bed at all times. I often turn to it for inspiration when my writing is not going well. Michael Chabon's Telegraph Avenue, which I'm excited to read, at long last. (My favorite of his is The Yiddish Policemen's Union. I think he should write another noir-esque novel.) Jon Ronson's Lost at Sea. I'm loving it so far--not surprising, since he's a great writer. And Marina Vlady's Le Vol Arrêté, a memoir about the French actress's marriage to the famed Russian bard Vladimir Vysotsky.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I can't pick just one. Childhood books are a soft spot of mine, and I return to many of them over and over. But if I must narrow it down, it would be A.A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's Le Petit Prince and a book that I don't believe has ever been translated into English, Alexandra Brushtein's The Road Leads to the Horizon. It's an incredibly moving memoir of a childhood spent in pre-revolutionary Vilnius. I also must have read Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy at least five times over the course of a few years.

Your top five authors:

Again, it's tough to narrow down the field. But if I must, in no particular order: J.D. Salinger, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Vladimir Nabokov, Mikhail Bulgakov and W.H. Auden.

Book you've faked reading:

E.M. Forster's A Room with a View. Maybe I was too young for it when I tried to read it for the first--and only--time, but I got bogged down in the first chapter and have never wanted to touch it since. Perhaps I'm missing a great work of literature that I'd end up loving if I ever gathered the courage to pick it up again--but I don't know that I ever will. I feel guilty every time I see it on any "greatest book of the century" lists. And let me tell you, it appears often.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince. Too many people dismiss it as a children's book. To them I say: please, please read it as an adult. It's a masterpiece. On the other end of the spectrum, I'm quite the evangelist for Auden's collection of essays, The Dyer's Hand. I think it should be required reading for any aspiring writer.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Martin Gardner's The Annotated Alice. I didn't really need another copy of Alice in Wonderland, and it was a very expensive book, but I just couldn't resist. It's far too gorgeous. It still sits on my bookshelf, right above my desk.

Book that changed your life:

There have been too many to list. I think every great book changes your life in some way; that's why it's great. I suppose I should say Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories. And they certainly did change my life. I read them at a very impressionable age, and clearly, they stuck!

Favorite line from a book:

"Manuscripts don't burn." --from The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita. I still remember the feeling of being utterly overwhelmed when I read it for the first time. The scope of Bulgakov's imagination is astounding. It inspires you to never settle for mediocrity in writing, be it fiction or non.

Most overrated Russian author:

Leo Tolstoy. There. I've said it. Lev Grossman summed it up perfectly in his Time piece, "I Hate This Book So Much: A Meditation" when he wrote, " 'Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.' I have often maintained that this is utter bullsh**t, and I'm convinced that its bullsh**tiness would be widely recognized if it did not have the rest of Anna Karenina attached to it. But it does, and people give those lines the benefit of the doubt. Because, you know, Tolstoy." Except, I don't know, Tolstoy. I am not a fan. And he's one author whose books I have not faked reading. I've actually read them. Cover to cover. Can I also just add, as a psychologist, that he really doesn't understand human psychology?