_Chia_Messina_Color.jpeg)

|

|

| photo: Chia Messina | |

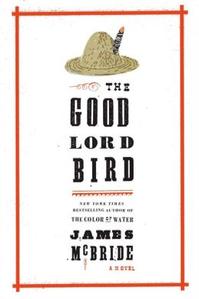

The verdict is in: James McBride's new novel, The Good Lord Bird (Riverhead), has been praised to the stars. Of course, its author should be accustomed to this. The Color of Water, McBride's 1996 memoir of being raised by his morally compelling mother, stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for years.

McBride--also a gifted saxophonist, composer and screenwriter--followed up his memoir with two powerful fictional explorations of love, possession and betrayal: Miracle at St. Anna (2002) and Song Yet Sung (2008).

An inspired blend of history and imagination, irreverence and idealism, The Good Lord Bird explores John Brown's mission to free the South's slaves, a quest that ended with the disastrous 1859 insurrection at the federal armory in Harpers Ferry and the abolitionist's hanging later that year. The novel's genius lies in its riffing, knowing narrator, Henry "Onion" Shackleford. Ten when the book begins, he undergoes an immediate sea-change when Brown rescues (or kidnaps, as Onion sees it) him, since Brown thinks him a girl.

Over the course of four years, the boy follows the abolitionist from Kansas to the Harpers Ferry standoff, with stops along the way in free and slave states and even Canada. While we witness history through Onion's eyes, the novel is far from a monologue. McBride excels at debate and drama and has created and re-created a rich cast of characters, notably a mind-blowing Frederick Douglass. But the author also gives voice to many other men and women who have been lost to history--searing individuals like the rebellious Sibonia, whose bravery dazzles Onion, and two men involved in the Underground Railway, the Coachman and the Rail Man.

How long had you been wanting to explore John Brown and how did doing so through Onion's eyes come about?

I stopped at Harpers Ferry one afternoon about 10 years ago after a trip to Maryland to research Song Yet Sung. I was fascinated. I knew there was book, but there were already at least 30 of them, and some were well done. It took a while to figure out how to explore Brown's life in a way that was fresh. I decided on an old black man reflecting on his life using the black southern vernacular because I love that voice and thought it would be effective. I grew up hearing the adults in my life, most of whom were from the South, talking that way--though some were more colorful than others.

Presenting Onion as a girl helps push the inner story--that of identity and self-realization--forward. You have to charge your outer story with inner conflict, otherwise the thing lacks muscle. Anyone can make physical things happen on the page. But the muscle comes from inside, from some kind of conflict or spark that moves people around. In this case it's identity. It's like real life, is what it is. Indeed, it is real to me, or I would not be able to lay it onto the page. The voice of a kid laying raw truth to John Brown's story seemed to be effective.

As you explored John Brown's life--and life and death in both free and slave states--how did you keep from being overwhelmed by vast number of texts and testimony?

I drown myself in them. I let the story cover me. After I'm done, I lay all the books, interviews, research, notes, etc., aside where they can be easily accessed and forget about them more or less. That absorption process is painful and I hate it. Once that's done, I sit at my desk at 5:00 every morning, hoping the characters will leap out the desk drawer and allow me to join them. Once I'm in their world, it's usually a relief from my own life.

If it is, it's unintentional. I just wanted the characters to evolve. If they don't evolve, then some connective tissue is missing somewhere and you have to go back and see where the break is. Everything must connect. I work from the premise that all characters are the same. A 1950s hillbilly gets just as thirsty and wants love just as much as a Roman emperor. How they go about fetching it is where plot and character begin the combustion process that creates story.

There's a great deal of wit in The Good Lord Bird, not least in Onion's initial collisions with the slave Bob and then with the Coachman and the Rail Man, both of whom are involved in the Underground Railway. You allow us to see and sense far more than the boy does. How do you pull off such levels of dramatic irony?

I honestly don't know. I kept it all within Onion's view, and simply let him tell it.

As in your earlier novels, women steal any number of scenes. There's Sibonia--an older woman in a slave pen in Missouri who Onion realizes plays the fool even better than him. There's Harriet Tubman. There's John Brown's daughter Annie, whom Onion falls in love with. Her kindness and decency, he realizes, come from strength and courage. Such subtle conclusions emerge naturally from the narrative, but you must be hoping that the reader will take them to heart.

I was raised by a strong woman who could make her 12 children march to their bedrooms and do their homework simply by raising an eyebrow. My mother was powerful, but she ruled from the inner emotional power, not outer physical power. In the world of fiction, where inner power is often crucial in terms of driving story and plot, strong women are essential.

Tell us about Onion's far-from-warm assessment of Frederick Douglass.

I had fun making fun of Mr. Douglass and felt a little guilty about it, because I admire him in real life. But it was just too delicious to pass up, particularly since he actually did--wisely I might add--pass up joining Brown's suicide mission at Harpers Ferry. He was just available, so I hit it. I hope I didn't get myself into too much trouble. It ought to be said that Onion pokes fun at everybody.

Onion is an excellent judge of human nature and hypocrisy, and has some trenchant things to say about abolitionists. At one Free Staters' feel-good meeting, he realizes that "there weren't hardly ever any Negroes present at most of them gatherings, and them that was there was doodied up and quiet as a mouse. It seemed to me the whole business of the Negro's life out there weren't no different than it was out west, to my mind. It was like a big, long lynching. Everybody got to make a speech about the Negro but the Negro."

The abolitionists meant well, and many were courageous and gave their lives to the cause of abolitionism. But that doesn't mean that they were absolved of the kind of racist feelings that exist in us all, black, white, and other.

The book is packed with eloquent and unforgettable unforced phrases and swings easily between comedy and deep sadness. You make it all look so effortless. Was it?

No. I sweated it. I rewrote phrases five, sometimes 10 different ways, before settling on one that had just the right amount of pop.

Onion keeps telling himself that he's waiting for the right moment to escape to freedom--"Until I figured out the lay of the land," I couldn't run off noplace."--yet he never seems to find it.

It's worth mentioning that most slaves who ran off never got far. Most got caught within a few miles from "home." Many didn't know exactly where they were running to and what they'd find when they got there. You had to be more than extremely motivated to dash for freedom. You had to be centered enough to take the loneliness, agony and poverty that awaited you once you got past the freedom line.

In your acknowledgments, you write that you are "deeply grateful to all those who, over the years, have kept the memory of John Brown alive." In Onion's telling, he's a man of infinite variety and abiding strangeness. Did your impressions of this icon change over the course of the novel?

I admire John Brown now more than I did when I first started the book. I admire his sense of moral courage, his religiosity, his sense of purpose, his lack of fear, and his overall decency. People thought he was crazy. Some of the early accounts pretty much present him that way. But he was not crazed. He was simply driven by morality and religion. A deeply flawed man with a true purpose. --Kerry Fried