|

|

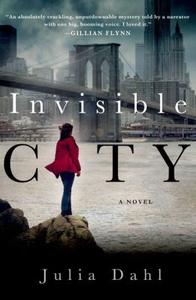

| photo: Chasi Annexy | |

Julia Dahl is a journalist and author specializing in crime and crime fiction. She has written for the New York Post and CBSNews.com, and her articles have appeared in Mental Floss, Salon and The Crime Report. Invisible City, her first novel, is the story of a young journalist in New York City reporting on the murder of a Hasidic woman in an ultra-Orthodox community in Brooklyn (our review is below).

Invisible City is your debut novel, but you have written extensively about crime as a journalist. How was writing fiction about a crime different from writing a news piece about a crime?

I think one of the things I enjoy most about writing is writing dialogue, and you don't get to do a ton of that in crime journalism. You can quote people, obviously, but when writing a piece about a crime, you weren't there. I swoop in after the crime happened and try to piece together the story from a number of sources--but I'm never really on the inside. I only know somebody from what they show me. In fiction, I get to know people from the inside, because I'm the one creating them.

What most surprised you about the novel-writing process?

How difficult it was to make the plot work. I write a lot of day stories--this is the murder, this is the charge, this is the detail we have. The length between start and finish is very short. But here, I wanted to create a plot that would keep people turning the pages, but also feel authentic. I didn't want readers to stop and think, "What? How did we get here?"

So at the beginning of the book, I knew "whodunit," and I had sense of why, but I didn't know how I would get there at all. A lot of that came in the re-writing.

Rebekah Roberts, the main character in Invisible City, works as a stringer for the New York Tribune; she is sent to various scenes across the city to collect details and call them in for another writer. Why did you decide to make Rebekah a stringer rather than a journalist?

That's just how it was, and still is as far as I know, in New York City tabloids. They're called different things--stringer, runner, reporter--but all are sent somewhere to call in information, which was really shocking to me when I first started. My first day at the New York Post, I was sent to an accident scene. I went and I interviewed people, and then I typed up a story and e-mailed it in, which shocked my editors. That was not how it worked. There were people in the office that did the writing; I did the fact-gathering. That got me thinking about ethics in journalism and how things might get printed that aren't quite accurate, because there is this chain of people involved.

So partly Rebekah works as a stringer because that's how it would happen and it felt authentic. I also hope that it pushes readers to ask questions: Is that how it really goes? Is that the right way to do this? The best way to honor the truth?

One of the other things that was important to me in Invisible City were the perils of being a young journalist without any guidance, especially in the tabloid world. Rebekah's only experience before this job is with the school paper. Now she is writing for a paper with a million readers every day, even if they do take the stories with a grain of salt or read them for entertainment. And there is a tremendous amount of power in that. Journalists and editors have a responsibility to think about the impact of what they are printing has on the people reading it. In this case, Rebekah is forced to start taking her job seriously.

How did your own religious background influence the character of Rebekah, who, like you, comes from parents from two different religions?

You write what you know, a little bit. I've spent a lot of my life actively thinking about religion and where I fit. As a child, I went to church and I went to synagogue, and I got to choose which religion was for me. So some of things I'm working out in my head as I write are about what it's like to live between two religions.

Though you are Jewish, you are not ultra-Orthodox. Why did you explore the ultra-Orthodox?

There are probably close to 200,000 ultra-Orthodox in New York City, and an even larger community outside of New York, upstate and in New Jersey. The average family size is four to five kids. And it was, especially before I moved to New York, a community I knew very little about.

Right when I had just started working for the Post, I moved into an apartment whose previous occupant had committed suicide. I found out that he was an ultra-Orthodox man who had had a family and worked as a teacher, but had been shunned because it turned out he was gay. I would get his mail, and though I never opened it, I started to build an idea of this person in my mind. And right on top of that, I was assigned to a story of an ultra-Orthodox groom who had killed himself right after his wedding.

All of that together just made me want to know more, especially because I thought how like me they are--they're Jews! But then, the thing that I value the most in my life is freedom, and it occurred to me that these are people who grow up with no freedom. I wanted to explore that.

Do you have any recommendations for other books about the ultra-Orthodox community?

The first book I read, and the one that was the most revealing for me, was called Unchosen: The Hidden Lives of Hasidic Rebels by Hella Winston. It is nonfiction, centering on a handful of people who grew up ultra-Orthodox and are attempting to leave in some way.

Speaking of further reading, I understand this won't be the last we see of Rebekah Roberts.

Soon after I finished Invisible City, I knew I had to write more about Rebekah. I've just finished the draft of second book, which is scheduled to come out next year. It takes place soon after the end of Invisible City, and Rebekah is still a reporter in New York. Rebekah's mother is a big part of the second book. I'm so happy that I get to write this character again. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm