Tim Parks is a writer and translator. He has written 17 novels, including Europa, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and, most recently, Painting Death. He is the author of several works of nonfiction, including Italian Neighbors and Italian Ways. Parks has also translated the works of Alberto Moravia, Giacomo Leopardi and Niccolò Machiavelli, among others, and is a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. He lives in Italy.

Tim Parks is a writer and translator. He has written 17 novels, including Europa, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and, most recently, Painting Death. He is the author of several works of nonfiction, including Italian Neighbors and Italian Ways. Parks has also translated the works of Alberto Moravia, Giacomo Leopardi and Niccolò Machiavelli, among others, and is a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. He lives in Italy.

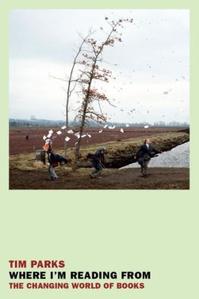

Over the past three years, Parks has written blog posts on writing, reading, translation, etc., for the NYRB online, now collected in Where I'm Reading From: The Changing World of Books (New York Review Books, May 12, 2015).

In your essays, you have challenged the glamorization of suffering and self-discovery in the traditional novel.

So much fiction does come across as self-congratulation, however subtle the process may be. And a kind of shared complacency with the reader about our supposed sensitivity. One tries to resist it, aware that even that resistance could become a motive for self-congratulation.

What do you think of the idea that the purpose of literature is to alleviate loneliness?

Please, what a sad idea.

It is. But deeply appealing to a lot of lonely people, it seems.

When you are lonely, you can of course fill some empty space with the TV, a DVD, a book or some other surrogate. But this hardly solves the problem. In David Copperfield, Dickens has David take refuge in the company of books while locked in his room by the evil Mr. Murdstone. Nevertheless David still desperately needs real company, real people. In fact the very liveliness of the literary characters he meets in those books reminds him of that. And he is aware that the uses of literature go far beyond filling his hours of punishment. Essentially, the novels he reads allow his mind to move beyond the trap in which he finds himself. He is of course delighted when he gets out of Murdstone's clutches and finds real company. Though books never stop David from making the mistakes he always does make when dealing with others.

Perhaps collectively we all have a vocation for denial. We reassure each other, thinking: if so many people believe this, why not take comfort in it? We go to churches, or read newspapers, or are members of clubs that confirm our opinions and reassure us as to the superiority of our culture, our sensibility, the talent we have, the community we belong to. A great deal of literature serves this function.

All is well, then, until something comes along to undermine our protected world. An illness, a bereavement, a betrayal, a failure. Then we can go into an even more intense form of denial--he or she is not really dead, they are in heaven, my wife may have left me for today, but she is bound to come back, etc.--or we can look for some way to come to terms with things as they are.

Giacomo Leopardi, a wonderful Italian poet of the early 19th century, makes this remark: "Works of 'literary' genius, have this intrinsic quality, that even when they capture exactly the nothingness of things, or vividly reveal and make us feel life's inevitable unhappiness, or express the most acute hopelessness... they are always a source of consolation and renewed enthusiasm."

This seems to me an interesting paradox. Sometimes it is precisely when we turn away from the protection of denial and face trouble without demands and expectations, that we find unexpected resources. I guess if we're talking about my book Teach Us to Sit Still, the story I tell there turns on the moment when I was forced to realize that there was no help or good news to be had from the folks I'd previously thought would get me through my condition, the doctors in particular.

And again when I realized that my obsession with words and books and the hope that they might constitute a sort of alternative world in which I was powerful, was actually part of the problem, not the solution. Books were doing me at least as much harm as good.

In general, when we see art, books, stories, whatever, being presented to us as a kind of panacea and somehow necessary for the survival of civilization, etc., we should always wonder whether in fact they are not part of the problem.

Which writers have offered you a more clear-eyed perspective on the world?

Perhaps more interesting is the way different thinkers or artists speak to us in different moments depending on where we're up to, what we're going through, where we came from. So I went through a phase, for example, when I was in love with Emil Cioran's writings, or Thomas Bernhard's. They offer such a withering vision of Western pieties. But these are not what I'm after now.

And then, it's not so much the aphorism or aperçu that interests me these days, but the whole way the world is presented with its seductions and conflicts. I want it to be fresh and convincing, not simply to "do literature." I've been enjoying the work of Swiss writer Peter Stamm a lot. I frequently go back to old favourites like D.H. Lawrence, Beckett. Their very restlessness is encouraging.

You've discussed how the global literary marketplace encourages universal themes and easily translated prose, and the ideal of an artist who speaks to everyone. Despite this, you have developed diverse audiences in various countries. How do you think about them when you write?

The nature of modern communications is such as to make us aware of being part of a global community as well as a local community. We are daily informed of events and attitudes all over the world. Where I live, 70% of the books on the shelves are translated. So readers and writers do not think of writing as specific to a national community. Obviously this shifts the way people write a little. They know a book could be read worldwide, not just by their fellow nationals. It also shifts the way publishers select and promote books.

As for myself, I've been in the curious situation of having my writing split in different worlds, both geographically and in terms of different reading communities and academic communities. Essayist for some, novelist for others, translator for others again. Probably if one piece of work achieved major celebrity that fragmenting would be overcome. But I actually rather like the situation.

I think of my readers in different ways, depending on whether I'm writing essays, articles, stories or novels. Certainly when writing a serious novel, one is trying to be true to the inspiration of the book, yet always conscious that it must be such that a reader can participate. In the end, though, the ways we react to the present global literary mix are, I suspect, largely unconscious. Our behaviour can shift without our knowing it. You only need to look at a video of yourself 20 years ago to see how much you've changed without really being aware of it. In that sense, there's no need for me to worry too much about the reader. On the contrary. We adapt all too easily and instinctively look for ways of pleasing. The real effort is find a way, nevertheless, to say things as they really are.--Sara Catterall